Archive for the ‘Communication is about relationship’ Category

Am I a constructivist?

Not sure. So I’ll jump.

There’s an old notion—an image, really—of jumping off a high point and building wings as you fall. That’s the image Paul Watzlawick offered as he began his account of constructivism in The Invented Reality (NY: Norton, 1984). Constructivism is a way of thinking about how the world works and how we know anything. Constructivism would say we invent reality as we move forward, as we talk and walk and work. Wikipedia’s entry on constructivism as an educational theory seems like a reasonable synopsis. I definitely cannot buy into the whole thing (few “–ism’s” are entirely believable), but there are pieces of constructivism that ring true:

- My growing theory of a conversation has elements of constructivism: what happens between us as we talk is a new thing constructed on the spot (and, frankly, from past conversations and experiences). Our communication and relationship morph with each engagement.

- Aphorisms and self-fulfilling prophecies do have a certain amount of power in anyone’s life to adjust expectations if not experience—give or take/depends/your mileage may vary.

- In writing, my argument or story unfolds entirely dependent on my word choices. Outcomes change before my eyes as I write, not just in fiction, but also as I sort through a business problem.

One wants to be very careful—of course—about agreeing entirely with any particular -ism. In philosophy and theology, to agree to one thing is to disagree with another, and sometimes unwittingly. All the threads are connected, so when you pull on one, something unravels on the other side of the garment. I can see from just this little glimpse that constructivism might be hostile toward the notion of a central truth in life, which would not fit with my theological commitments. Constructivism also has wise-cracks to make about the determinism/free-will debate raging in my brain. And yet, there is some truth to the constructivist way of seeing life.

What do you think? Are we all making it up as we go?

###

Image credit: Dustin Harbin via 2headedsnake

Let Us Never Speak of This Again: “Obviously”

One Word That Cannot Be Rehabilitated

It’s rarely obvious when someone says “obviously.” It may be obvious to you, stuck away in the cinema of your mind, but it’s probably not obvious to me. I don’t see what you see. I haven’t had your experiences. You have not had mine. All those experiences color the lens of our understanding.

It’s rarely obvious when someone says “obviously.” It may be obvious to you, stuck away in the cinema of your mind, but it’s probably not obvious to me. I don’t see what you see. I haven’t had your experiences. You have not had mine. All those experiences color the lens of our understanding.

“Obviously” is almost always misleading. It nearly always leads to some untruth (just like when your financial planner says “Trust me on this.” That is your cue to run—fast—the other way.)

“Obviously” is condescending. When I say it, I am surprised that you don’t see what is so clear to me. Maybe I think less of you precisely because you don’t see what I see. It’s all so obvious. What do you mean you don’t see it?

If language is about making meaning together and some words can be reshaped to hold the meanings we need to communicate, this isn’t one of them. “Obviously” is a dead-end in a conversation. It seals off further dialogue because of all it assumes about the people present. If I say “obviously” to my conversation partner and she doesn’t get it, I’ve put her in the awkward position of needing to admit she doesn’t see what I see. And that inhibits dialogue. “Obviously” is another power word that hints at more knowledge/style/panache than it delivers.

No one can ban a word. And some words can and should be taken to rehab. But I’ll turn my back on “obviously” and walk away, never finding reason to utter it again.

###

Image credit: Alfred Steiner via 2headedsnake

Take this Word to Rehab: “Out”

A Meditation Beyond Gay

A few days back I posted There’s Something About Out (Out Always Informs In) and noticed a slight uptick in hits. My theory: the uptick had to do with the word “out” in the headline and subhead, a signal word for the LGBT community. Walk with me as I argue the value of “out” is beyond ownership by any particular set of people and is useful for anyone trying to communicate to those outside their immediate peers.

