Archive for the ‘Teaching writing’ Category

Wait: Can we talk too much?

Feed your existential intelligence

I’m gearing up to teach again: freelance copywriting and social media marketing. My understanding of communication and writing and the volunteer social-media tethering we do continues to evolve. I can talk and teach and speculate about what works for communication and how to provide what a client needs. I can talk about how we need to help our clients think—that is a piece of the value-add a smart copywriter brings to a relationship. But these days I’m seeing more limits and caveats—especially in the promises inherent in social media.

These are English students and communications and journalism. Some business students. Juniors and seniors. Many are excellent writers. Many, if not most, have worked hard to develop an existential intelligence, as Howard Gardner puts it. I teach at a Christian college, and from very many discussions with students, I know they will seek a place for faith in their life and work and life-work balance. Many if not all are just as eager to make meaning as they are to find a job.

That pleases me.

That’s one of the reasons I like to teach there.

One thing I’ve learned is that work alone does not satisfy the meaning-making part of life. Nor does work itself feed the existential intelligence. Craft comes close. Especially when we grow in our craft as we seek to serve others. But work and craft and meaning-making must be purposefully-pursued.

Intentional-like.

Because if we don’t pursue them, we fall prey to entertainment. We gradually anesthetize ourselves and starve the existential intelligence with the well-deserved zone-out time in front of the big screen TV. I’m starting to wonder if some of our social media habits also starve our existential intelligence.

I wonder because I wrestle with these impulses.

No. One does not fall into meaning-making. It takes work to make meaning.

I suppose that is the work of a lifetime.

###

Dumb sketch: Kirk Livingston

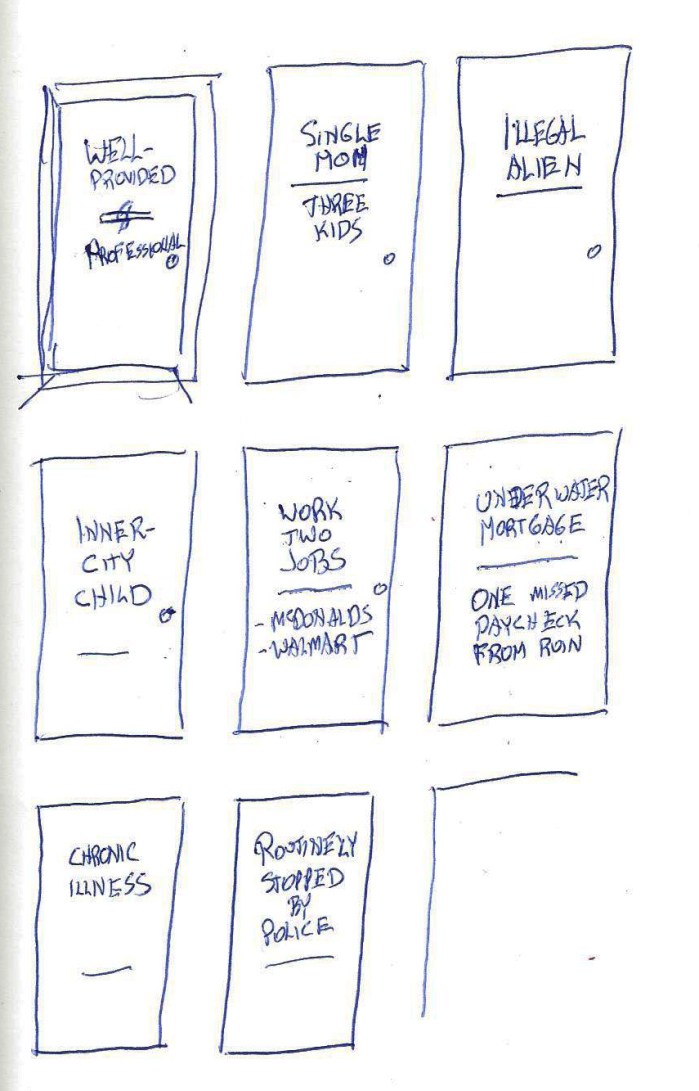

Pick a Door: Blessed are the Poor

How do you read this?

Jesus went up the mountain with his followers, as the great teachers do. His first words:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

How you hear those words depends on where you come from. The images that come to mind, the connections you make, the hope or lack of hope—much is prefigured and preloaded by the conditions you bring.

