Archive for the ‘art and work’ Category

How do your tools shape you and your customer?

We work with tools. Tools work back.

It is not precisely true that our tools train us. More to the point: our tools sometimes wake dormant skills. Our tools help us exercise muscles we’ve not used so much: for instance, my running shoes help me exercise a different set of muscle than my bicycle typically requires. I know this because I have different pains after using each. An axe requires differing coordination skills than a hammer, which is also different from a ratchet.

Current social media tools exercise our collaboration muscles. From Facebook and Twitter we began to see that collaborating is fun. And we start to look forward to working together. It now feels good use those muscles and skills. It feels productive.

So when we require each other to sit silently in a long meeting, well, that doesn’t feel so good anymore. Or when we tell our employees or our congregation to go do this thing without asking for their input and experience—that just won’t fly anymore. And if we expect our customers to buy whatever we sell with no questions, well, that model has been dead for some time (the cult of Apple comes to mind as one exception).

David Straus in his practical and interesting How to Make Collaboration Work (San Francisco: Berrett-Kohler Publishers, 2002) rightly labels this a matter of human dignity:

People who are directly affected by an issue deserve to be able to express their opinions about it and have a hand in formulating a solution. (46)

How are the current tools changing the expectations of your client, customer or congregation?

###

Image Credit: Inkdrips via thisisnthappiness

Wes Anderson and the Intrigue of Low Affect

After recently watching Moonrise Kingdom we’re on a jag of Wes Anderson films at the Livingston Communication Tower (high over Saint Paul). Anderson brings a recognizable color palette and camera work to each piece of communication. He also brings a tone that is memorable for comedy touched by a bit of failure. Or failure touched by recognition and agreement.

Even his short persuasive tools earn my rapt attention: this American Express commercial is a masterpiece of jumbled information layered into less than straightforward answers, all of which makes no sense until suddenly it does. This Softbank commercial with Brad Pitt showcases Anderson’s playful direction that rolls with the action even as it creates its own. There is something lighthearted about the commercials while his films often circle a darker place.

The other night we watched Rushmore. In the middle of the movie, Mrs. Kirkistan wondered aloud how dark it would get. But by the end…well, I won’t spoil it, except to say it ends well, which is not a surprise. But along the way it is the understated communication that perpetuates a kind of unflappable honesty that runs through the characters and scripting. Bill Murray wears the honesty particularly well.

Color, emotional affect and carefully framed shots all figure highly in Anderson’s work. Each feels like a mini-play, like we could be watching it on a stage rather than on a small frame on the wall. Or maybe like we’re seeing an old, forgotten toy spin again, but this toy has a few barbs attached. The Darjeeling Limited and Fantastic Mr. Fox certainly have this feel.

NY Times columnist Rick Lyman in his 2003 book Watching Movies, sat down with a number of movie-types to see the films that influenced their art and careers. Wes Anderson was one of these types, but in 2003 more “up-and-coming” than established. Lyman asked Anderson why he chose to watch Francois Truffaut’s Small Change.

Mr. Anderson, it turns out, is the sort of person who tells you—a little sheepishly—that he has no answer to something, and then spends the next two and a half hours giving you one.

Wes Anderson may be something like his movies. But then I would expect art to have a relationship with its creator.

###

Being Present is Hard Work

Just Don’t be Boring

I know this from teaching college students. Some students are right there with you (I love these people!). I see others fade into and out of our discussion while some simply park their carcass in a chair as their mind plays on a sandy beach in South America. I don’t blame them. Helping any audience be present is a challenge for every communicator. It’s a challenge I try to take seriously in teaching, writing and face-to-face conversation. A creative director I worked with would always say, “just don’t be boring.” He was right. No speaker or conversation partner has a right to squander someone else’s attention.

I know this from teaching college students. Some students are right there with you (I love these people!). I see others fade into and out of our discussion while some simply park their carcass in a chair as their mind plays on a sandy beach in South America. I don’t blame them. Helping any audience be present is a challenge for every communicator. It’s a challenge I try to take seriously in teaching, writing and face-to-face conversation. A creative director I worked with would always say, “just don’t be boring.” He was right. No speaker or conversation partner has a right to squander someone else’s attention.

I know being present is hard from my own experience as well. Paying attention to someone requires a lot of energy. Maybe introversion/extroversion has something to do with it. Maybe not: extroverts have an especially hard time listening because they really, really want to interrupt and say their spiel.

Over the weekend I talked with a physician who works really hard at being present with each patient. Her day is spent in 15-30 minutes intervals of intense listening followed by repeating what she heard, followed by diagnosis mixed with more listening and more response. It’s easy to see why it takes all her energy.

