Archive for the ‘What is work?’ Category

Lou Gelfand: No More Complaints

How do you love an impossible task?

In darker moments I wonder what good lies in all the words produced, day after day—especially my own words. But if words serve only to remind or tell again the story of a bright spot someone saw, then maybe that is enough. Because bright spots shine a bit of hope.

Lou Gelfand was a bright spot for me.

I am a casual newspaper reader. I read the StarTribune and various news sources on-line. But the StarTribune has been my go-to, privileged (and sometimes angering) source for many years. Lou Gelfand was the long-suffering ombudsman/readers’ representative. For nearly 23 years he listened to complaints and reader’s rants and charges of bias (a countless number, surely). And then he calmly worked it out with words on paper.

Mr. Gelfand’s “If You Ran the Newspaper” columns were a must-read for me because he seemed fearless in taking colleagues and readers and the process itself to task. He aimed for resolution and made everyone mad as he did it. But there was something satisfying in his assessments. His words produced a sort of end-game where conflict and anger were addressed, if not always resolved.

Here’s Mike Meyers, former Strib reporter and friend of Gelfand, on the mood created by Mr. Gelfand’s assessments:

“He was a guy who often ate alone in the cafeteria because reporters were so damned thin-skinned,” Meyers said.

Mr. Gelfand was a kind of pivot point between audience and the communication machinery that was the daily newspaper. It was a no-win position from the beginning—an impossible assignment—which Mr. Gelfand moved forward with aplomb, sympathy and spirit.

His son called him “relentlessly fair” and Gelfand surveyed his own columns and found he split about evenly between backing the paper and the complaining readers.

Read Mr. Gelfand’s obituary here.

###

Image Credit: via Frank T Zumbachs Mysterious World

Wendell Berry Wrote Death Right

The Memory of Old Jack: Is it passion or habit that overtakes us at the end?

Now he feels ahead of him a quietness that he hastens toward. It seems to him that if he does not hasten, his weight will bear him down before he gets there. He reaches the door of his room and opens it….

He goes slowly across the room to his chair, an old high-backed wooden rocker that sits squarely facing the window. This is his outpost, his lookout. Here he has sat in the dark of the early mornings, waiting for light, and again in the long evenings of midsummer, waiting for darkness. He backs up to the chair, leans, takes hold of the arms, and lets himself slowly down onto the seat. “Ah!” He leans back, letting his shoulders and then his head come to rest.

For some time he sits there, getting his breath, grateful to be still after his effort. And then he rises up in his mind as he was when he was strong. He is walking down from the top of his ridge toward a gate in the rock fence. It is the twilight of a day in the height of summer. The day has been hot and long and hard, and he is tired; his shirt and the band of his hat are still wet with sweat….

He does not know why he is there, or where he is going, but he does not question; it is right. Under the slowly darkening sky the countryside has begun to expand into that sense of surrounding distance that it has only at night….

Slowly the glow fades from the valley, the sky darkens, the stars appear, and at last the world is so dark that he can no longer see his legs stretched out in front of him on the ground or his hands lying in his lap; he has come to be vision alone, and the sky over him is filled and glittering with stars. Now he is aware of his fields, the richness of growth in them, their careful patterns and boundaries. In the dark they drowse around him, intimate and expectant.

And now, even among them, he feels his mind coming to rest. A cool breath of air drifts down up on him out of the woods, and he hears a stirring of leaves. He no longer sees the stars. His fields drowse and stir like sleepers, borne toward morning.

Now they break free of his demanding and his praise. He feels them loosen from him and go on.

(Wendell Berry, The Memory of Old Jack, excerpted from Chapter 9)

This is the only way Jack’s story could end. Though, of course, this is not where Jack’s story ends. Pick any story by Wendell Berry and you’ll find the dead very much alive in the memory of the living—just like in real life.

The Memory of Old Jack is another immersive reading experience from Wendell Berry. I’ve never been to Port William (no one has, as far as I understand fiction), but I feel like I grew up not far from there. Mr. Berry presents a way of life that lies just on memory’s periphery for many of us—toward the far end of what we once knew. For others, there will be no memory of such a way of life. It will seem like pure fiction.

One wonders whether memory does not come flooding back in just this way, more real than our many screens today, until in the end it simply overtakes us. I think something like that was behind Dallas Willard’s comment on death.

I hope someone told him.

