Archive for the ‘Ancient Text’ Category

Person of the Book or People of the Book? Love Wins by Rob Bell (Partial review)

Just how blind am I?

Recently I sat with some well-respected relatives who had devoted their lives to pursuing God. Our conversation turned to quick jibes at Rob Bell’s Love Wins. I had only vaguely heard of the book and the controversy surrounding his reading of the Bible. But knowing very little didn’t stop me from defending Mr. Bell purely based on my growing admiration for people trying to reframe stale old arguments.

My uncle said “You have to know the Book to know the Author of the book.”

I found myself in agreement and then in violent disagreement. I thought of my childhood and young adulthood growing up with the Book—that is, the Bible. We spent time in it every day. We memorized it, acted it out and generally knew it pretty well. But it wasn’t until solid conversations with others, both dead (that is, authors who left their books behind) and alive, helped me start to see the shortcuts I had taken in my own single-minded reading. That is, I started to see the blinders I wore that I didn’t even know about. I need conversation with others to help me see my blinders. I can now reassert my love for the Biblical texts, their authority in my life and the God behind those texts and Jesus the Christ who lived, died and lived—but I do so knowing faithful, admirable people can and do disagree over how some/many of those texts are read.

Can you be a person of the book without admitting others into your thought circle? There is a blindness that settles on us even more securely when we think we are just looking at the text and pulling out truth. The problem is not with the text. The problem is with our blindness, which is just another feature of the limitations of our humanness. This is not about more education. Nor is it about liberal vs. conservative. It is about seeking help to locate our blind spots. Of course, we don’t go looking for our blind spots. We go out looking for someone to tell something interesting too, and we end up finding out there is something pretty important we missed.

Also there is another piece: that of holding scripture in faith while allowing questions to sharpen and make visible some critical pieces we need to know to move forward. There is no letting go of faith here, but there is a willingness to help move closer to that truth.

I’m partway through Mr. Bell’s book and enjoy his fresh take very much. I find myself agreeing with his point that heaven is both in the future and partially present. Same with Hell. So far I don’t see anything anti-Biblical. And people from my particular tradition need only refer back to Dr. Ladd’s famous The Gospel of the Kingdom to be reminded of the now/not yet nature of Jesus’ talk about life on this planet. However, my reading of Mr. Bell’s third chapter makes me restless, because I believe there are consequences to what we say and do. I want to hear his full argument before commenting further.

My point: to be a person of the Book is to be a person of conversation.

My wife and I have been blessed by a group who will think together verbally about the Book. This group counters and challenges the inward-looking tendencies arising from my pietistic background. Certainly there is great benefit to carefully watching over our personal devotion. But real truth demands the relationships that talk.

Take-away: don’t rush to judgment in conversation.

###

Image Credit: Achille Beltrame

Try This: Wait

Waiting has a silver lining: breathing space

Years ago my wife and I met friends living in a developing country. We hung around for a few days to see what life looked like. Turns out life looked like lines. Long lines. Hours to pay an electric bill in person. Hours more for the water bill. This country was known for layer after layer of bureaucracy to handle the red tape, so the lines kept people employed even as they drove me crazy. I wondered aloud how my friend could stand it—especially knowing he tended toward a Type A personality who relished getting things done. He said, “That’s just the way it is.”

It’s hard to see any benefit in waiting. We work hard to eliminate waiting every day. I pull ahead of drivers focused on phone conversations rather than the road. I seek out the shortest line at the grocer. I click elsewhere when a web page loads too slowly. I don’t like waiting. I bet you don’t like waiting.

But my friend used his waiting time wisely. There was no plugged or unplugged then. Unlike today when most people waiting are looking into a screen, he brought a book. He prayed. He talked with people in line. My friend was a smart guy (still is) and he made a lot of connections between different parts of life. He ran a printing business, started a college and a home for families whose children were in the local hospital—even as he waited in long lines for the business of everyday.

Two recent books advocate intentional unplugging from the web, if only for short times: The Shallows by Nicholas Carr and Hamlet’s Blackberry by William Powers. Both books look at the effect of a mind crowded with stimulus and hint at what might happen with a bit of mental breathing space, which is a kind of waiting. Waiting is also a time-honored means of reflection and forward-movement in the Bible. I just finished reading the book of Psalms and saw how author after author waited for God to do something. They prayed. And they waited. And they watched (and waited).

Waiting comes with the capacity to sharpen our interest, our eyesight and our appetite. Waiting also has a purifying effect on our long-term goals. We become more realistic as we wait (or perhaps we become more insistent). But know for certain that something will change as we wait.

