Archive for the ‘Ancient Text’ Category

Untangling Faith and Politics

Kids: Can an Empire Pray?

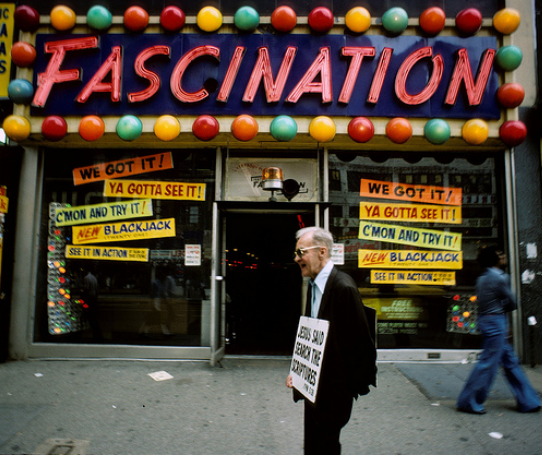

The generation before me worked hard to tie faith with politics so the two landed together like a dense brick every time one or the other was mentioned. The Moral Majority was a beginning point back in 1979 and all sorts of offshoots and sister organizations continue the cause today. The sad bit, the unanticipated piece, was that the next generation saw faith and right-leaning gibberish as the same thing. Press the vending machine button for one and you always get the other—package deal. So when the next generation rebelled (as each next generation will), they had to toss out everything.

The generation before me worked hard to tie faith with politics so the two landed together like a dense brick every time one or the other was mentioned. The Moral Majority was a beginning point back in 1979 and all sorts of offshoots and sister organizations continue the cause today. The sad bit, the unanticipated piece, was that the next generation saw faith and right-leaning gibberish as the same thing. Press the vending machine button for one and you always get the other—package deal. So when the next generation rebelled (as each next generation will), they had to toss out everything.

But start to untangle the two (faith and politics). As you do, you may remember that Christianity was a counter-culture set of priorities and commitments that offered critiques of whatever society/kingdom/regime it popped up in. And for a long time it was a faith that lived on the periphery, with Jesus as persona non grata. I’m beginning to think Christianity is most effective when living on the periphery and least effective when the state wields it as another tool for empire-building.

Of course, the truth is that faith and politics are intimately tied together. One’s faith absolutely informs one’s stance on any and every issue along with one’s voting record. But the question is what relation faith has to do with empire-building. Is faith a tool for building an empire? My reading of the Bible leaves me with a clear and emphatic: “No.”

I think of this as friends try to find ways to help their kids grow their interior lives and their lives of faith. It’s not an easy task in our culture for a few reasons. One reason is that the very notion of an interior life is drying up for many of us as silence recedes with each Facebook status check-in. But beyond that, asking questions that begin to separate faith from politics may be a way to help your kids find their way through their particular rebellion with faith thriving rather than dying.

###

Image credit: nancyishappy via 2headedsnake

The Infallibility Problem

Sacred texts don’t change so it must be our reading

When I was a kid we made fun of Roman Catholicism because they had a guy in a robe and funny hat who told everyone else what was right and wrong for all time. But what was right and wrong for all time seemed to change depending on the robed/hatted officeholder. This was hilarious to us: how could what was right become wrong and vice versa? If things were really true they would not change. Ha ha—gullible people. My people took marching orders straight from the Bible and that didn’t change.

Years later I realized nearly every one of us erects our own pope: someone who interpreted the sacred texts for us and whom we believed without question. Whomever stood behind the pulpit was a potential pope. For some it was Billy Graham or John Piper. Others looked to Carl Sagan. For a while Richard Dawkins seemed to be pope for hard-line atheists, but a new batch of atheists are sounding sympathetic to what can be learned from conversation with the faithful.

Years later I realized nearly every one of us erects our own pope: someone who interpreted the sacred texts for us and whom we believed without question. Whomever stood behind the pulpit was a potential pope. For some it was Billy Graham or John Piper. Others looked to Carl Sagan. For a while Richard Dawkins seemed to be pope for hard-line atheists, but a new batch of atheists are sounding sympathetic to what can be learned from conversation with the faithful.

Mind you, I’m not arguing there is no truth. I believe in truth and I believe it can be known by regular people. And I’m arguing for sacred texts (not against): I scour the Bible, want to hear from it and I try hard not to believe everything I think. Only because we humans have this odd predilection to read whatever we want into a text. Any text. Especially a text composed hundreds of years ago in very different cultures by wildly different authors. But what pulls me back to the Bible is the sense of hearing what God might be saying to us today, across generations and cultures and centuries. And the stories about Jesus the Christ pull me back big time—has there ever been anyone like him?