###

Image credit: Mark Peter Drolet

Get a Job. Or Don’t.

Rethinking My Standard Line on Employment

What to say to folks starting in this job market?

I’m gearing up to teach a couple professional writing classes at the University of Northwestern—St. Paul. I’ll be updating my syllabi, looking at a new text or two. I’ve got some new ideas about how the courses should unfold and about how I can get more discussion and less of that nasty blathery/lecture stuff from me. I’ll be thinking about writing projects that move closer to what copywriters and content strategists do day in and day out.

One thing I’m also doing is reconsidering the standard advice for people on the cusp of a working life. I usually tell the brightest students—the ones who want to write for a living and show every indication of being capable of carrying that out—to start with a company. Starting with a company helps pay down debt, provides health insurance (often) and best of all, you learn the ropes and cycles of the business and industry. I’ve often thought of those first jobs out of college as a sort of finishing school or mini-graduate school where you get paid to learn the details of an industry (or industries). Those first jobs can set a course the later jobs. And those first friendships bloom in all sorts of unlikely ways as peers also make their way through work and life. You connect and reconnect for years and years.

But I’m no longer so certain of that advice. While it’s true that companies and agencies and marketing firms provide terrific entry ramps to the work world, they also open the door to some work habits that are not so great. Every business has its own culture, of course. Sometimes that culture looks like back-biting and demeaning and discouraging. Sometimes the work culture can be optimistic and recognize accomplishment and encouraging and fun. Mostly it’s a mix of both.

But one thing I don’t want these bright students to learn at some corporate finishing school is the habit of just doing their job. By that I mean the habit of waiting for someone to tell them what to do. Every year I watch talented friends get laid off from high-powered jobs in stable industries where they worked hard at exactly what they were asked to do. And most everyone at some point says something like:

Wait—I should have been thinking all along about what I want to do. [or]

How can I be more entrepreneurial with my skill set? [or]

What exactly is my vision for my work life?

Some of these bright writing students are meant to be entrepreneurial from the very beginning. Though a rocky and difficult path in getting established with clients and earning consistently, it may be a more stable way to live down the road. Maybe “stable” is not quite the right word for the entrepreneurial bent—“sustainable” might be more appropriate. The quintessential habit to learn is to depend on yourself (while also asking God for help, you understand) rather than waiting for someone to come tell you what to do.

I’m eager for these bright, accomplished people to think beyond the narrow vision of just getting a job. The vision they develop will power all sorts of industries over time.

###

Image credit: arcaneimages, via rrrick/2headedsnake

Why We Need a Science of Collaboration

Whatcha talkin bout Willis?

When I assign a report that must be completed as a team, my college writing classes get very still. When I explain the assignment will be graded as a team, I hear barely audible groans and see ever-so-slight grimaces. (These are polite writing students, after all.)

It is much simpler to be an individual contributor than a collaborator. The fun of writing is in the discoveries you make as you write. Collaboration seems to negate all that.

So many unknowns in collaboration: will my team care the way I care? How will we divide the work? What if that slacker is on my team? Who will lead this group?

(“Please let it not be me.”)

(“Please, not me.”)

(“Please.”)

And yet working together—collaborating—is one of the essential skills our business communities (and academic communities and faith communities) desperately need. This story from the Association of Clinical Research Professionals (via the ACRP Wire) highlights just how big the stakes might be for future collaborations:

An essential new way to move discoveries forward has emerged in the form of multistakeholder collaborations involving three or more different types of organizations, such as drug companies, government regulators, and patient groups, write Magdalini Papadaki, a research associate, and Gigi Hirsch, a physician-entrepreneur and executive director of the MIT Center for Biomedical Innovation.

The authors are calling for a new “science of collaboration” to learn what works and doesn’t work; to improve how leaders can design, manage, and evaluate collaborations; and to help educate and train future leaders with the necessary organizational and managerial skills.

Part of the problem is that we think collaboration will just happen on its own.

It doesn’t. Someone needs to organize the task. That organization can look like top-down authoritarian leadership or it can look like colleague-helping-colleague asides. Both approaches have their place, as well as the infinite variety of other ways to help a team move forward. People who study and practice these things are my heroes.

I can’t help but agree with Papadaki and Hirsch in calling for a new science of collaboration.

And for those of the writing persuasion, I plead for patience with group work.

Because sometimes the lightning bolt of writing also strikes in a conversation.