What did the original hearers hear? That is the question.

But we make a start toward answering that question by asking what door we just stepped through.

###

Dumb sketch: Kirk Livingston

Josephine Humphreys: When writing from the center of things

The world keeps aligning with what I just wrote.

Interviewer: When you’re writing, is it that you notice things more acutely?

Humphreys: Yes. You notice everything, and everything seems to be full of meaning and directly centered on the thing you’re writing about. I heard E.L. Doctorow say something like that—that when you’re writing, all experience seems to organize itself around your themes, which can give you some really strange feelings of coincidence and ESP. You start to think you’re onto the secrets of life.

–Josephine Humphreys, quote by Dannye Romine Powell, Parting the Curtains: Interviews with Southern Writers (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 1994) 192

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Pat Conroy: How to tell when the story has started

Sometimes Mr. Subconscious arrives at the work site before Mr. Conscious

I think dreams are very important. I think dream journals are important. Extremely important. I have dreamed the ends of books. When I start dreaming about the book, I know it’s now starting.

–Pat Conroy, quoted by Dannye Romine Powell, Parting the Curtains: Interviews with Southern Writers (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 1994) 51

I can’t vouch for dreams, but I cannot help but notice how Mr. Conroy’s stories seem to start without him. Writing is hard work, but there’s no denying these bits where the subconscious fills in gaps at the work site before you even arrive.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Why Academic Writing is so Boring

Insider language bores the outsider

Researchers, scientists, academicians marshal their facts to a higher standard, but with their neglect of the emotive power of language they often speak only to each other, their parochial words dropping like sand on a private desert.

–Sol Stein, Stein on Writing (NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1995) 11.

And please don’t equate “emotive” with flowery.

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston

When Truth Sounds Like a Lie

And the lie that turns out true

Let’s make up a new term: the “aspirational lie.”

The aspirational lie is that thing that falls from your mouth before you can stop it.

- It is not quite true—that’s why you almost didn’t say it.

- But it is not quite false—something about it is true. Which is why you did say it.

That happened to me when talking to a writing class of business students. My professor friend let me come in and chat about freelance copywriting. She wanted her MBA students to see some different shades to how work gets done. In the course of our discussion we talked about how one prepares to write and about how one does the work.

I told one truth that sounded like a lie.

And I told a lie that turned out to be true.

The Truth That Sounded Like a Lie

The truth that sounded like a lie was that I make a bunch of stuff up for my clients. “How so?” wondered the class. It’s like this: the writer’s work is to think forward and then tell the story of how all the parts fit together. Whether writing a white paper, a journal article, an advertising campaign or refreshing a brand, writers do what writers have always done: make stuff up. They grab bits and pieces of facts and directions and fit them into a coherent whole. As they move forward, they gradually replace false with true and so learn as they go.

That is the creative process.

You fill up your head with facts and premonitions and assumptions. Many are true, some are false. But the process itself—and the subsequent reviews reveal what it is true. Writing is very much a process of trying things on for size and then using them or discarding them. And sometimes we used facts “for position only,” as a stand-in for the real, true fact on our way to building the honest, coherent whole.

The Aspirational Lie

We also talked about backgrounds and how one prepares to write. I explained how degrees in philosophy and theology are an asset to business writing. Yes: I was making that up on the spot. But not really, because I have believed that for some time, though had never quite put it in those words. Pulling from disparate backgrounds is a way out of the narrow ruts we find ourselves in. Those divergent backgrounds help to connect the dots in new and occasionally excellent ways. Which is also why we do ourselves a favor when we break from our homogeneous clubs from time to time.

Comedy writers do this all the time. I just finished Mike Sacks excellent Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today’s Top Comedy Writers (NY: Penguin Books, 2014), and was amazed all over again at the widely different life experiences comedy writers bought to their work.

The more I’ve thought about the aspirational lie that philosophy and theology contribute to story-telling, the more convinced I am it is true. That’s because I find myself lining up facts and story bits and characters and timelines according the rhythms and disciplines I was steeped in during school. In philosophy it was the standing back and observing with a disinterested eye. In theology it was the finding and unraveling and rethreading of complicated arguments—plus a “this-is-part-of-a-much-larger-story” component.

