Archive for the ‘Ancient Text’ Category

Groundswell: Your Moment Has Passed.

So 2008.

I’m done with Groundswell.

Oh, I like the book. A lot. And the argument for an empowered people (via social technologies) continues to make excellent sense. Li and Bernoff did a great service by gathering facts and stories into a rational retelling of where we are today with hearing and connecting en masse.

When I first read Groundswell, emotive moments of recognition flickered constantly. Li and Bernoff led the way in helping me understand this unfolding opportunity lodged in my computer. But those moments are not just in my computer any more. They are on my phone, in my pocket and before my eyes as I walk.

It’s the ubiquity of the opportunity that makes everything look different.

Students in my class assume forums for support will be available, they turn to product and service reviews first—why wouldn’t they? Reviews from peers have always been available. These self-proclaimed 90s kids (I guess that’s a thing) interact in most of the ways that Li and Bernoff predicted. So there are few emotive flickers from them even as I shout “Yes!” (possibly to their “Huh?” and amusement). And these students demonstrate a familiarity with technology far advanced from students even two years ago.

So…wheels turn and time goes on and books fade to triviality. I’ll suppose I’ll check out Empowered next time I teach this class. The last thing anybody needs is another old guy in their life telling how things used to be.

And this: the Groundswell moment just passed has opened on a much wider vista that seems to invite collaboration like never before. To not listen to each other is starting to feel like a cardinal sin. Not because it dishonors the human condition (which it does) but because the opportunities in working together are beginning to look massive.

###

Jesus Epiphany: “Get Your Ass Up There”

No. Literally.

Wait. How did you read that headline?

Well, it’s not a direct quote, but it’s close.

I come from a tradition where we tend to spiritualize what we read in the Bible. If the Bible talks about a woman’s wet dream (Song of Songs 5.5) we take it as some spiritual reference to her deepest emotions (Keil and Delitzsch) versus the sensual event the writer poetically described. If the writer waxes eloquent about his lover’s breasts—and the rest of her (Song of Songs 7), we look for a way the text could not possibly mean what it seems to plainly say. Because that would be too embarrassing. And this: did the writer take a break from his program of mortification of the flesh? Come, man. Get with it!

I’ve been discussing this over at The Pietist Schoolman (Sects & Sex), where the learned bloggers have schooled me on reading the passages from a “bride-mysticism” perspective

In fact, the Bible is a pretty earthy set of documents. It is full of sensual surprises right alongside descriptions and stories and accounts that soar into the heavens. That’s why it remains such interesting reading. And—you’ll likely agree—there are all sorts of ways to read things.

But in this quasi-quote from my headline, Jesus literally told his disciples to go ahead into the town and take someone’s donkey. Sort of like shoplifting only without the shop:

Now when they drew near to Jerusalem and came to Bethphage, to the Mount of Olives, then Jesus sent two disciples, saying to them,

“Go into the village in front of you, and immediately you will find a donkey tied, and a colt with her. Untie them and bring them to me. If anyone says anything to you, you shall say, ‘The Lord needs them,’ and he will send them at once.”

This took place to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet, saying,

“Say to the daughter of Zion, ‘Behold, your king is coming to you, humble, and mounted on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a beast of burden.'”

The disciples went and did as Jesus had directed them. They brought the donkey and the colt and put on them their cloaks, and he sat on them. (Matthew 21.1-7)

The Eastern Orthodox folks peg January 19 as Epiphany, which was a celebration of God becoming human. This notion of God becoming human is a central wonder to the entire faith.

Human as in earthy (born in a stable, after all), with sensual impulses and sweat and tears and stink.

But human. And God.

I find it hard to look away from the story–it beckons me to consider where it leads.

###

Image credit: DeAnn Desilets via Lenscratch

Listen Your Way Into a Larger Story

Start to stop. Stop to hear.

There’s an old story of a woman who could not get pregnant. Her rival got pregnant with unrelenting, vexing regularity. Read the story here—it’s from an ancient text many of us privilege as telling true stuff about the world.

I keep returning to this story because of what it says about how desperation drives our listening habits. The truth is we don’t listen well. Often we don’t listen until we have to: maybe we need some information and it kills us to slow long enough for the clerk/cashier/spouse to spit it out. But we need that information to get where we need to go.

But what if we made a habit of listening? Intent listening. Close listening, rather than listening only when backed into a corner. What if we eagerly sought out answers in the conversations right around us?