A few days back I posted There’s Something About Out (Out Always Informs In) and noticed a slight uptick in hits. My theory: the uptick had to do with the word “out” in the headline and subhead, a signal word for the LGBT community. Walk with me as I argue the value of “out” is beyond ownership by any particular set of people and is useful for anyone trying to communicate to those outside their immediate peers.

One lesson to be learned these days is the walls that traditionally provided sharp borders for any community are falling quickly. Social media opens a rolling window into nearly any group—if you know the right search keywords. With keyword searches we expose what poets and writers are doing, what glass-blowers and comic-con enthusiasts and copywriters and geocachers are up to. The corollary is that if you are in a tightly-delineated group with high walls, there has never been a better time to begin to explain yourself to those outside, because someone is likely peering in.

Out is more and more important—especially since we battle xenophobia (fear of strangers) on so many different levels: acute and generalized, nationally, locally, in Congress and on the street. Fear of strangers ought to be decreasing given increasing frequency, but it seems the opposite is happening.

In my copywriting practice I often help clients organize their thoughts for those outside the organization. How difficult can that be? Good question. The truth is that we all get caught up using shorthand, insider terms that have less to do with communication and more to do with identifying others who are part of our tribe. Real communication happens when we make our ideas and ourselves accessible to those not from our neighborhood or company or tribe or sect.

The challenge of “out” is communication beyond our self-inscribed language borders. First we need to identify the borders (and possibly our tribe). Then we need to know what’s important and remarkable that someone outside would care about. The challenge of “out” is to step outside our circle with honest, clear language that also happens to make us vulnerable. But those things that are important to us are worth sharing.

Other words in need of rehab: fellowship, strategy, and maybe “lovingkindness.”

###

Image credit: Corrado Zeni via 2headedsnake

Juxtapose: How To Build a Church that Counters Culture

Theological Roots and Practical Hope for Extreme Listening and Honest Talk

Theological Roots and Practical Hope for Extreme Listening and Honest Talk

A couple nights ago Mrs. Kirkistan and I had dinner with old friends we’d not seen in some time. It was refreshing to catch up and there was lots of that free laughter that happens when old jokes and forgotten quirks reappear. At one point someone asked whether we were hopeful about the state of the evangelical church. We each offered an opinion.

Mine: “No.”

It’s actually a qualified “No”: my sense is that the evangelicalism has largely lost its way following industrial-strength, church-growth formulas and it has also sold its soul to political machinery. Following these tangents we’ve lost the essence of what it means to counter culture by speaking the words that stand outside of time.

I’m actually quite hopeful about what God is doing—especially in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area. We’ve seen a number of groups trying very new things while employing deeply-rooted devotion to sacred texts and veering from partisan nonsense. So my sense is that evangelicalism is morphing and, frankly (I hope) growing up.

For a couple years now I’ve been laying down about a thousand words a day toward this book dealing with the theological and philosophical roots of communication. It’s been a one-step-forward-seven-steps-back process. But I’ve just finished Chapter 8 and by the end of July I’ll deliver the manuscript to my editor friend. I’ll likely self-publish it later this year—I’ll probably have to pay people to read it (Know this: I cannot afford more than $5 a reader. So both of you readers give a call when you are ready. I’ll put a fresh Lincoln in the Preface.)

The book offers new ways to think about the ordinary interactions we have every day. It draws on a few philosophically-minded thinkers and reconsiders some old Bible stories to reframe the opportunity of conversation. It also provides a kick in the butt to move out of our familiar four walls to engage deeply with culture—but not from a standpoint of judgment, rather from a deep curiosity and love. I’ll be sharpening the marketing messages over the next few months, but here are the chapter titles so far:

- The Preacher, Farmer and Everybody Else

- Intent Changes How We Act Together

- How to be with the God Intent on Reunion

- Your Church as a Conversation Factory

- Extreme Listening

- A Guide to Honest Talk

- Prayer Informs Listening and Talking

- Go Juxtapose

Let me know if anything of what I’ve said sounds like you might actually be interested in reading. However: I can only afford to buy a limited number of readers.