I’m working at waiting. Today I’ll look for an opportunity to stand around and wait. It will be hard to not pull out my phone with its checklists and documents. But waiting may allow me to connect the dots in a fresh way.

###

Photo Credit: We Love Typography

Riot, Restart and Scrubbed Minutes: The Bradlee Dean Prayer

But really…what happens when someone prays?

Last Friday Bradlee Dean gave the opening prayer at the Minnesota House. His words caused such uproar that Speaker Zeller apologized and had the prayer scrubbed from the historical records of the day. The session was restarted and Rev. Grady St. Dennis, the house chaplain gave the new prayer.

Was it a prayer Mr. Dean offered or was it a speech intended as a burr under the saddle of the gathered legislators? I don’t know all that Mr. Dean stands for, but his rhetorical mix seems misdirected. Yesterday I wrote about mixing an ancient form with something of today. In Mr. Dean’s prayer, the result from mixing an ancient form and using it as a rhetorical bully pulpit is repellent. The communication seems more speech than prayer, and seems to have been interpreted that way by the humans in attendance. And yet it is possible Mr. Dean was sincere in his conversation with God.

The notion of a public prayer is actually kind of complicated, and is perhaps a mix of forms from the beginning. One person speaks aloud. The person implores God’s attention and action. Perhaps the person seeks wisdom and mercy, or help with any of the myriad needs finite beings have. Listeners listen and agree. Or disagree. Rather than praying along and seeking the same things, the potential prayers in the House rose in disagreement shouted the guy down (figuratively, I think).

I agree with Rev. Dennis Johnson writing about the work of guest chaplains in saying “We have a special burden to include all people in our prayers….” But I’m not so sure about the last part of the quote in Lori Sturdevant’s op-ed: “…and to make the prayers nonsectarian.” Because real prayer must come from somewhere, some belief in God. It is true that belief in God need not highlight a specific brand of religion, but any prayer must be grounded in belief that God exists and hears—that alone will be offensive to some. Otherwise the prayer is just good wishes and positive vibes—not bad stuff, just not, well, real. And not that useful in seeking help from the Eternal.

King Solomon got the form right (1 Kings 8.22ff) and set a lasting example and practice. Of course, Solomon’s prayer was spoken among a set of like-minded people. So the context helps the prayer stay as a prayer: spoken to God from a bunch of people going a similar direction.

If we’re going to have prayer in the Minnesota House, there needs to be some elasticity in allowing people to pray for real. And people praying need to examine their intentions before uttering word one. But let’s continue the notion of conversing publicly with the Creator.

###

Image Credit: Buramai

Say More About That: Why one Bible writer stopped his story nearly mid-sentence and why it matters

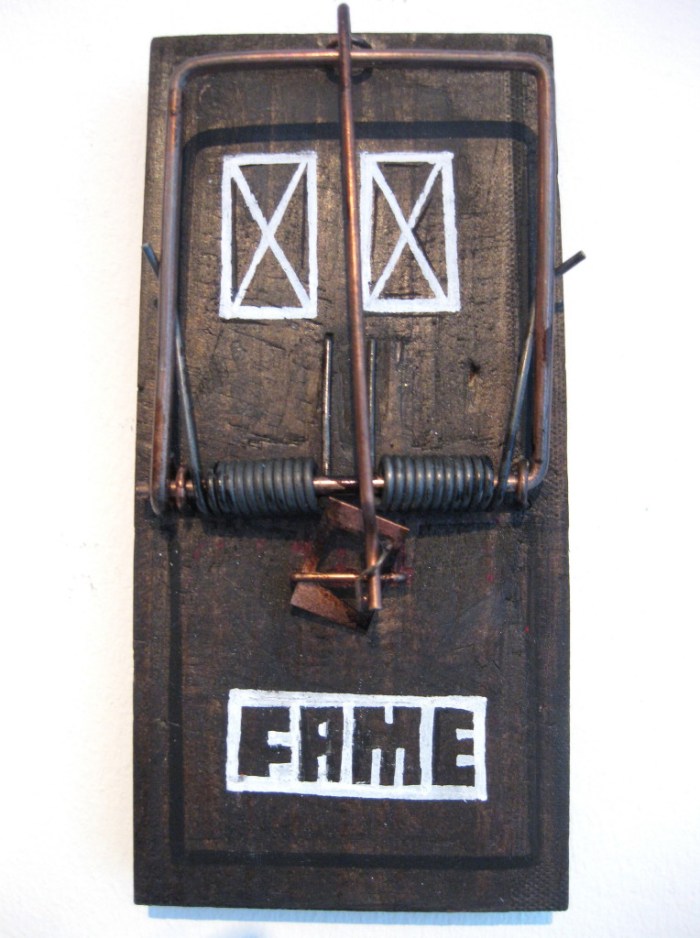

Leaving a reader with less than they want is akin to walking off stage in the middle of your performance at the height of your fame. But the technique makes the story linger all the longer.

