Archive for the ‘Teaching writing’ Category

Get a Job. Or Don’t.

Rethinking My Standard Line on Employment

What to say to folks starting in this job market?

I’m gearing up to teach a couple professional writing classes at the University of Northwestern—St. Paul. I’ll be updating my syllabi, looking at a new text or two. I’ve got some new ideas about how the courses should unfold and about how I can get more discussion and less of that nasty blathery/lecture stuff from me. I’ll be thinking about writing projects that move closer to what copywriters and content strategists do day in and day out.

One thing I’m also doing is reconsidering the standard advice for people on the cusp of a working life. I usually tell the brightest students—the ones who want to write for a living and show every indication of being capable of carrying that out—to start with a company. Starting with a company helps pay down debt, provides health insurance (often) and best of all, you learn the ropes and cycles of the business and industry. I’ve often thought of those first jobs out of college as a sort of finishing school or mini-graduate school where you get paid to learn the details of an industry (or industries). Those first jobs can set a course the later jobs. And those first friendships bloom in all sorts of unlikely ways as peers also make their way through work and life. You connect and reconnect for years and years.

But I’m no longer so certain of that advice. While it’s true that companies and agencies and marketing firms provide terrific entry ramps to the work world, they also open the door to some work habits that are not so great. Every business has its own culture, of course. Sometimes that culture looks like back-biting and demeaning and discouraging. Sometimes the work culture can be optimistic and recognize accomplishment and encouraging and fun. Mostly it’s a mix of both.

But one thing I don’t want these bright students to learn at some corporate finishing school is the habit of just doing their job. By that I mean the habit of waiting for someone to tell them what to do. Every year I watch talented friends get laid off from high-powered jobs in stable industries where they worked hard at exactly what they were asked to do. And most everyone at some point says something like:

Wait—I should have been thinking all along about what I want to do. [or]

How can I be more entrepreneurial with my skill set? [or]

What exactly is my vision for my work life?

Some of these bright writing students are meant to be entrepreneurial from the very beginning. Though a rocky and difficult path in getting established with clients and earning consistently, it may be a more stable way to live down the road. Maybe “stable” is not quite the right word for the entrepreneurial bent—“sustainable” might be more appropriate. The quintessential habit to learn is to depend on yourself (while also asking God for help, you understand) rather than waiting for someone to come tell you what to do.

I’m eager for these bright, accomplished people to think beyond the narrow vision of just getting a job. The vision they develop will power all sorts of industries over time.

###

Image credit: arcaneimages, via rrrick/2headedsnake

Tell Me What You Know. Wait: Mime It Instead.

Nancy Dixon & Is there a best way to transfer knowledge?

Lecture is not effective.

As one who has lectured and been lectured unto, I’ll insist that listening is hard work when seated before a droning human. Sermons are the same species. Occasionally sermons are more spirited than lectures but both have roughly the same effect. Maybe there is a continuum for lecturing: previous generations felt ripped-off if the person in front did not speak at length and without interruption. For the generations I teach, 15 minutes is the absolute maximum before reengaging with questions or activities or just standing and moving chairs around the room.

Working alongside someone is amazingly effective at transferring knowledge. To have a common task with a colleague or mentor bypasses much of the resistance and passivity that comes with the classroom “listen-to-me-I’m-the-expert” experience. The focus is on the doing and learning takes care of itself.

Nancy Dixon in her Common Knowledge: How Companies Thrive by Sharing What They Know (Harvard Business School Press, 2000), breaks the transfer of knowledge into manageable buckets as she shows how organizations do the work of helping teams and individuals learn. She starts by making a distinction between tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge: tacit knowledge is what we just sort of know. It’s the multiple bits of knowledge that would be difficult/impossible to write down. Explicit knowledge is written: it’s explicit in the sense that someone could pick it up, read it and know. Dixon cites five ways teams have successfully transferred what they know:

- Serial Transfer: team does a task and then does the same task again in a different location/venue. The team collects and discusses what they learned between, so each time they do the task a bit more efficiently.

- Near Transfer: Transferring knowledge from a source team to a receiving team doing a similar (routine) task.