###

Image credit: Daniele Buetti via 2headedsnake

Untangling Faith and Politics

Kids: Can an Empire Pray?

The generation before me worked hard to tie faith with politics so the two landed together like a dense brick every time one or the other was mentioned. The Moral Majority was a beginning point back in 1979 and all sorts of offshoots and sister organizations continue the cause today. The sad bit, the unanticipated piece, was that the next generation saw faith and right-leaning gibberish as the same thing. Press the vending machine button for one and you always get the other—package deal. So when the next generation rebelled (as each next generation will), they had to toss out everything.

The generation before me worked hard to tie faith with politics so the two landed together like a dense brick every time one or the other was mentioned. The Moral Majority was a beginning point back in 1979 and all sorts of offshoots and sister organizations continue the cause today. The sad bit, the unanticipated piece, was that the next generation saw faith and right-leaning gibberish as the same thing. Press the vending machine button for one and you always get the other—package deal. So when the next generation rebelled (as each next generation will), they had to toss out everything.

But start to untangle the two (faith and politics). As you do, you may remember that Christianity was a counter-culture set of priorities and commitments that offered critiques of whatever society/kingdom/regime it popped up in. And for a long time it was a faith that lived on the periphery, with Jesus as persona non grata. I’m beginning to think Christianity is most effective when living on the periphery and least effective when the state wields it as another tool for empire-building.

Of course, the truth is that faith and politics are intimately tied together. One’s faith absolutely informs one’s stance on any and every issue along with one’s voting record. But the question is what relation faith has to do with empire-building. Is faith a tool for building an empire? My reading of the Bible leaves me with a clear and emphatic: “No.”

I think of this as friends try to find ways to help their kids grow their interior lives and their lives of faith. It’s not an easy task in our culture for a few reasons. One reason is that the very notion of an interior life is drying up for many of us as silence recedes with each Facebook status check-in. But beyond that, asking questions that begin to separate faith from politics may be a way to help your kids find their way through their particular rebellion with faith thriving rather than dying.

###

Image credit: nancyishappy via 2headedsnake

Ben Kyle: Hey—What if We Did a Living Room Tour?

The Dog Days of DIY

There is no one on the other end of this telephone connection who can help set up my new smartphone. With my last several technology purchases I’ve found myself alone in the final fine-tuning that actually makes the device work. Oh—there is certainly tech support. But my questions seem to send the customer representative to their supervisor (>30 minutes on hold) for answers. Not because I’m so smart, only because I am the chief of my cobbled-together IT system and I seem to always demand awkward things of said system. This is my penance for pushing for non-standard capabilities.

There is no one on the other end of this telephone connection who can help set up my new smartphone. With my last several technology purchases I’ve found myself alone in the final fine-tuning that actually makes the device work. Oh—there is certainly tech support. But my questions seem to send the customer representative to their supervisor (>30 minutes on hold) for answers. Not because I’m so smart, only because I am the chief of my cobbled-together IT system and I seem to always demand awkward things of said system. This is my penance for pushing for non-standard capabilities.

But maybe do it yourself is not such a bad set of expectations.

And maybe do it yourself is the future of, well, everything.

A local artist I find myself listening to again and again—Ben Kyle of Romantica—seems to be doing this very thing. He’s taking his music into the homes of friends and strangers. Right into their living rooms. Pot-luck and BYOB. Sign up here and you’ll see Ben singing from the ottoman. Can this be literally true—have I got this right?

If so, I’m watching for other artists to do the same. Why not run a DIY art gallery (oh, wait, that’s been done for years). Why not bribe neighbors with brats and beer to come to my book reading? Why not summon an interpretive dance-off on my front lawn?

As a nation we’ve always been enamored by fame. Anyone’s definition of “making it” inevitably carries some component of fame. You’re a success when everyone knows your name. If everyone knows your name you are a success. How else to account for the seeming success of the Kardashians who are famous for being famous?