Rereading Robert Sokolwski’s Introduction to Phenomenology, I ran across this quote:

All experience involves a blend of presence and absence, and in some cases drawing our attention to this mix can be philosophically illuminating. (18)

The physician worked hard at being present with her patients precisely because the words uttered by patient after patient were only one piece of the puzzle. She was also analyzing what wasn’t being said, what the patient was trying not to say, as well as analyzing physical appearance and the way the patient holds him or herself. Same stuff we all pay attention to, but the physician needs to draw concrete conclusions or at least educated guesses that could lead to a course of action.

Being present is a gift we give to each other.

###

Image credit: Paul C. Burns via thisisn’thappiness

Garry Trudeau Writes Essays. His Essays Look Like Comics.

Garry Trudeau Writes Essays That Get Read.

Garry Trudeau has been writing essays for as long as I’ve been reading comics. His essays get read because they are peopled with, well people. Characters. Hand-drawn characters. We call his essays a comic strip. Comic strips are easy to read. Essays are hard to read and boring—unless they are comic strips.

Garry Trudeau has been writing essays for as long as I’ve been reading comics. His essays get read because they are peopled with, well people. Characters. Hand-drawn characters. We call his essays a comic strip. Comic strips are easy to read. Essays are hard to read and boring—unless they are comic strips.

His current essays on for-profit colleges make me want to run out and check facts, though the tone resonates with what I’ve seen. But Trudeau is a master at breaking facts (and innuendo) into panel-sized chunks. How I could do that with my essays is worth thinking about.

###

Via Slate

Pleasant Propaganda: The Museum of Russian Art

Plan on seeing the exhibit of Soviet Paintings (From Thaw to Meltdown: Soviet Paintings of the 1950s-1980s) at The Museum of Russian Art in South Minneapolis before it closes shop later this month.

The paintings on the top two floors start with unbridled propaganda, depicting solid workers grinning about their jobs in the steel mills, factories and collectivist farms. The strong women and robust men in their industrial settings are both beautiful and horrifying at the same time, when you realize some of the workers were more likely emaciated prisoners from the nearby prison (“Beautifying Saransk” by Alexander A. Mukhin). But the exhibit takes you beyond the grand hyperbole to show how the artists worked within the political boundaries even as they let bits of reality in. By the time you get to the back of the top floor, you are seeing more realistic depictions, including the unsettling working conditions in steel mills.

It’s worth walking downstairs to see photos of actual workers, families and daily life in the Soviet Union: gritty and sober images in black and white. If you grew up during the Cold War, these are the images you remember.

And then it’s worth considering how images shape our lives. The propaganda paintings are easily recognized and dismissed—though many seem stunning today. The photos in the lower gallery seem more real—but they are just as much showing one viewpoint—another kind of persuasive effort that contrasts well with the upper galleries. A guy can’t help but wonder what sorts of images our political candidates can paint when $1 million fundraisers are the standard fare. A lotta loot buys a lotta propaganda.

Go soon—the exhibit closes shop in August.

###

Image credit: Vladimir Petrovich Tomilovski via The Museum of Russian Art

Related: Hard-hitting Russian safety posters that need no translation

I don’t always wear clothing, but when I do…

How a Leaderless Team Ruled Project Runway

OK: bait and switch. I typically wear clothing. And if you know me, I doubt fashion comes to mind. But my costume-designing wife and the fashionistas in our house started watching this show. And I’ve started to like it because it parallels my work of producing copy that must be new and unique while fitting tight space, tone, accuracy and brand requirements.

OK: bait and switch. I typically wear clothing. And if you know me, I doubt fashion comes to mind. But my costume-designing wife and the fashionistas in our house started watching this show. And I’ve started to like it because it parallels my work of producing copy that must be new and unique while fitting tight space, tone, accuracy and brand requirements.

Season 8 episode [whatever] featured a group exercise. This was poignant for me because when I teach professional writing at Northwestern College, I often include a group exercise. The group exercise is universally hated. For all the reasons you might expect: it’s hard to define what the group is doing together. There’s always someone who fits the slacker role. No one wants to take charge and if the work isn’t up to par, it feels like someone else’s fault.

Next time I introduce a group project, I’ll use Project Runway Season 8 Disc 2 [yes. I am a Netflixer] to set up the team task. That episode shows an outstanding example of what can happens when a leaderless team backs away from personal project management and allows each member to find their own way. Some bit of magic happened in the show that allowed each designer to do their own thing while still producing garments that seemed to belong together. It’s as if they were listening to each other at a level beyond the words used. Leaderless teams don’t always work that way. But that it worked that way once gives me hope.

In contrast, the team with the heavy-handed project manager forced every member to work down at a level beneath their abilities. The judges held that team’s feet to the fire with blistering reviews.

I am intrigued by what can happen when creative people work together. Perhaps the best leader helps their team hear and understand each other so each creator’s personal best is produced rather than some spiritless guess about what the bully micro-manager wanted.

###

Image credit: 4CP via thisisnthappiness

Joseph, Seth Godin’s Dip and Knowing When to Quit

Practice Your Craft In the Dip Or On The Rise

It’s funny what ideas collide on any given day. I’ve been re-reading Seth Godin’s The Dip while also re-reading the ancient text Genesis. In Genesis I’m at the point in the story where the Creator needs to clear out his favorite people—the ones He’ll use to help all subsequent generations and peoples—to a foreign land so they’ll survive a famine. The front man is Joseph, sold into economic slavery by his not-so-well-meaning brothers. Joseph winds up as #2 man in Egypt. You know the story. Maybe you are already singing the tune from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

It turns out not just any dream will do, as Mr. Osmond so famously sang, because there were a lot of very big falls and rises in Joseph’s life. And a lot of waiting, which served to focus the dream. Quitting would have been an excellent option for any of the many dips he experienced. Because there were no guarantees the dip would ever end. There were no guarantees he would ever rise out of the slavery/prison. Interestingly, the author of Genesis points out that Joseph continued to work out the processes behind his dream: his gift for organizing people and stuff. His gift of leadership. So that wherever he was, as household slave or in jail, he organized and led using the same skills that would help him manage a nation’s food supply through thick years and thin.

The dream seemed to be about fame at the beginning—that’s what Joseph’s brother’s thought. Maybe Joseph thought that too. But the dream became a byproduct of practicing the gifts given him, even at the lowest points of the dip. To quit would have been to stop practicing the thing he was made for, which would be to give up hope. I think Webber did a good job capturing the optimism that must have been warp and woof of Joseph’s life.

Where does that optimism come from? Maybe from practicing one’s craft when up or when down. Maybe that optimism comes from understanding a much larger plan is in the works and you are in it, whether you on the rise or languishing in the dip.

###

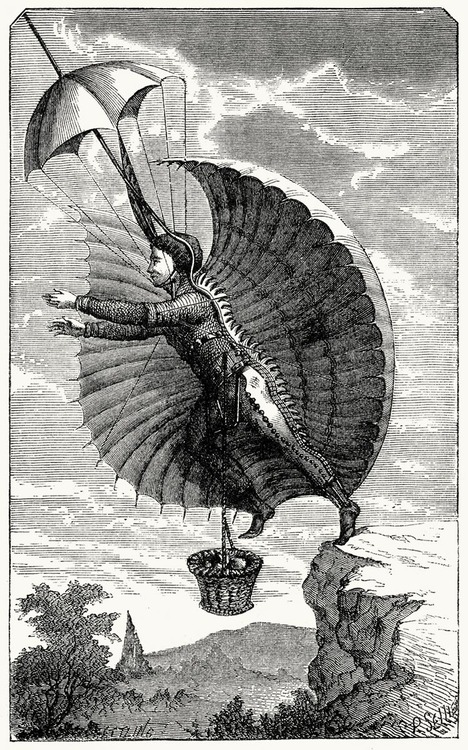

Image credit: Scribner’s Monthly Via OBI Scrapbook Blog

Getting Voice Right

Speaking for Someone Else is Always a Collaboration

Speaking in someone else’s voice is not really possible, though copywriters are often called on to do just this. The process—when done well—is more like hearing the client’s messages and collaborating to expand and deepen those messages. If the goal was just getting the words right and getting the message out clearly, strong editing would suffice. But the strategic copywriter often contributes substantive content. Helping the original ideas along by serving as a conversation partner to the client, to help them process through the message and its ramifications. The resulting content can prove stronger than the original content, though the danger is that it can sound like a committee wrote it. But a strong copywriter owns the process and follows through with a singular voice.

Speaking in someone else’s voice is not really possible, though copywriters are often called on to do just this. The process—when done well—is more like hearing the client’s messages and collaborating to expand and deepen those messages. If the goal was just getting the words right and getting the message out clearly, strong editing would suffice. But the strategic copywriter often contributes substantive content. Helping the original ideas along by serving as a conversation partner to the client, to help them process through the message and its ramifications. The resulting content can prove stronger than the original content, though the danger is that it can sound like a committee wrote it. But a strong copywriter owns the process and follows through with a singular voice.

A singular, compelling voice.

These old Miller High Life commercials help make that point. These were filmed in the 90’s, directed by Errol Morris through Wieden+Kennedy. The retro male voice is just over the edge to make you laugh, but there is a bit of truth in the way the Americana is presented. The voice-over is perfect—and a perfect throw-back to 1950s and 1960s. That’s where Miller wanted the target audience to dwell for 30 seconds—with that slight whiff of what a man once was. Or at least what the Miller/Wieden+Kennedy collaboration thought might produce spending behaviors. And they succeeded: throughout the set there is the slightest hint of something you sorta remember—something your dad’s friends said. Or maybe your grandfather’s friends.

You’ll find a bunch of Errol Morris-directed Miller commercials here, but “Broken Window” (below) does a good job of capturing our grown up fear of the Other.

###

Image Credit: doylepartners.com via 2headedsnake