###

Image via Ads of the World

College Majors to Avoid + Rebuttal

And back to the work itself

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Yesterday I found myself in disagreement with the Burnt-Out Adjunct (whose too-infrequent posts I eagerly await and enjoy) who wrote that liberal arts studies should be more corollary than central to a college degree. Pisspoorprof was reflecting on another of these “ten worst” articles that pop up from time to time. This time it was Yahoo! Education touting the Four Foolish Majors to Avoid if you are trying to reboot your career.

Liberal arts degrees were the #1 opportunity killer with philosophy a close #2 opportunity killer. By the way, I cannot help but note that the entire article is an advertisement for the continuing services of Yahoo! Education.

As a holder of an undergrad degree in philosophy I both agree and disagree.

- Yes: no one hires a college grad to resolve deep-seated teleology questions (one does that on one’s own time). But to his credit, the VP at Honeywell who gave the OK to hire me (lo these many years ago) did question my stance on freedom vs. determinism.

- No: How about granting a bit of perspective? We need people who can think outside the present job parameters. And we desperately need people to challenge those parameters. Educating people to acquiesce by default is not what we need (though it is a short-term path to cash). Liberal Arts (and especially philosophy, let me say) can help this happen. Yes that sounds like the standard line from any college admissions staff says. Yes it is what professors say as they pass each other in the hallowed halls. No you don’t need a college degree to challenge the system, make a million bucks, make a difference or be homeless.

But studying things that don’t make money has a way of making us more conscious of all that is going on around us. Will it eventually make money? Maybe. Maybe not. But we need people with larger vision who can paint or write or photograph or build a different way of looking at things—however that happens.

What do you think?

###

Image credit: Studio Lindfors via 2headedsnake

Chris Guillebeau & World Domination

The Art of Non-Conformity

I’m halfway through Chris Guillebeau’s “The Art of Non-Conformity” and enjoying it greatly. It’s a very easy read. Even so, Mr. Guillebeau manages to challenge all sorts of commonly accepted ways we wander through life, from corporate culture to the rhetorical jujutsu of the bosses and authorities in our lives to how we decide what is most important. In every case, he invites me to ask my own questions rather than blindly accept whatever is laid before me. But it doesn’t read like a philosophical tract or evangelist’s preachment—it is simply stories from the lives of different non-conformists, which he then applies to the mundane stuff of ordinary, daily life. To surprising ends.

Mr. Guillebeau’s honesty pulls you in and keeps you hooked. He shows successes and failure, which makes the entire project feel more doable.

His book (and blog) place travel high in his own list of life’s important stuff and you cannot help but get the bug yourself. But I also like his ongoing conversation about what success looks like. Maybe success looks like a Porsche. Or maybe it looks like a month in Kuala Lumpur. Or maybe it looks like time to write every day. Or maybe it looks like helping orphans in Africa. Or like time to care for aging parents. But it whatever success looks like, Mr. Guillebeau is certain it is your decision—not anyone else’s.

Which brings me to one his central pivots: the notion of world domination. It’s really a sly way of rejecting the values we receive by osmosis and asking what it is we are really trying to accomplish in life. You dominate the world when you replace and live by your own definitions rather than hefting someone else’s.

Give it a read.

###

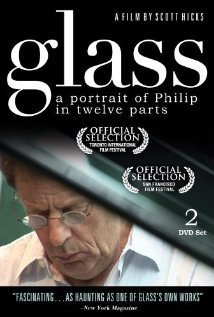

When I get discouraged about writing, I think on Philip Glass

Just Thick-headed Enough

Philip Glass is known for repetitive structures in his music, among other things. Mr. Glass is famous (ish) today and you hear his music most commonly on film soundtracks. But not everyone likes those minimalist, repetitive structures (some members of the politburo of Kirkistan will sit for only limited doses of Mr. Glass’ music).

The 2008 documentary about Philip Glass contained quite a few unguarded responses to his music. Watch the film for the exact quotes, but the general sense people communicated to Mr. Glass as he developed his unique style was something on the order of “Please go away” or “Please stop playing that” or “I think we’ve heard enough of that. Can you do something different?”

In a 2009 Esquire interview, Mr. Glass, said this about his resolve:

When I struck out in my own music language, I took a step out of the world of serious music, according to most of my teachers. But I didn’t care. I could row the boat by myself, you know? I didn’t need to be on the big liner with everybody else.