Last week a few of us finished working our way chapter by chapter through Mark’s story about Jesus the Son of God. We found the writing idiosyncratic. Intent on capturing action, the writer jumped from episode to episode, scene to scene. The writer seemed less interested in sermons or long speeches (hey—who is?) so just left them out (when compared to the other recorders of Jesus’ life). The writer also cast Jesus’ close followers in a mostly unflattering light: not really getting what Jesus was saying. Generally intent on their own interests—so much so that Mark’s abrupt ending—leaving the followers trembling, astonished and fleeing full of fear after they encounter the empty grave—is a sure sign they never really understood the whole thing. In other words, Jesus’ followers seem like real people. No plaster saints in this story.

We argued why the writer ended so quickly. Did he hear an ice cream truck and left his manuscript and never came back? Why would he miss the important stuff like Jesus rising to heaven in the clouds (which we know from the other writers)? Some of us wished he had included more.

I think the abrupt ending was purposeful. I think he meant to leave us with questions. I think he meant for us to look back into the story and ask what it means to wait and watch. And to ask what it means to believe. The story lives on because it seems so unresolved—especially the case of this walking-talking-breathing God-man.

In the areas I work in, we continually try to build avenues to say more. More about our product. More about our ideas. More about me. We constantly work to expand the time involved for me to talk and to convince you of something. We want to gain an audience with a physician, for instance, and keep her attention until she understands the benefits of our product. But not everybody does this. Some people are smart enough to stop. Garrison Keillor may well be one of them, having recently announced he will retire in a couple years, before someone taps him on the shoulder and asks him to think about what he will do next. The writer of Mark’s Gospel was another. There were others: Plato’s Protagoras chose to end a speech in precisely the same way, which left Socrates “…a long time entranced: I still kept looking at him, expecting that he would say something, and yearning to hear it.” (Mark Denya, Tyndale Bulletin: 57 no 1 2006, p 149-150).

When is it right to leave a story unresolved?

###

A meditation on living in chesed

My friend and I both worked for a long time at a very stable medical device company in Minneapolis. We both eventually left to form our own companies. About this up and down adventure of working on your own, she liked to say “the universe will provide” because her experience was exactly that: interesting clients sought her out with interesting work, she had opportunities for growth coupled with the opportunity to learn and earn for herself and her family. I had to agree that opportunities popped up all the time—especially with the eyes-open approach of a consultant.

My friend and I both worked for a long time at a very stable medical device company in Minneapolis. We both eventually left to form our own companies. About this up and down adventure of working on your own, she liked to say “the universe will provide” because her experience was exactly that: interesting clients sought her out with interesting work, she had opportunities for growth coupled with the opportunity to learn and earn for herself and her family. I had to agree that opportunities popped up all the time—especially with the eyes-open approach of a consultant.

My question has more to do with naming the source of these opportunities. Recognizing “the universe” sounds too happenstance. Don’t get me wrong: I am all for whimsy and also a great believer in serendipity. I just want to name the source. Why? Out of joy. Out of wonder. Also because naming the source honors the source. So I credit God as the originator of opportunity.

I’m a beginner at living in dependence on chesed (God’s lovingkindness).

###

Is Death a Natural Part of Life? I say “Yes.”

Bodies are finite. Souls—not so much.

Our pastor is fond of saying “Death is not a natural part of living.” His statement is especially apropos when confronted with the death that seems so senseless and tragic: the death of a newborn child, or the death of some fresh young person moving through life powerfully with plans, ideas, momentum and devotion. Death seems so wrong. So unnatural.

I deeply lament with the parents of the child whose soul resides with God but whose body is has gone back to the earth. I pretend no knowledge of the knife blade of emotion behind such loss. I know God promises His presence—that He is as troubled and full of lament and weeping (remembering that Jesus wept at Lazarus’ death—John 11.35) as the parents. And that’s as far as I know.

My wife and I have a running controversy about whether sin brought physical death or some other kind of death. In other words, if Adam and Even didn’t disobey God in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3), would they have continued living—perhaps forever? My position is that the human body has always been finite—even in that perfect place before sin entered the world. I maintain that the very limits introduced to us by our bodies speak incessantly to the deep dependence we have on God at every turn in life.