- Far Transfer: Transferring tacit knowledge from a source team to a receiving team doing a non-routine task.

- Strategic Transfer: Knowledge transferred impacts an entire organization rather than just a team. Maybe that knowledge comes from the entire organization.

- Expert Transfer: Team facing problem beyond scope of its knowledge reaches out to an expert or expert team.

I like how Dixon positions the expert as a sort of higher-order transfer: where the audience is engaged and invested and eager for the solution. I also like Dixon’s discussion of knowledge as both dynamic (knowledge is less of a warehouse and more of a river) and also becoming more of a group phenomenon.

I like how Dixon positions the expert as a sort of higher-order transfer: where the audience is engaged and invested and eager for the solution. I also like Dixon’s discussion of knowledge as both dynamic (knowledge is less of a warehouse and more of a river) and also becoming more of a group phenomenon.

Working alongside learners and experts is a great benefit of day-to-day work, though we don’t always appreciate it.

###

Image credit: exploitastic via 2headedsnake

What Business Can Learn From Church #1: Relational Trumps Transactional

Identify and Hear Gifted Voices

Seth McCoy runs a coffee shop in the Hamline Midway neighborhood of St. Paul. Groundswell makes an irresistible Chai Cinnamon Roll—especially warm.

Especially first thing in the morning.

Seth McCoy also pastors a church blocks away. A new sort of church that takes seriously the notion that people benefit more from dialogue than monologue.

Church and coffee shop each vigorously pursue their mandates: Groundswell makes tasty foods and strong coffee in a high-ceilinged, inviting neighborhood space. Third Way Church takes seriously the notion that community is much more than one guy sermonizing for an hour—you are likely to hear many voices if you show up at a gathering. Groundswell and Third Way Church inhabit the same neighborhood. This community connection also begins to bridge traditional divides, like the sacred/secular myth.

Talk with Seth the business owner and he may tell you how the leadership team works at Third Way Church: discussions can get “heated,” which is to say, leaders are passionate and vocal. One gets the sense they don’t hold back. On the church leadership team they’ve identified different giftedness or abilities in each of the leaders and they try to honor that particular voice. Often leadership voices in a church can follow some of the traditional patterns of prophet/apostle/evangelist/shepherd. Team members speak consistently from their expertise—which is also their natural bent—and they speak with authority.

Our businesses are typically more transactional affairs. Employees are hired with a set of expectations (whether narrow or wide) and expected to go about their business. Our best work situations are those that move beyond merely transactional and begin to see the various bits of giftedness each employee brings—and then honors that voice. Most of us who have worked in organizations and companies where we remained unheard—and those work situations number among our least favorite. And those best work situations were where we were identified as the person in the know on some particular aspect of the shared vision.

Our businesses are typically more transactional affairs. Employees are hired with a set of expectations (whether narrow or wide) and expected to go about their business. Our best work situations are those that move beyond merely transactional and begin to see the various bits of giftedness each employee brings—and then honors that voice. Most of us who have worked in organizations and companies where we remained unheard—and those work situations number among our least favorite. And those best work situations were where we were identified as the person in the know on some particular aspect of the shared vision.

Business can learn from church by recognizing the gifts, abilities and particular bent of employees and hearing the authority that employee speaks from. No matter what position the employee has, there is some authority/expertise/giftedness they bring.

We owe it to each other to move beyond transactional to relational.

###

What Pulls You In Again and Again?

A Photo. A Paragraph. A Word That Helps You Understand.

I’ve stumbled at least twice over this useful blurb about writing. I’m not the only one to find and re-find it: a number of Twitterers keep tweeting this particular blog post. It’s from the Australian writer Charlotte Wood who wrote a guest blog back in 2011 for an Australian philosopher I enjoy: Damon Young (‘The Write Tools’ #32 – Charlotte Wood). Ms. Wood wrote about her process for producing novels and how at a certain point in the process she starts to take photos as a way of capturing detail. The entire post is worth your time, but I keep rereading this paragraph:

I’ve stumbled at least twice over this useful blurb about writing. I’m not the only one to find and re-find it: a number of Twitterers keep tweeting this particular blog post. It’s from the Australian writer Charlotte Wood who wrote a guest blog back in 2011 for an Australian philosopher I enjoy: Damon Young (‘The Write Tools’ #32 – Charlotte Wood). Ms. Wood wrote about her process for producing novels and how at a certain point in the process she starts to take photos as a way of capturing detail. The entire post is worth your time, but I keep rereading this paragraph:

Iris Murdoch said that paying attention is in itself a moral act. I think this is true – it is hard to dismiss someone if you listen very carefully and watch them, and enter into what they truly believe. I think this is what my photographs and notebooks are telling me: remember not to skate over the surface of an imagined thing or person or act, but really sit, and go quiet, and listen. Pay attention to everything there in the frame, and then also perhaps wonder about what is not there, and why. I think a commitment to paying attention is perhaps as good a way as any to try to understand the world. And trying to understand the world is why I read, and why I write.

Ms. Wood’s attention to detail is a source of inspiration to me. And I like how reading, writing and observing are all helping serve her goal of understanding.

###

Image credit: Kateoplis via 2headedsnake

Table 7: The typist’s quiet laugh is every writer’s dream

Four minute film from Marko Slavnic

###

Why I Want To Do What Others Don’t (Shop Talk #6)

Guest Post from Kayla Schwartz

[A few of us have been discussing what fulfillment looks like for a professional writer. The entire discussion was in a response to a question from Kayla Schwartz, a professional writing student at Northwestern College. Check out these six essays filed under Shop Talk: The Collision of Craft, Faith and Service for more on that. Kayla’s back with this guest post that contains a few of her thoughts and conclusions.]

“Technical writing? That’s so…interesting.”

This is the response I usually get when I tell people what I’m studying. As a professional writing major, I’ve done journalism and PR writing, but I’ve been most drawn to technical writing.

Why? I had not given it much thought. Most people think of technical writing as boring or tedious. So why pursue it? What really drives technical writers?

As I’ve thought about these questions and talked to technical and other professional writers who’ve been at it much longer than I, I’ve gleaned a few potential answers.

- It’s useful. Some people find a lot of satisfaction in their ability to help others understand things. They feel they are making a difference.

- It’s necessary. Technical manuals may not always be read by customers, but they are a necessary step in the process of distributing the product. There is satisfaction in contributing to a company’s success.

- It’s interesting. For people who are naturally curious, technical writing offers an ideal situation: learn about new ideas and products, and get paid for writing about them.

- It’s lucrative. Yes, some people are just looking for something that pays the bills.

All of these are valid reasons to do technical writing. However, none of them really expresses my motivation (although the last one is starting to look pretty good when I think about my student loans).

I’m pursuing technical writing because I genuinely enjoy it. I like creating an organized, easy-to-follow document. I like figuring out how to use words effectively and concisely. I’m a bit of a perfectionist and don’t mind spending time on “minor” details. I suppose I enjoy learning about new things or knowing that I’m helping others, but ultimately, it’s a way to do what I love.

Maybe this makes me the exception among technical writers, but I hope not. Technical writing isn’t for everyone, but for those of us who enjoy it, it can be just as satisfying as any other career.

###

Image credit: George Brettingham Sowerby via OBI Scrapbook Blog

Why Teach?

Teaching is an epistemological playground

Yesterday I posted under the title “The unbearable sadness of adjunct.” I hope you read on to see it was a larger discussion about the price anyone pays to live a thoughtful life. I tried to show the realities of teaching as an adjunct (often agreeing with Burnt-Out Adjunct), especially noting the counterintuitive reality that some advanced degrees still offer jobs that force you to choose between buying groceries or paying the mortgage.

Yesterday I posted under the title “The unbearable sadness of adjunct.” I hope you read on to see it was a larger discussion about the price anyone pays to live a thoughtful life. I tried to show the realities of teaching as an adjunct (often agreeing with Burnt-Out Adjunct), especially noting the counterintuitive reality that some advanced degrees still offer jobs that force you to choose between buying groceries or paying the mortgage.

But there are also good reasons to teach. If you can afford it (counting the work you do to earn a living and/or opportunity costs of time spent on teaching), it is work that is full of meaning. Here are a few reasons I continue to seek opportunities to teach as an adjunct:

- There is a thrilling something about developing a coherent idea and presenting it to a class of students. Even more thrilling, when you see that they see the utility of the idea.

- Class times often become incredible conversations. Not always, but often poignant things get said that help move my thinking (and humanity) to a new level

- To teach is to learn. And learning is great fun. There’s nothing like trying to explain something to someone else to show how little you really know. As I explain, synapses fire and brand new stuff happens in my brainpan. Teaching is a kind of epistemological playground.

- Students are amazing. At the college I teach, I remain deeply impressed by the devotion and care and passion many (not all) bring to the work. I often encounter excellent writers and I want more than anything to help those people move forward.

- Faith and work belong together. Every year I teach I see this more clearly and I labor over (and yes, I pray about) how to explain the connection. My own work as a copywriter highlights and dovetails into this connection. I am very pleased to bring with me ancient texts that explicate the meaning of work and life.

Naturally, there is more to say about this. What would you add?

###

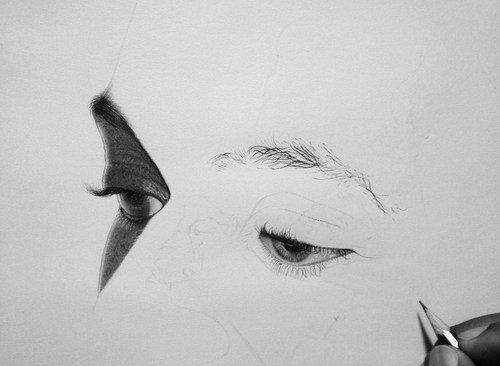

Image credit: Kelvin Okafor via 2headedsnake

The Unbearable Sadness of Adjunct

The Price of the Life of the Mind

I’m having a lively conversation with PissPoorProf about the value of a Liberal Arts degree. He maintains that liberal arts should be corollary studies in college while I think they should be central. Others are chiming in. It’s a discussion I welcome because the topic goes well beyond the choice of undergrad studies. As Burnt-Out Adjunct so ably points out (in his many posts) the life of the mind does not come with an income. In fact, it requires an income to satisfy those lower elements in Maslow’s hierarchy, just to get to the point where one can, well, buy time to think/read/write/converse.

I’m having a lively conversation with PissPoorProf about the value of a Liberal Arts degree. He maintains that liberal arts should be corollary studies in college while I think they should be central. Others are chiming in. It’s a discussion I welcome because the topic goes well beyond the choice of undergrad studies. As Burnt-Out Adjunct so ably points out (in his many posts) the life of the mind does not come with an income. In fact, it requires an income to satisfy those lower elements in Maslow’s hierarchy, just to get to the point where one can, well, buy time to think/read/write/converse.

Agreed.

Also agreed: the treadmill that is adjunct work, with day and night responsibilities (Honest: preparing lecture/discussions, delivering those educational events, responding to questions and grading take way more time than I would have ever believed when I was a cubicle dweller with a steady paycheck) is relentless and seemingly possible only when you have another income. So when PissPoorProf describes adjunct teaching as “about as soul-sucking as a wage-slave job can get,” I tend to agree.

And yet, we agree that the life of the mind—whether taught or caught or pursued or scrimped and saved for—is a thing of value. Maybe part of our equipping for undergrads, as well as for those later in life who want to think, is to help each other understand we need to pay your own way to join the larger conversation.

There is so much more to say about this.

###

Image credit: BORONDO by Arte urbano Madrid via 2headedsnake

How did you become a philosopher?

Claude Lefort on Meeting Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The questions with which Merleau-Ponty was dealing made me feel that they had existed within me before I discovered them. And he himself had a strange way of questioning: he seemed to make up his thoughts as he spoke, rather than merely acquainting us with what he already knew. It was an unusual and disturbing spectacle.

— From “How did you become a philosopher?” by Claude Lefort, translated by Lorna Scott Fox in Philosophy in France Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983) 98

###

Image credit: Jonathan Zawanda via 2headedsnake