What if the clue to the way forward after our recent lay-off was in the conversation we’ll have at 2:30pm with an old work colleague? What if insight for a growing doubt we’ve had about our faith was just inside the threshold of a chance conversation with an old friend? What if answers to our questions were spinning around us constantly?

That sounds like magical thinking, right?

The woman in the story prayed in her vexation and angst. She prayed so hard the feeble old guy watching her thought she was drunk. The old guy was no prophet and not all that well respected, still, his words formed an answer to the woman’s long-standing question. The story goes on to tell how the answer to her question was part of a much, much larger story with questions an entire nation was asking.

Questions and conversations can be a potent mix.

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston

Lorde & The Life of Privilege

Because none of us knows everything.

Lorde’s critique of wealth (covered memorably by Puddles Pity Party) got me thinking about privilege. Her catchy pop tune about pop tunes is itself an expression of privilege. Not so much the gold teeth and Grey Goose (spendy vodka) as it is the kind of information she allows herself to dwell on: those privileged sources she and we take as true.

We all have privileged sources.

We might be a red-letter Christian or only read the Apostle Paul. We might consider sacred and true everything we hear on Fox News or NPR or read in the St. Paul Villager. We might listen more closely to a Marxist/feminist/liberation theology reading of any piece of literature. We want the commentator representing our particular bent to comment on life from the perspective of our tribe.

Humans are subjective beings and we do our best work from a perspective. We always have opinions and those opinions are based on whatever we scrape together and push under us, which is to say, we often form opinions first and then seek to support them. Every once in a while we form opinions from available evidence using solid reasoning. But that’s a lot of work.

What texts or authors or people in your life do you privilege? My two friends Rick and Jason often make remarkable book suggestions. Time and again as I’ve read their suggestions, I’ve thought: “Wow. This author is really talking to me.” My friend Russ has made prescient comments that have worked out in real life years later—so I’ve learned to not dismiss his chatter too quickly. My poor beleaguered friend Job wrote poetry possessing an uncanny ability to express my exact experience. Mrs. Kirkistan often sees things before I do. (Often? No: Usually. Typically.)

It’s not wrong to privilege our information sources—we cannot help ourselves. But it is also right to pause to examine what it is we privilege and occasionally ask why and whether we are served well by that privileged source. And perhaps to ask whether there might be other influences that can help us truth things out a bit more fully. Because (and here comes the hard part) even the John MacArthur’s of the world can have their truth sharpened by a Marxist/Feminist/Pentecostal/Whatever perspective.

Because none of us knows everything.

And I hope Lorde watches her lyrics cross the face of PuddlesPityParty. There is something revealing about the scary-tall grownup in clown costume belting out a teenager’s perspective on the world.

###

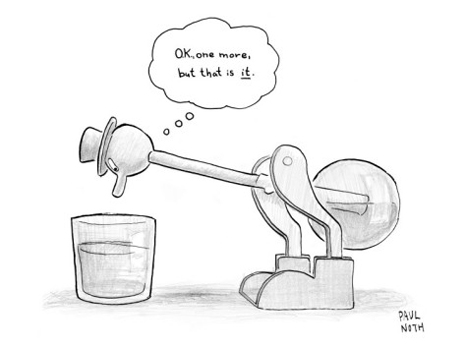

Image Credit: Paul Noth/The New Yorker via thisisn’thappiness

Prayer is just magical thinking. Right?

Asking for your own private cascade of miracles

Magical thinking is the hope that something out of nowhere will happen and change everything. When I was a kid writing stories and got stuck, it was magical thinking that rescued: suddenly the space ship landed and my main character got on and was whisked away. These were not cohesive stories. As a kid I engaged in magical thinking when I had a speech to give the next day: “Maybe the Russians will bomb us tonight and I won’t have to give that speech.”

That seemed like a fair trade-off at the time.

Some of my friends will say religionists routinely engage in magical thinking. It is this notion that someone (God) will rescue me from the pit I’ve landed in or the cul-de-sac I’ve driven into. I cannot disagree: I often have more than passing interest in rescue to come from above. Whether a work issue or a personal issue, health or wealth or life or death. Any and all of this succumbs to magical thinking. And that is what prayer is, right? A request for rescue, the more magical the better.

Magic defies logic by definition. Buying lottery tickets is magical thinking. Wearing lucky underwear on game day is magical thinking. Avoiding the professor’s eye contact is magical thinking.

But is prayer magical thinking? Sometimes, certainly: I hope I did not pray for Russian bombs to avoid my fourth grade speech on the cold war. If I did I was engaging in magical thinking.