That’s why I don’t believe any one guy or gal owns it. Just like I don’t believe any single reading is the perfect reading. We’re all flawed and we all have only imperfect understanding of the truth. But when we combine our understandings of the truth, that’s when stuff starts to happen. My point is that none of us has a handle on the complete truth—and we desperately need to hear from each other.

I was reminded of this as Alan Chambers, president of Exodus International announced last week the closing of the ministry that aimed to help gay folks become straight folks. His announcement included something of an apology for the people that had been hurt through the years, including the notion that the ministry had been responsible for “years of undue suffering.” How Chambers said it was pretty interesting, at least as reported by David Crary for the Associated Press (and appearing in the StarTribune):

“I hold to a biblical view that the original intent for sexuality was designed for heterosexual marriage,” he said. “Yet I realize there are a lot of people who fall outside of that, gay and straight … It’s time to find out how we can pursue the common good.”

Two things I like about this story:

- I like hearing people of faith apologize for inflicting suffering. Mr. Chambers’ apology strikes me as bold. People will take that apology as real or lacking or simply more PR (letters to the Strib include all of the above and Salon finds the apology lacking), but it is a statement out there in the open that would most certainly produce a substantial loss of funding, were the organization to continue. I like the apology also because I’ve wondered what suffering I’ve inflicted on others because of my faith. Apologizing seems like a good communication strategy for repentant bullies like me.

- I like hearing Mr. Chambers hold to his understanding of the sacred texts. There is no getting around the fact that the texts do not point to the broad acceptance our culture seeks. And for those of us who hold those texts in high regard as words from God, our deep listening must include lots of wrestling: were they just unenlightened back then or are there theological truths we must still unearth and process together in conversation? And what do those truths look like, given the great varieties of people on the planet?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Power Pose vs. Aggressive Emptying

Sunday Story for Monday: the Counter-intuitive Ways of Sheep among Wolves

Can words spoken from a low power position influence others?

This older Harvard Business School article (Power Posing: Fake It Until You Make It) describes how simply snapping your body into a power pose can have a physiologic effect. Read about the small study (N=42) by Cuddy, Carney and Yap here. Striking a pose for two-minutes stimulated higher levels of testosterone (hormone linked to dominance) and lower levels of cortisol (so-called stress hormone) in the study group. People literally felt more powerful and less stressed after their pose.

Every human dreams of more power. More power translates to being respected. Maybe power looks like speaking and being heard as one with authority. And perhaps with more power we’ll become benevolent despots bestowing good unto others as we stride through our own personal kingdoms.

The promise of more power is intimately tied with many of our messages about leadership development. Industries and institutions will always buy more technique about leadership development because, well, who doesn’t want to be perceived as capable and full of power?

In stark contrast, there’s an old story about how Jesus saw the authorities of his day use their power for their own aggrandizement while offering little help to the harassed and helpless crowds. So he organized and commissioned his own set of spiritual paramedics to go to the harassed and helpless.

Just before these spiritual paramedics hit the streets to proclaim and heal and cast out demons and raise the dead, Jesus told them how little personal power they would have. They would not be received well. Despite their hopeful message they would be beaten and tortured, and hauled in front of councils, governors and kings.

And that’s how it played out: powerful messages in powerless packaging.

Was there something in the powerless packaging that actually helped people hear the message? Powerful words and actions delivered by powerless, peripheral people could not be enforced or made into law. There was little outside incentive to listen. And yet what they said and did endures today, these many centuries later.

Tell me again: why is it we all seek power so eagerly?

When Constantine turned Christianity into the law of the land, the message lost much saltiness. Does my lust for power come from wanting to help people or just wanting them to play my game by my rules? Are there any truths I have to deliver today that might be helped by “aggressively empty” versus a pose of power?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

What, exactly, about the light?

Brillianted and Shadowed and Beyonded

What about the light turned mundane joyous?

Dorian asked. Great question.

On May 23 at 7:32am I widened a set of blinds in a way I typically don’t. My office was brillianted (please, ma’am, can that be a verb?) in a light I don’t often witness. After our long winter and so many dark mornings, this unfettered, energetic beam lit tired old spaces. Intense oranges resulted. Jaunty slants of shadow led to spot lit scraps of yesterday’s thought pinned to the wall—the ordinary jetsam of my process.

This May light a minor miracle revealing what I had forgotten.

It was the visual parallel of smelling fresh bread or brewing coffee—arming my lazy brain and fortifying it for that day’s work.

That new old light still reminds me of the old gospel story where the man now walking was never the only paralyzed man in attendance. Shining light can make a person dance.

###

Image credit: mirrormaskcamera via 2headedsnake

The Riddle of the Difficult Person

Run Away Vs. Run Toward

My instinct says run. Or at least avoid. Either way, get out of the line of fire.

And my instinctual response to the difficult client/boss/colleague/family member is completely wrong. Entirely and utterly misguided. That is because avoiding the difficult person gives them a kind of power over you that will come to no good. Not only is avoiding the difficult person impossible (for such people will always and forever show up in your life), it is not smart. There is something you are to learn from this difficult person. Some hard life-lesson.

One of the ancients spoke of iron sharpening iron and his words describe precisely the mechanism of action with the difficult person. Something about this person grates on us: she is too bossy. He is too passive. He only thinks of himself. Everyone knows she is mentally unstable.

To be present with the difficult person we must step out of our usual ways and do something different. Perhaps we start by biting back the caustic retort. Maybe we stand up and against the sudden wrath which is our difficult person’s typical communication pattern. Perhaps we need to force a clear “Yes” or “No” from the mouth of our difficult person. Perhaps we offer the solution to them in the form of a question so they can take credit for the idea.

We all have these people in our lives and there are as many different types as shades on the color wheel. That’s because our interactions are dynamic and each of us constantly responds to a bevy of moment-by-moment inputs and impulses.

We all have these people in our lives and there are as many different types as shades on the color wheel. That’s because our interactions are dynamic and each of us constantly responds to a bevy of moment-by-moment inputs and impulses.

So take heart: there is some opportunity to move forward in the difficult encounters that hang like a cloud around this person. Learning to say no. Learning to clarify. Learning to probe for what is bothering this person. Learning to probe and learn from our own responses. These are all life lessons that sometimes come at a dear price.

And there is more: there may be something deeper going on. When you choose to show up with the difficult person, it’s with your physical and mental presence. And your emotional presence—all these can help inform your response to the difficult person. And one more: your spiritual presence. No, I’m getting all religious here, but wouldn’t you agree that some of the people you meet during the day need far more than you could ever provide?

Sometimes running toward the difficult person looks like an internal prayer offered to God on behalf of a conversation that is about to happen.

###

Image credit: red-lipstick via 2headedsnake, Wikipedia

Philosophers Make Uncomfortable Pastors

Sermons built on questions only inflame the faithful

It’s the philosopher’s job to ask uncomfortable questions. They don’t take ideology as a given. They question ideology—that is forever the philosophical task. Some philosophers reading this would say “Yes, and what do you mean by ‘pastor’ and who/what is ‘God’”? That’s fair and a reasonable line of questioning. Certainly worth examining.

It’s the philosopher’s job to ask uncomfortable questions. They don’t take ideology as a given. They question ideology—that is forever the philosophical task. Some philosophers reading this would say “Yes, and what do you mean by ‘pastor’ and who/what is ‘God’”? That’s fair and a reasonable line of questioning. Certainly worth examining.

But say a philosopher has satisfied herself there is a God. And say that philosopher has a commitment to the God revealed in the Bible (yes there are such people). Can she pastor others? Can he serve as a shepherd? Can she speak sermons that have questions rather than answers?

No. At least not to our typical congregations. People come to church for comfort and to be told they are going the right direction. To offer the food of questions is to deny parishioners the happy holy feeling they paid for when the offering plate passed by.

But honestly, can a pastor be anything less than a philosopher? Because the claims of Jesus (to start there, for instance) are so wildly outlandish as to call into question the threads of daily existence. For instance, this notion of turning the other cheek to the one who just slapped you—it’s completely nutty stuff. Unless it is actually meant to be worked out in daily life. Unless it says something crazy deep about each and every interaction we have. To treat Jesus’ words as ideology only—as some exalted religious state—and to not examine them further in the crucible of daily life is step forward with 75% of your brain shut off.

And that’s no good. That’s no way to live.

It’s also true that most philosophers don’t abide the preacher’s art of packaging things in tidy simple packages that are easily understood. Questions don’t often fit those boxes: they bump against corners and lids with their labored back story and brief histories of how others have asked them. That’s tedious stuff that rarely fits into three alliterative points.

Which is not to say philosophers should not pay attention to packing their thoughts so they become mind-ready. They should and many do. But philosophers mostly cannot escape the orbit of the questions themselves.

I think philosophers don’t make good pastors. But I hope to stumble on such a being at some point in my existence.

###

Image credit: 4tones via 2headedsnake

When Did I Learn People Don’t Matter?

Jesus and Mr. Levinas show a different way

I’m scanning back through my childhood to remember when it was I picked up this notion that people don’t matter. I cannot blame my parents or my early religious communities or the packs of feral boys I ran with. It wasn’t at Riley Elementary School, and certainly not from my first grade teacher Mrs. Buck.

But somewhere along the line I got in my mind that I could turn and walk away from people and relationships. Somewhere I learned a kind of arrogance that made me think I alone knew what was right, had all the answers, knew the best way. This thinking meant I didn’t need to listen, though sometimes I could condescend to pretend interest. Looking back, it’s hard to imagine why I ever thought this way.

Maybe it’s our get-the-checklist-done culture. Maybe it was the arrogance of my 18-year-old self who knew everything without the slightest inkling how wide the world was. And yet that arrogance persists in the odd niche and behind unopened doors in my life.

I’ve taken to dwelling with a dead philosopher whose writing remains quite lively to me. Emmanuel Levinas is not the model of clarity, but even in his glorious obscurity he says things that make me pause. I recently asked [the long dead] Mr. Levinas to comment on that inaugural address Jesus delivered up on the mountaintop. Mr. Levinas, not exactly a Jesus-follower though he respected the Torah, has a lot to say about the intrinsic worth of people and even hints that others have authority over us in the sense that we owe them attention. From the get-go.

I started to find a lot of agreement between Mr. Levinas and Jesus. Mr. Levinas insisted on the priority that the Other holds in our lives. Jesus reframed the Old Testament law by putting treatment of people up near the top of what it means to be right with God. For instance: Jesus talked about forgiving, even loving, as the alternative to getting even. This has huge implications. Not because we have so many enemies, but because we naturally harbor and nourish each slight done to us.

My philosopher friends from the Analytic tradition (most of the philosophers in this country, judging by the academic programs available), get all twitchy when I mention the Continental tradition of philosophy, which is where Mr. Levinas hangs out. Analytics have a lot of suspicion about how Continentals assemble their arguments. And lots of smart people think Mr. Levinas goes too far. But I think not. In fact there is something in Mr. Levinas that brings Jesus’ inaugural speech back in focus for me.

Mr. Levinas is helping me reconsider the notion that Jesus was not speaking hyperbole. That he really wanted his listeners to give priority to others—even those who had hurt them. This is revolutionary stuff and not at all easy. And it must be understood in the larger context of Jesus’ inaugural address and the way he walked it out later.

Still.

Giving people priority in our lives is neither a recipe for madness nor sycophancy. In fact it may be at the heart of our humaneness and our mental health.

###

Image credit: John Kenn via 2headedsnake

Why Teach?

Teaching is an epistemological playground

Yesterday I posted under the title “The unbearable sadness of adjunct.” I hope you read on to see it was a larger discussion about the price anyone pays to live a thoughtful life. I tried to show the realities of teaching as an adjunct (often agreeing with Burnt-Out Adjunct), especially noting the counterintuitive reality that some advanced degrees still offer jobs that force you to choose between buying groceries or paying the mortgage.

Yesterday I posted under the title “The unbearable sadness of adjunct.” I hope you read on to see it was a larger discussion about the price anyone pays to live a thoughtful life. I tried to show the realities of teaching as an adjunct (often agreeing with Burnt-Out Adjunct), especially noting the counterintuitive reality that some advanced degrees still offer jobs that force you to choose between buying groceries or paying the mortgage.

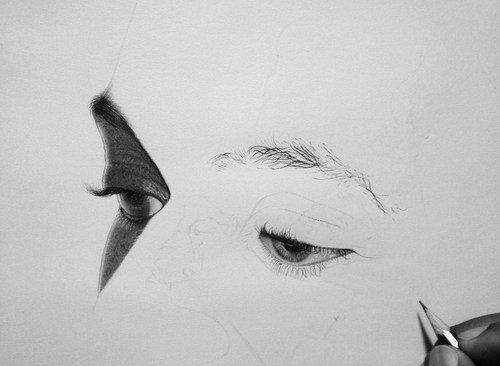

But there are also good reasons to teach. If you can afford it (counting the work you do to earn a living and/or opportunity costs of time spent on teaching), it is work that is full of meaning. Here are a few reasons I continue to seek opportunities to teach as an adjunct:

- There is a thrilling something about developing a coherent idea and presenting it to a class of students. Even more thrilling, when you see that they see the utility of the idea.

- Class times often become incredible conversations. Not always, but often poignant things get said that help move my thinking (and humanity) to a new level

- To teach is to learn. And learning is great fun. There’s nothing like trying to explain something to someone else to show how little you really know. As I explain, synapses fire and brand new stuff happens in my brainpan. Teaching is a kind of epistemological playground.

- Students are amazing. At the college I teach, I remain deeply impressed by the devotion and care and passion many (not all) bring to the work. I often encounter excellent writers and I want more than anything to help those people move forward.

- Faith and work belong together. Every year I teach I see this more clearly and I labor over (and yes, I pray about) how to explain the connection. My own work as a copywriter highlights and dovetails into this connection. I am very pleased to bring with me ancient texts that explicate the meaning of work and life.

Naturally, there is more to say about this. What would you add?

###

Image credit: Kelvin Okafor via 2headedsnake