It’s not as easy a question as it at first seems. If you think back to the Genesis texts, there’s no question that sin introduced a world of pain: literal and figurative. Just read Genesis 3 for the list of pains to expect. But at the end of Genesis 3, it is clear that men and women could no longer live in the garden because they might eat of the tree of life and so live forever (Genesis 3.22). So, banishment.

Calvinists and other reformed folk tend to think of the pre-sin version of humanity as also immortal—at least that’s how Millard Erickson sums it up in his “Christian Theology.” And if you are a fan of the Apostle Paul’s writings (as many reformers were and are), you’ll likely agree. Paul seems to often equate sin and death, for instance, in his letter to the Romans: “Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned….” (Romans 5.12) Other verses share and expand that sentiment. But did Paul mean physical death? Did God mean physical death when we warned against the eating of the fruit of that particular tree (Genesis 3.3)? Because physical death—immediate physical death—was not the result. Yes, Adam and Eve did die physically eventually. But was there a kind of death that occurred at the moment of sin?

Why Does this Matter?

This matters because of the day-to-day conversations we were designed for. The human frame was, is and has always been a fragile and needy instrument. Powerful in many respects (as any history text will attest), but profoundly weak when it comes to aging and decay. Botox and plastic surgery are of limited use. Our very weakness, on display day by day, is the thing that reminds us of God’s awesome power and keeps us coming back to talk. Moment by moment.

So—to say that death is not a natural part of life takes something away from the power and grandeur of God. It takes something away from his glory and seems to prop up the notion that we could have been able to keep on without God.

The point is our limitations constantly call us back to the original and originating conversation with our Creator. Those limitations and finitudes are built into our fabric. Mostly we seek escape from our limitations: thus Powerball, casinos and our ongoing proneness to financial scams. But what if we focused more on the conversation with the limitless One and less on fixing our limits?

What do you think?

###

Why do you call me good?

Full of capacity. Charged with purpose.

Full of capacity. Charged with purpose.

Ancient texts lead to surprising places. Jesus’ question to the rich young ruler in Mark 10.18 might have been rhetorical—not wanting to play into the man’s argument too quickly. Or it might have been a hint about the complexity of the character before the young man. It was certainly an invitation to think twice about the obvious stuff in plain view. Is cash a sign of blessing? Should I listen more closely to the important person or the stranger? Is death an end or a beginning?

###

Listen Up: #2 in the Dummy’s Guide to Conversation

The problem with listening is the other people who keep talking

You’ve opened your pie hole and made like a human: shaping experience into words that can be understood by the humans around you (though it’s still a bit fuzzy how anyone understands anything). You anticipate being stopped dead in your tracks with realization or wonder, right in the middle of a conversation.

You’ve opened your pie hole and made like a human: shaping experience into words that can be understood by the humans around you (though it’s still a bit fuzzy how anyone understands anything). You anticipate being stopped dead in your tracks with realization or wonder, right in the middle of a conversation.

But there’s a step to bridge the two: you’ve got to listen.

The traditional problem with listening is other people: they keep talking. When they are talking, you are not at the center and they keep uttering words that don’t refer to you. For instance: they rarely mention your name, which you keenly listen for. They keep talking about their own experience. Why, oh why, don’t they stop talking and ask me about me?

Let me introduce you to three friends who knew something about listening: Mortimer Adler, Alain de Botton and Jesus the Christ. I met Mortimer Adler when I read his book, “How to Read a Book.” Why read a book on how to read a book? Because of the author’s crazy fascination with understanding. He didn’t just read, he annotated, he outlined and he synthesized. He labored over passages in long conversations with the authors. Plus, he made it sound like fun (which it is!). Of course, there is not enough time to do that with every book, so Adler picked what he called the “Great Books.” His Great Books program has gone in and out of style over years, depending on your politics and your conclusions about who qualifies as worth reading.

Alain de Botton writes readable books that satisfy his curiosity and pull his readers into the vortex of questions he counts as friends. If you’ve ever wondered how electricity gets to your house or what is the process behind producing biscuits (that is, cookies) or why Proust is worth reading or why Nietzsche was not a happy-go-lucky guy, de Botton is the author you want.

Jesus the Christ knew something about listening, despite being both God and man. His human condition opened a limiting opportunity which in turn caused him to steal away for hours to converse with the God of the universe. I go into depth on this in Listentalk. But the point is that prayer, which is ultimately more about listening than talking, was a preoccupation of the man who was God.

Listening opens us to hearing—which sounds like “duh” except for when you examine your own listening practices and realize how often you are thinking of something else entirely when your spouse/child/boss/friend/neighbor appears to be talking. But to really hear, to be crazy to understand, to be curious and to be committed to connection opens us to the place where we can be stopped dead in our tracks.

###