Our studies, our reading, our life experience—all these help line up the ways we hear things and the ways we connect the dots. Our best stories are unified and coherent because of this.

###

Dumb Sketch: Kirk Livingston

English: I still believe in you.

Get in that job-machine, mister.

More dire news for university English departments: from the University of Maryland, English majors are bailing like mad. And faster and faster.

The humanities have been getting a bad rap for, oh, half a dozen decades or so, because they don’t lead directly to a slot in a job machine. And, as the thinking goes, without the job machine you fail at life. Or at least paying for life’s good things (like a huge TV and plenty of Lean Cuisine) (Or rent and clothing).

We’ve certainly seen this coming. We’ve wondered: Why go into college debt just to be a philosophy-talking barista? We’ve lamented the pitiful conditions of adjuncts. Colleges in my area cut budgets and then cut more, from fat to bone. And now wholesale amputation to accommodate the demands of producing souls for job machines.

True: English departments that focus solely on esoterics need to undergo change. I’ll argue that any academic program (or any institution, frankly) that promotes the inward-gaze as the end-all, top-function of the human condition is currently being rudely awakened.

Smart English departments are tuning in to this—just like businesses have been realizing people don’t really care about their product all that much. Even churches are starting to realize there is a world of people living and working just outside their doors—people not interested in joining the club but crazy-interested in the meaning of life. Speaking of churches, we used to call it “evangelism” when we invited others in. Business evangelists understand all too well the benefit of going where people are and adapting their product to current conditions.

But reaching out to the rest of humanity—that’s where the action is.

It’s because we’ll always need to reach out, to communicate something to someone else, that I’m optimistic about English, if not exactly English departments. Rather than an either-or approach (deep-thinking/creative expression or assembly line training), we need both-and: deep-thinking and creative expression that leads to more conscious assembly line work. And perhaps that thinking will help us move beyond assembly lines entirely.

As I prepare my next set of writing classes for college English majors, I am beefing up the entrepreneurial end. Because the way out of a soulless slot in a job machine is to invent your own job machine.

That’s something we should train writers to do. And some of those writers will be English majors.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

What Freelance Knows that You Don’t

For starters: Work is permanent while jobs come and go.

When I first considered life as a freelance copywriter, a friend said,

Welcome to the wonderful world of floating icebergs.

And it was so: projects fall off (the glacier of corporate planning) and float off to sea (so to speak, to the market) and you stand on them for a time, work on them, even as they melt under you. And then you step to the next iceberg. Or you tread water while another iceberg comes into view.

It’s a refreshing cycle—in a painful, polar-dip, take-this-horrid-medicine-it’s-good-for-you—kind of way.

I like to tell my copywriting students that the freelancer goes into it knowing this is how the game works. Then I tell them this knowing is in sharp contrast to nine-to-fiver’s who instinctually trust their jobs will remain, and are too often deeply surprised to find themselves waiting for the bus one day at 11am holding a cardboard box containing their office posters and mug.

But students typically have no mortgage or kids to feed or insurance to buy. So I’m pretty sure the comment doesn’t register until five years later, when all those conditions are true.

Recognizing the impermanence of today’s job is a great benefit, because it means one must always—always—be thinking about what’s next. The freelancer understands this in her bones. The smart nine-to-fiver rehearses this bit of knowledge every time she crosses the corporate threshold and enters the air-locked doors.

One thing that happens while I tread water is I make contact with dozens of old colleagues. I am no longer surprised by how often people change jobs, get laid off, start their own business or agency. Not to sound like an old guy, but way back when, people expected to stay at a single company for an entire career. Today I could count on one hand the number friends who have done that.

Friends often ask about work. I typically say, I’m busy and I’m looking. Always looking. In fact, this way of working has two benefits I cherish:

- Vision is no esoteric word for me. It is a hard-edge guide to what’s next. And I can never not pursue it. If I neglect to think ahead, those icebergs will float by without me ever noticing.

- The work itself become the focus. I get to burrow down into communication and copy and the telling of stories. The craft itself is a never-ending wonderland that shape-shifts as it leaps between clients and industries. The work, and the process toward the work, become the marathoner’s stroke for swimming toward the next iceberg.

In fact, faith, hope, and love remain as essential ingredients to this way of working. There is no space for taking-for-granted.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston