Archive for the ‘Ancient Text’ Category

There Is No Litmus Test for President

There is only conviction and thinking and prayer and conversation.

And even that conversation will vary within your community.

And even that conversation will vary within your community.

I’m reminded of the paradoxes of the old culture wars. A couple decades ago when politics were just as heated and dialogue just as rare, Mrs. Kirkistan and I lived in a rough section of South Minneapolis. People of faith in our community—I’ll call them Christians—routinely voted “for” Democrats. Given the particular demographic quirks of the area, it was easy to understand why those candidates did better. For a variety of reasons (economic, housing, vision, spiritual) we ended up moving miles away. We eventually found ourselves at a large suburban church where the assumption was that everyone voted “for” Republicans. Mind you, much of this was never said aloud. It was all just assumed.

After all, Republicans were anti-abortion and that’s where God hangs out—right?

After all, Democrats cared for the poor and that’s where God hangs out—right?

The danger of litmus-test thinking is that it promises some clear, unassailable answer: the candidate is this or the candidate isn’t this. Case closed.

I argue that leadership is and always has been about more than one thing. There is no litmus test because the human condition is complex and society and culture are exponentially complex. And while I’m certain God is all about creating life, the Creator is also bent on sustaining life, so listening to the poor, the widow and the orphan take up a lot of column-inches in our common, ancient text. But even those are not litmus-like tests, because which party will actually do those things best?

I’m hoping the faith communities around the country will have conversations that help their members vote not according to some mandate from a culture-wars war-room, but instead according their growing convictions from dealing with texts, from conversation and from prayer.

It’s time the church led by being counter-culture.

###

Image via thisisn’thappiness

Malala Got Shot for Just Saying

What We Say Matters

In his fascinating After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (NY: Oxford University Press, 1975), George Steiner speculated on the origins of languages. At first it seems like a no-brainer: given all the people and geographies and histories and wars and all that has happened over time, sure, we have a whole lot of languages. But Steiner goes all systematic through the known number of languages over the course of history and asks the rather obvious question: Why? Given that human bodies all work roughly the same way, and that we ingest roughly the same foods the world over, and the we all need air and water and sunshine and coffee (ahem)…why is it again we don’t all speak the same language? It’s a great question and his book is a readable and erudite discussion on the topic. I’m only a few chapters in, but two things stand out:

- Steiner believes all of communication is translation. Whether inside a language or between languages, we are constantly translating and decoding words and meaning. I think he is right about that: there is no end to trying to understand each other. Even couples married for decades need to translate the words spoken by the spouse to understand what it is they really meant. And then to sort out what they should do about it.

- Steiner speculated on a “proto-language,” a sort of first language from which all other languages descended. Steiner called it Ur-Sprache (p.58) and likened it to the language of Eden. A supremely powerful language that when spoken, made stuff happen. One need only think of a couple old Bible stories to get the sense of the promise of this old language: God speaking stuff into existence and Adam naming all the animals (with no committees second-guessing his naming choices).

But…alas…this language is no more.

Or is it?

Maybe we still see hints of Ur-Sprache every day, when we say things and our saying seems to make it so. Saying a thought aloud has a kind of generative effect. Not always. And with more or less effect. But still—stuff happens when we talk.

Maybe this is why people in the U.S. hold so tightly to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. And why people all over the world agree that freedom of speech is a human right (except for despots, when speech calls attention to their efforts to rape and pillage their people). And maybe that’s why we feel almost personally violated by the Taliban in Pakistan singling out and shooting a teenager (Malala Yousafzai) for speaking her mind. It is beyond repulsive. Beyond degenerate.

###

Image Credits: Vladimir Kush, AFP/Getty Images

What Question Consumes Your Church?

Not so easy to answer for most of us.

Church is not a place of questions. It is a place of sameness and routine, where old stories—even ancient stories—are retold. We go to church to be reassured, right? Reassured we are forgiven, for instance. Reassured that I am personally going the right direction, and perhaps even welcoming that kick-in-the-pants reminder of how I veered off-course—yet again. Reassured there is a God. And that God has something to say.

Church is not a place of questions. It is a place of sameness and routine, where old stories—even ancient stories—are retold. We go to church to be reassured, right? Reassured we are forgiven, for instance. Reassured that I am personally going the right direction, and perhaps even welcoming that kick-in-the-pants reminder of how I veered off-course—yet again. Reassured there is a God. And that God has something to say.

No, church today is not a place of questions. It is a place of answers.

It was not always so.

I’ve been reading through an ancient text that documents the questions the early church was trying to sort out. One primary question was, “What is this thing?” A question even more visceral was surely muttered silently, “What the hell is going on here?” And after that, questions tumbled forth from any and every quarter:

- “How can this possibly work?”

- “How could I be friends with you?”

- “Is this belief so dangerous that I am hunted for it?”

- “Why are you sharing your fortune with me?”

- “Am I ready to die for this?”

Questions everywhere because what was happening was outside the control or vision of one or any individual. Questions because they were watching God do stuff. Extraordinary stuff.

Today we have it figured out. Programs and formulas and seminars and best practices—just like with any industry. We’ve got experts who know stuff.

But every once in a while, I see something in a church and say under my breath, “What the…? How can that possible work?”

###

Image credit: Alleanna Harris via 2headedsnake

Coursera Learnings: The Close Reading

Word by word, pay attention to the text

It’s actually what I did yesterday with my visceral response to the Dassault Systemes commercial from Casual Films which appears to have touched a nerve.

It’s actually what I did yesterday with my visceral response to the Dassault Systemes commercial from Casual Films which appears to have touched a nerve.

Not so long ago I wrote about the Modern Poetry class I’m attending with ~30,000 new friends. We’re watching Professor Al Filreis and a team of dedicated UPenn student TAs react to and discuss Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, William Carlos Williams, Allen Ginsberg and others. The class involves a fair amount of dissecting meanings and is lots of fun. And now we are grading each other’s close readings of a Dickinson text. The Coursera machinery for dealing with a massive online open course is startlingly easy to use and even (sort of) personal. Kudos to Professor Al Filreis and team!

For me this was to be a year off from grading college essays, but these essays are different. People from all over the globe are struggling to sort out what the assigned Dickinson poem means. Some—like me—have never worked this closely with poems. Many of us read our own meanings into the text—often this is linked with a lack of close attention to the words. Even word by word: the close reading demands the individual words add up to something. To gloss over the words is the thing that allows me to pack in my own meanings. I’ve noticed this tendency for years reading ancient texts with small groups: the farther we get from the words on the page, the easier it is to attach our pet peeves to the author’s supposed/assumed point. But the words themselves lead into or out of meaning and belief.

I was struck by one of our course readings: this poem by Cid Corman:

Cid Corman, “It isnt for want”

Naturally, there is lots to say as you go word by dash by word. But one thing—from the perspective of conversation—Corman focused on how we know something about ourselves as we stand together in conversation.

###

Image Credit: Zoltron via thisisnthappiness

Say What You Will: Dummy’s Guide to Conversation #10

How to Not Feel Bad About Voicing Your Opinion

I grew up wanting to not disrupt people. Sadly, I remain a people-pleaser.

I grew up wanting to not disrupt people. Sadly, I remain a people-pleaser.

I’m working on it. (so back off.) (darnit.)

But I’m learning lately that every voice really does matter—no matter what condescending tone your client or boss or the VP takes in today’s conversation. Even when she sighs and says “We’ve been over this,” know that if it bugs you, you need to bring it up. And the know-it-all in Purchasing doesn’t really know it all—he just sounds that way. So raise your point. If what you hear doesn’t sit well, say so and tell why. Reject verbal manipulation and say what you will. Be civil. But say it.

That inveterate letter-writer said to speak truth in love, and he was right (again). Each of us hears only what we want to hear most of the time. And it only gets worse over the years as our blinders sit more firmly over our eyes and ears. We don’t see or hear what we don’t know. We’re not even looking for it. But we need to hear it, and sometimes we desperately need to hear the big obvious thing everyone is trying hard to not say. Our words are most effective when they carry with them true care for another person. “True care” as opposed to the catty smites that characterize so many of our public forums.

Say it because your conversation partner will get over it. Or not. It is true that sometimes our words can end friendships—but that is less likely when our words also communicate care.

And beyond our need to hear from outside ourselves, a lot of critical human work gets done within the moving parts of a conversation: affirmation, understanding, self-understanding, mutual-understanding, reframing a situation, brand new ways of looking at things. That list is long.

But none of that happens if we don’t say what we are thinking. So stop worrying about disrupting the day of the self-important windbag. Much bigger things are at stake.

###

Image Credit: Eric Breitenbach via Lenscratch

This Cheers Me: Rejected Muslim Supporters Invite St. Anthony to Dinner

Not so many weeks back the St. Anthony Village community (not far from the Livingston Communication Tower) held a meeting to consider whether an Islamic center could be built in the community. The meeting got heated, lots of ugly stuff was said aloud, and the proposal was rejected. Whether or not the council acted on anti-Muslim bias (the U.S. Department of Justice is investigating), fear of the unknown seems to have ruled the roost.

People will say what they will say—our country protects that right—which is a fantastic freedom. But our country (city and suburb, mind you) is composed of lots of different folks: religion, color, body shape, languages, musical tastes. A crazy diversity which becomes more interesting every single day. Christians (whether in name only or fully functional) don’t own the place and cannot dictate the rules.

I’m cheered because in this case the stranger has acted on the words that would/should/could motivate the Jesus-follower: they are throwing a dinner (an iftar) Thursday night at the St. Anthony Community Center.

What an interesting time to be alive.

###

Relevance is Dead. Long Live Relevance.

Future church isn’t like present church: connect four dots

We’re relating differently these days. I’m not talking just about Facebook and Twitter and/or any other rising social media. We’re relating differently because our expectations are changing—partly due to our experience of being heard (which does relate to social media). This post is aimed at the church, but much of it could apply to any organization. Some parts are unique to the church.

Here are four points to consider as you think about how organizations may connect in the future. Apply yourself to three bits of reading and one bit of listening. It’s all interesting/amusing/amazing. Then tell me: how do you see the church changing?

Dot 1: Jeff Jarvis & the Death of Content

Jeff Jarvis was invited to speak to a group of professional speakers. He spoke about how content is dead and how the speakers should really be hearing from the audience and piecing together brand new things.

I suggested — and demonstrated — that speakers would do well to have conversations with the people in the room and not just lecture them. I said I’ve learned as a speaker that there is an opportunity to become both a catalyst and a platform for sharing.

His talk did not go over well with the professional speakers and there was plenty of harrumphing. Read his article here. But the take-away was the opportunity for speakers (and leaders) to be both “catalyst and platform for sharing” versus pouring content from a podium.

Dot 2: Jonathan Martin & the Decline of the Church Industry

Over at Big Picture Leadership there is a lengthy quote from Jonathan Martin who has suddenly seen that he is not at the center of things. He laments that the Spirit has passed him and Piper and Driscoll and CT and all the other usual suspects in favor of the rush of new Jesus-followers in developing nations. Read the excerpt here. Read the whole thing here.

I like this guy’s approach. I think he nailed it. But I disagree that the Spirit has moved on to other countries and peoples. I think the Spirit is alive and well and deeply embedded in God’s people—wherever they are—just where the Spirit will always be as long as people profess faith in Jesus the Christ. But what Mr. Martin observed is simply the decline of church as an industry in the U.S.

To that I would add: and not a moment too soon.

It was never sustainable, anyway: all the inward-focused authority generated by books and CDs and conferences and leadership gurus and models and formulas. Why did we think that God worked through all that? Oh. That’s right. Because the authors and conference leaders told us so. Here’s my favorite take-away from Mr. Martin:

We enjoyed our time in the mainstream well enough to forget that the move of God always comes from the margins . . .

But what if Mr. Martin is even more accurate than he knew or believed? What if the locus of authority is shifting from controlling authorities to the people in the pew who refuse to spectate? What if people really started taking seriously the notion that they should bring their gifts and voices directly into the ritual gatherings and far beyond—sort of like that inveterate scribbler Paul wrote?

Dot 3: Apophenia and Participatory Culture

At Apophenia they are asking questions (fitting!) in preparation for a book on participatory culture. What is participatory culture? I’m new to the phrase too, but danah boyd cites several characteristics of such a culture:

- With relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

- With strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with others

- With some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

- Where members believe that their contributions matter

- Where members feel some degree of social connection with one another (at the least they care what other people think about what they have created)

I very much like this notion and phrase because that is the culture I most want to belong to. I spend my days thinking about communication in industry. I think the church holds the key to the most invigorating participatory culture possible. I believe the future of the church will be a participatory culture speaking directly to all culture rather than focusing inward to build a religion industry.

Dot 4: Reggie Watts: Sing the Milieu

Watch this guy produce his own content (sounds)—even as he grabs content (sounds and ideas) from the environment—to make something new. It reminds of Jeff Jarvis’ note that content is not king, and how he challenged a group of professional speakers to listen to their audience. It also hints at a jazz-like participation with the audience and the larger environment.

Perhaps one way to connect the dots is to say that the top-down approach to relevance is dead or dying. The top-down approach has long been a battle cry of the church-industry: let’s give the people what they ask for, but we’ll mix in the stuff we think they need, like giving a pill to a dog by mixing it in her food. Maybe what we’re seeing now is a new mix: content relevant from the bottom up because people are listening in a new way. More precisely, they are listening for the good stuff planted there by the Spirit of God.

And please hear: this is not either-or. It is both-and.

The church can lead the way in this. Not the church as an industry, but the church made of people. But will leaders have courage to listen to individuals? Or will leaders circle the wagons?

How do you connect the dots?

###

Image credit: Howard Penton via OBI Scrapbook Blog

Pray Like You Talk. Talk Like You Pray.

How to be.

Back when I was newish to this notion of pursuing reunion with the Creator, I began to wonder about prayer. Was it just a kind of thick wishing; full of detail and electric longing, uttered into the silence? The practices of prayer remain mysterious to this day, but way back then my buddy said something I’ve never forgotten:

Back when I was newish to this notion of pursuing reunion with the Creator, I began to wonder about prayer. Was it just a kind of thick wishing; full of detail and electric longing, uttered into the silence? The practices of prayer remain mysterious to this day, but way back then my buddy said something I’ve never forgotten:

“Look. Just pray like you talk. Simple stuff. Forget the impressive words. Just talk.”

That proved useful. It still makes sense to me today.

Prayer is an articulated event. A speech-act that causes things to happen out in the world—though not exactly the way you might hope. This is what people who pray believe (people like me): that by talking to the One who controls everything, laying out the case, and leaving it there, stuff starts to happen. Of course, dictation and demands are fruitless. So are bargains. Prayer doesn’t work that way—it’s not exactly a reciprocal relationship.

But what if my friend’s advice worked the other way too: what if that easy conversation full of detail and electric longing was a part of our daily, hum-drum human conversations? So rather than utter desire into silence we uttered it into relationship? That does not sound like wishing into the silence. People would be listening—the very people right around you. They would hear. And sympathize. Or challenge. You’d get known. Your peaks and valleys would be known. There would be no hiding. If our talk were like our prayer, there would be a measure of freedom, and a whole lot of assumptions about the level of interest in our conversation partner.

No. Now I see that would never work.

But. Wait—that characteristic of being known is a peak human experience. What if we were designed for that very thing?

That would be something.

###

Image Credit: Kris Graves via Lenscratch

In the presence of evil

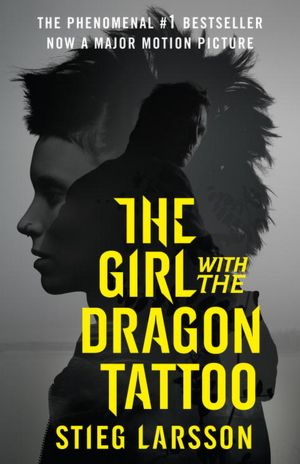

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Hit Me Hard

I just finished Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and I’m not sure I have the courage to watch the movie. The violence is sadistic. And the violent intent boils up from unvarnished evil. But because I am a sappy reader, I get even more queasy about well-drawn characters I’ve grown to care for who keep walking into ever more desperate situations.

In the Wikipedia entry for Mr. Larsson, there is a claim that everything that happened in the book—all that brutality—actually happened in Sweden at one time or another. Somehow Mr. Larsson had seen something in his growing up in rural Sweden that made him both fearful and a lifelong activist against far-right extremists. He responded to this evil with these “fictionalized portraits” of the people and culture he knew. Of course no culture has cornered the market on brutality, sadism and ever-deepening horror: Just last weekend as we sat on the Memorial Union Terrace at UW Madison on Saturday evening, I found myself pointing out the smokestack of the asylum on the other side of Lake Mendota where Wisconsin’s own Ed Gein was housed—he of the lampshades crafted from human skin.

But why spend time reading about great evil? And why be entertained by such things? It’s hardly uplifting, though the reason we watch shocking horror stuff is often for the very purpose of getting our blood moving.

And yet it is partly uplifting for a couple reasons: because the evil is overcome in the end (Oops. Did I spoil the book for you?). And because the evil is overcome at least in part by shining a light. By letting others see what was going on. My vision of the activity of solid reporting was raised by this bit of fiction, and it made me grateful for the journalists I read every day.

One part of the story speaks to the continuing human need to interact. I say that because the more hidden our behaviors became the more deplorable they can become. It seems that Blomkvist (Larsson’s main character) reason for living was to expose what was hidden. Another part of the story hints that it’s not so far-fetched to look deep inside ourselves and locate an equally limitless capacity for evil.

I cannot help but be reminded of that old dead letter writer who wrote that “everything exposed by the light become visible—and everything that is illuminated becomes a light.”

Mr. Larsson’s book illuminated things for me.

###