Is prayer always magical thinking? No.

Can you bear a bit of nuance?

Say there is a God (this is not a given for some readers) and this God hears pleas for mercy. It could be that God engineers circumstance in mighty, global ways that I can neither see nor understand. As a person of faith I believe this is possible and even likely. But magical thinking asks that it happen for me and mine. Magical thinking is always about my zip code, my location, my self-interest. This is precisely where magical thinking and prayer part ways. If there is a God (and I believe there is), then prayer for magical interventions in my life will fall short. That’s because God is not just for me. God is for others too. Many others. If God is bent on reunion with people, then prayer is not answered according to magical thinking, but instead according to some other logic. The person maturing in faith starts to parse out the differences between magical thinking and honest prayer by allowing for silence. The person maturing in faith looks for this other logic.

###

Image credit: benedetto bufalino via designboom/thisisn’thappiness

Chris Armstrong Just Said Something Insightful About Work

Your Actions Keep Shouting To Me

Which is no big surprise—Dr. Armstrong, Professor of Church History at Bethel Seminary, often says insightful things.

But in the Fall 2013 issue of Bethel Magazine (if it were available online, it would be here) he pinpointed a theological missing link: that while people of faith think lots about God and Jesus the Christ and Heaven (and Hell), we have not thought much about what happens between the beginning and the end. Which also happens to be where most of us spend most of our time (that is, we’re all at various points between the beginning and the end).

Work is a key feature of what we often call “life.”

So we have Creation, Incarnation, and New Creation. But most of us are pretty fuzzy on these three key parts of the Bible narrative. And because we’re fuzzy, we super-spiritualize our faith. Faith is about the stuff we do on Sunday, at church. But darned if we knew how it’s supposed to connect with our Monday-to-Saturday life, most of which involves work. The only biblical way to get past this is to reconnect with Creation, Incarnation, and New Creation.”

(Armstrong, Chris. A Theology of Work. Bethel Magazine, Fall 2013. pp. 22-24.)

I like what Dr. Armstrong says and would encourage you to read the entire article. He draws on insights from Tim Keller’s work on work and points out, for instance, that Jesus the Christ had a first career as a contractor (building with wood and probably stone too) before he turned to the Christ business. Or this: the Christ part of his career was there all the time but latent for the first 30 years.

Allow me to adjust Dr. Armstrong’s insight with this: it’s actually our faith spokespeople who direct us toward beginning-and-end thinking. That’s where their expertise lies. You might say pastor/theologian types have (limited) authority and a free pass to talk about that stuff (especially what happens when you die). And so they do. Week after week.

But it’s up to the people living the life and doing the work to talk about what Incarnation says about, say, copywriting. Or craftsmanship. Or selling or surgery or teaching. Or digging wells (or graves). Or caring for kids or forests or the earth itself. And maybe we should look for action rather than sermons from each other, because that is how most of us talk: through the work we do.

I would go on to wager that most of us regularly draw from quite a collection of eloquent life-statements about meaning and work: both how to do it and how not to do it.

###

Image credit: Via Frank T. Zumbachs Mysterious World

(Please Write this Book) Busted, Berated & Celebrated: The Job for Anyone

Is Job the Michael Bluth of the Bible?

Now the story of a wealthy family who lost everything and the one [man] who had no choice but to, well…. It’s arrested development—with a twist: It’s Job’s tale, but with the focus shifted from his unjust suffering to a character trait everyone depended on.

He brokered peace for others.

Job had a habit of conciliating for his kids: after every round of feasting and drinking, he offered sacrifices, reasoning that just in case his kids cursed God, maybe his own intervention (which looked a lot like pleading) could help out. Just in case. This was Job’s habit.

And in the end, it worked. More on that in a moment

Would someone write this book? I want to read about how this habit of seeking help for others is more than just a pleasant idiosyncrasy of a hurting old man. Please unravel the mystery of this central piece of the story. I’d like know more about how Job’s habit of conciliation served as bookends to the entire story-with the Almighty making himself available (at least partly) because of Job’s habit. I’d like to read about how the right-sounding-but-flawed arguments delivered all the way through only reinforce how blinded we get in our self-righteousness. And how even the self-righteous need help in the end. I’d like someone to belabor the connection between what it means to care for others when you yourself are broken—wait, maybe Henri Nouwen already wrote that.

Please write Busted, Berated & Celebrated: The Job For Anyone.

I’ll read it.

I may even buy it.

###

Image credit: Wikipedia