But this DIY future doesn’t look like mass audiences following influential taste-makers. At least not at first. Ben Kyle is on to something that real influencers have known for years, that building an audience is a person-by-person activity. This is the word-of-mouth model: generally slow but immensely effective.

And maybe anything worth doing is worth doing one-on-one, despite what our national psyche longs for. I’m with Mother Teresa on this one:

Do not wait for leaders; do it alone, person to person.

###

Image credit: Francesco Romoli via 2headedsnake

There’s Something About Out

Out Always Informs In

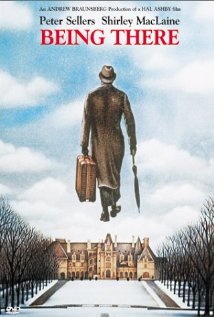

Chance tended the garden of a wealthy old man in Washington D.C. and had done so all his life. When his wealthy employer died, Chance was turned out into the [mean] streets. All Chance knew was the calm of the mansion and all he knew about the world outside was what he saw on TV. And so began Being There, one of the last films made with Peter Sellers way back in 1979. You might call Being There a dark comedy and it was certainly not for every audience.

Chance tended the garden of a wealthy old man in Washington D.C. and had done so all his life. When his wealthy employer died, Chance was turned out into the [mean] streets. All Chance knew was the calm of the mansion and all he knew about the world outside was what he saw on TV. And so began Being There, one of the last films made with Peter Sellers way back in 1979. You might call Being There a dark comedy and it was certainly not for every audience.

The scene playing in my mind today is Chance stepping away from the calm of the mansion and out into the urban chaos, complete with garbage everywhere, burning cars and a host of other stereotypes. The movie is all about how he is received by those he encountered.

In a sense Chance came alive as he left the stately known environment. This fits with what I’m coming to understand about taking what I know out to others who don’t know it. Whether it is what I know about medical devices or carbon fiber or my theological and faith commitments or what I know about bicycle routes in Minneapolis/St. Paul. Whatever I know, whatever is familiar to me changes in perspective the moment I try to explain it to someone else. Maybe I succeed in convincing my biking friend to take the river route I like. Maybe I fail to get my reading friend to take interest in the book I liked. Maybe I’m helping my client explain a unique heart monitoring system to an audience of physicians. Whatever it is—and in every case—how I explain myself to those outside changes the way I look at the priority. I immediately learn something new as I try to explain. And the organization changes as the communication happens: as we form words together to explain out product to an outsider, we on the inside understand something different as well.

And it’s not just what I know, it’s what is important to me. And maybe this is the heart of the learning: can this thing be important for someone else? And if so why or why not? And all this communication changes us.

My only point is that we need to actively take our priorities and knowledge with us out into the relationships we feed throughout every day. That’s how we grow.

###

Why I Like the Dumb Sketch Approach to Life

The Lure of Rough Drafts, Quick Observations and Badly Drawn Lines

I made this dumb sketch when visiting our son working in Madison, Wisconsin. Madison holds lots of memories for Mrs. Kirkistan and I: we went to school and met at the UW, we met amazing people who remain friends today decades later and made big directional choices. It was a place for fiddling with and setting trajectory—it still is that today.

Like most summer weekends there was a concert on the Memorial Union Terrace. This jazz festival (see dumb sketch) was running all weekend. These days it seems all of Madison turns out at the Terrace.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

One of the functions I relish as a copywriter is this responsibility to provide a rough draft. The rough draft is this work of writing out the position or power of my client’s product or service so others can respond. Or sometimes I’m summarizing and sharpening the science behind a product so we can see more clearly why it is important. Rough drafts are both right and wrong at the same time. The power of the rough draft is to set a thought out in the open where others can reach and tag it. After all, you can’t change something that doesn’t exist. The point is collaboration: how is this right? What do we know that can make this more right?