I often think of Philip Glass when I get discouraged about writing.

Writing is difficult, so says anyone who writes. Just like with anything worth doing, there are all sorts of missteps and problems and wrong directions and mistakes involved with getting a thought on paper. And then there is the problem with the audience. I might call it the Glass Problem: prolific production of something no one wants.

But one continues forward. Despite responses. One must be just thick-headed enough to continue sorting out what it is one is trying to say. That’s what I understand when I think on Philip Glass: an infusion of courage to move forward despite all outward evidences that I really should stop.

###

Image credit: IMDB

Why I Want To Do What Others Don’t (Shop Talk #6)

Guest Post from Kayla Schwartz

[A few of us have been discussing what fulfillment looks like for a professional writer. The entire discussion was in a response to a question from Kayla Schwartz, a professional writing student at Northwestern College. Check out these six essays filed under Shop Talk: The Collision of Craft, Faith and Service for more on that. Kayla’s back with this guest post that contains a few of her thoughts and conclusions.]

“Technical writing? That’s so…interesting.”

This is the response I usually get when I tell people what I’m studying. As a professional writing major, I’ve done journalism and PR writing, but I’ve been most drawn to technical writing.

Why? I had not given it much thought. Most people think of technical writing as boring or tedious. So why pursue it? What really drives technical writers?

As I’ve thought about these questions and talked to technical and other professional writers who’ve been at it much longer than I, I’ve gleaned a few potential answers.

- It’s useful. Some people find a lot of satisfaction in their ability to help others understand things. They feel they are making a difference.

- It’s necessary. Technical manuals may not always be read by customers, but they are a necessary step in the process of distributing the product. There is satisfaction in contributing to a company’s success.

- It’s interesting. For people who are naturally curious, technical writing offers an ideal situation: learn about new ideas and products, and get paid for writing about them.

- It’s lucrative. Yes, some people are just looking for something that pays the bills.

All of these are valid reasons to do technical writing. However, none of them really expresses my motivation (although the last one is starting to look pretty good when I think about my student loans).

I’m pursuing technical writing because I genuinely enjoy it. I like creating an organized, easy-to-follow document. I like figuring out how to use words effectively and concisely. I’m a bit of a perfectionist and don’t mind spending time on “minor” details. I suppose I enjoy learning about new things or knowing that I’m helping others, but ultimately, it’s a way to do what I love.

Maybe this makes me the exception among technical writers, but I hope not. Technical writing isn’t for everyone, but for those of us who enjoy it, it can be just as satisfying as any other career.

###

Image credit: George Brettingham Sowerby via OBI Scrapbook Blog

College Majors to Avoid + Rebuttal

And back to the work itself

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Yesterday I found myself in disagreement with the Burnt-Out Adjunct (whose too-infrequent posts I eagerly await and enjoy) who wrote that liberal arts studies should be more corollary than central to a college degree. Pisspoorprof was reflecting on another of these “ten worst” articles that pop up from time to time. This time it was Yahoo! Education touting the Four Foolish Majors to Avoid if you are trying to reboot your career.

Liberal arts degrees were the #1 opportunity killer with philosophy a close #2 opportunity killer. By the way, I cannot help but note that the entire article is an advertisement for the continuing services of Yahoo! Education.

As a holder of an undergrad degree in philosophy I both agree and disagree.

- Yes: no one hires a college grad to resolve deep-seated teleology questions (one does that on one’s own time). But to his credit, the VP at Honeywell who gave the OK to hire me (lo these many years ago) did question my stance on freedom vs. determinism.

- No: How about granting a bit of perspective? We need people who can think outside the present job parameters. And we desperately need people to challenge those parameters. Educating people to acquiesce by default is not what we need (though it is a short-term path to cash). Liberal Arts (and especially philosophy, let me say) can help this happen. Yes that sounds like the standard line from any college admissions staff says. Yes it is what professors say as they pass each other in the hallowed halls. No you don’t need a college degree to challenge the system, make a million bucks, make a difference or be homeless.

But studying things that don’t make money has a way of making us more conscious of all that is going on around us. Will it eventually make money? Maybe. Maybe not. But we need people with larger vision who can paint or write or photograph or build a different way of looking at things—however that happens.

What do you think?

###

Image credit: Studio Lindfors via 2headedsnake