Saying aloud what we know and what we believe is the verbal equivalent of a rough draft. And saying aloud what we know is more than helpful. It is part of the human condition and not to be missed. Our conversations reveal who we are and what we know even as they and invite participation. Getting it wrong sometimes is part of the deal.

That seems like a good approach to life.

###

Image credit: Kirkistan

The Infallibility Problem

Sacred texts don’t change so it must be our reading

When I was a kid we made fun of Roman Catholicism because they had a guy in a robe and funny hat who told everyone else what was right and wrong for all time. But what was right and wrong for all time seemed to change depending on the robed/hatted officeholder. This was hilarious to us: how could what was right become wrong and vice versa? If things were really true they would not change. Ha ha—gullible people. My people took marching orders straight from the Bible and that didn’t change.

Years later I realized nearly every one of us erects our own pope: someone who interpreted the sacred texts for us and whom we believed without question. Whomever stood behind the pulpit was a potential pope. For some it was Billy Graham or John Piper. Others looked to Carl Sagan. For a while Richard Dawkins seemed to be pope for hard-line atheists, but a new batch of atheists are sounding sympathetic to what can be learned from conversation with the faithful.

Years later I realized nearly every one of us erects our own pope: someone who interpreted the sacred texts for us and whom we believed without question. Whomever stood behind the pulpit was a potential pope. For some it was Billy Graham or John Piper. Others looked to Carl Sagan. For a while Richard Dawkins seemed to be pope for hard-line atheists, but a new batch of atheists are sounding sympathetic to what can be learned from conversation with the faithful.

Mind you, I’m not arguing there is no truth. I believe in truth and I believe it can be known by regular people. And I’m arguing for sacred texts (not against): I scour the Bible, want to hear from it and I try hard not to believe everything I think. Only because we humans have this odd predilection to read whatever we want into a text. Any text. Especially a text composed hundreds of years ago in very different cultures by wildly different authors. But what pulls me back to the Bible is the sense of hearing what God might be saying to us today, across generations and cultures and centuries. And the stories about Jesus the Christ pull me back big time—has there ever been anyone like him?

That’s why I don’t believe any one guy or gal owns it. Just like I don’t believe any single reading is the perfect reading. We’re all flawed and we all have only imperfect understanding of the truth. But when we combine our understandings of the truth, that’s when stuff starts to happen. My point is that none of us has a handle on the complete truth—and we desperately need to hear from each other.

I was reminded of this as Alan Chambers, president of Exodus International announced last week the closing of the ministry that aimed to help gay folks become straight folks. His announcement included something of an apology for the people that had been hurt through the years, including the notion that the ministry had been responsible for “years of undue suffering.” How Chambers said it was pretty interesting, at least as reported by David Crary for the Associated Press (and appearing in the StarTribune):

“I hold to a biblical view that the original intent for sexuality was designed for heterosexual marriage,” he said. “Yet I realize there are a lot of people who fall outside of that, gay and straight … It’s time to find out how we can pursue the common good.”

Two things I like about this story:

- I like hearing people of faith apologize for inflicting suffering. Mr. Chambers’ apology strikes me as bold. People will take that apology as real or lacking or simply more PR (letters to the Strib include all of the above and Salon finds the apology lacking), but it is a statement out there in the open that would most certainly produce a substantial loss of funding, were the organization to continue. I like the apology also because I’ve wondered what suffering I’ve inflicted on others because of my faith. Apologizing seems like a good communication strategy for repentant bullies like me.

- I like hearing Mr. Chambers hold to his understanding of the sacred texts. There is no getting around the fact that the texts do not point to the broad acceptance our culture seeks. And for those of us who hold those texts in high regard as words from God, our deep listening must include lots of wrestling: were they just unenlightened back then or are there theological truths we must still unearth and process together in conversation? And what do those truths look like, given the great varieties of people on the planet?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston