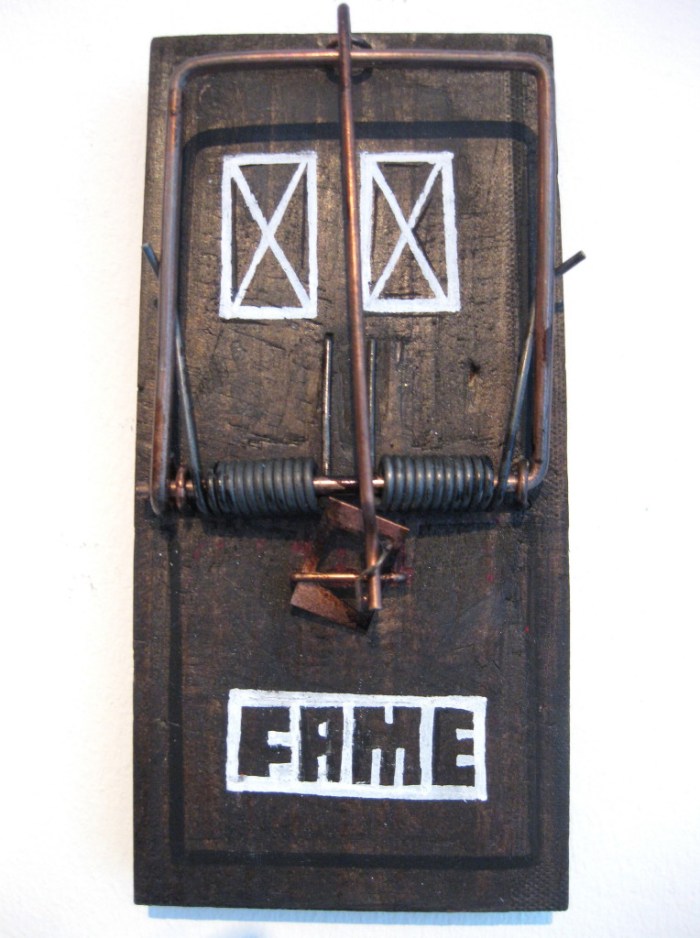

Do a Dumb Sketch Today

Magnetize Eyeballs with Your Dumb Sketch

As a copywriter, I’ve always prefaced my art or design-related comments with, “I’m no designer, but….” I read a number of design blogs because the discipline fascinates me and I hope for a happy marriage between my words and their graphical setting as they set off into the world.

As a copywriter, I’ve always prefaced my art or design-related comments with, “I’m no designer, but….” I read a number of design blogs because the discipline fascinates me and I hope for a happy marriage between my words and their graphical setting as they set off into the world.

But artists and designers don’t own art. And I’m starting to wonder why I accede such authority to experts. Mind you, I’m no expert, but just like in the best, most engaged conversations, something sorta magical happens in a dumb sketch. Sometimes words shivering alone on a white page just don’t cut it. Especially when they gang up in dozens and scores and crowd onto a PowerPoint slide in an attempt to muscle their way into a client’s or colleague’s consciousness. Sometimes my words lack immediacy. Sometimes they don’t punch people in the gut like I want them to.

A dumb sketch can do what words cannot.

I’ve come to enjoy sketching lately. Not because I’m a good artist (I’m not). Not because I have a knack for capturing things on paper. I don’t. I like sketching for two reasons:

- Drawing a sketch uses an entirely different part of my brain. Or so it seems. The blank page with a pencil and an idea of a drawing is very different from a blank page and an idea soon to be fitted with a set of words. Sketching seems inherently more fun than writing (remember, I write for a living, so I’m completely in love with words, too). Sketching feels like playing. That sense of play has a way of working itself out—even for as bad an artist as I am. It’s that sense of play that brings along the second reason to sketch.

- Sketches are unparalleled communication tools. It’s true. Talking about a picture with someone is far more interesting than sitting and watching someone read a sentence. Which is boring. Even a very bad sketch, presented to a table of colleagues or clients, can make people laugh and so serve to lighten the mood. Even the worst sketches carry an emotional tinge. People love to see sketches. Even obstinate, ornery colleagues are drawn into the intent of the sketch, so much so that their minds begin filling in the blanks (without them realizing!) and so are drawn into what was supposed to happen with the drawing. The mind cannot help but fill in the blanks.

The best part of a dumb sketch is what happens when it is shown to a group. In a recent client meeting I pulled out my dumb sketches to make a particular point about how this product should be positioned in the market. I could not quite hear it, but I had the sense of a collective sigh around the conference table as they saw pictures rather than yet another wordy PowerPoint slide. In fact, contrary to the forced attention a wordy PowerPoint slide demands, my sketch pulled people in with a magnetism. Even though ugly, it still pulled. Amazing.

###

(I rarely fish, but…) Angling Life: a Fisherman Reflects on Success, Failure and the Ultimate Catch (Review)

Angling Life is a long conversation

[Full disclosure: Captain Dan Keating is my cousin. He asked me to review his story, which I am happy to do.]

Angling Life is a long conversation. The kind you have spending hours in a boat waiting for fish to bite. The kind that ranges from food to the stupid stuff you did as a kid to watching your own kids grow–that is, everything. But Angling Life is also a journey book: one man’s quest for the perfect fish—or at least the perfect fishing conditions. As such, this conversation stretches across the globe and occasionally strikes at realities swimming deep inside any man. It’s this search for the best fishing that organizes Captain Dan’s reflections.

For years Captain Dan has run a charter fishing business on Lake Michigan. He is a fisherman who has made a business of fishing, writing about fishing in books and regular columns as well as holding fishing seminars. Most summer mornings he’s up early with groups eager to get out on the big lake to catch whatever is running. Sometimes the groups know what they are doing. Often they don’t. Captain Dan runs interference on his well-equipped boat so his clients have a great time and catch fish. He has always had a sixth sense about where fish are and how to catch them. Electronics help, but his fishing instinct may exert even more pull. Angling Life tells stories of the failures and successes where this instinct has led—and how the instinct has changed as well over time.

For years Captain Dan has run a charter fishing business on Lake Michigan. He is a fisherman who has made a business of fishing, writing about fishing in books and regular columns as well as holding fishing seminars. Most summer mornings he’s up early with groups eager to get out on the big lake to catch whatever is running. Sometimes the groups know what they are doing. Often they don’t. Captain Dan runs interference on his well-equipped boat so his clients have a great time and catch fish. He has always had a sixth sense about where fish are and how to catch them. Electronics help, but his fishing instinct may exert even more pull. Angling Life tells stories of the failures and successes where this instinct has led—and how the instinct has changed as well over time.

Captain Dan’s personal journey stretches across the globe over the course of this conversation. Each story takes the reader to a different, often far-flung setting, where a fishing story frames Captain Dan’s own questions. There’s fishing in Iowa and Minnesota, fishing in the Rockies, the Atlantic and Pacific, off Cabos San Lucas and Bali and, of course, Lake Michigan. Bait, depth, boats, waves—honestly, I’m not much of a fisher-person but there is much to commend Angling Life because Danny tells details which fill out each story. Details about being a charter boat captain and the business that surrounds that position. Details about storms at sea, and storms inside, about looking for a sure footing everywhere, except for the foundational places he heard about growing up. Which is the place he eventually returned. Captain Dan’s prodigal story is the central story. Like many prodigal stories, it is the inevitable decline that prods him to make life changes. Captain Dan’s journey points to God and the Christ of God—but not in any churchy way you’ve ever heard before. The conversation between writer and reader ultimately invites relation with God, but like two deckhands talking about work-a-day tools of everyday life.

The chapters stand as individual stories, which is a strength. But I might have hoped to see the chapters fit together into a longer learning-narrative with a cohesive story line running the length of the book. Because I know Dan, I found myself itching to hear even more details about the internal storms: to name names. To confess sins. To point out the cause and effect that motivated his seeking and eventual finding of the biggest fish.

###

Jeff Jarvis: “When I was the Goulish Gawker”

Great story by Jeff Jarvis about when he covered the last royal wedding. I love the gritty details about how the paper-bound press ran.

Say More About That: Why one Bible writer stopped his story nearly mid-sentence and why it matters

Leaving a reader with less than they want is akin to walking off stage in the middle of your performance at the height of your fame. But the technique makes the story linger all the longer.

Last week a few of us finished working our way chapter by chapter through Mark’s story about Jesus the Son of God. We found the writing idiosyncratic. Intent on capturing action, the writer jumped from episode to episode, scene to scene. The writer seemed less interested in sermons or long speeches (hey—who is?) so just left them out (when compared to the other recorders of Jesus’ life). The writer also cast Jesus’ close followers in a mostly unflattering light: not really getting what Jesus was saying. Generally intent on their own interests—so much so that Mark’s abrupt ending—leaving the followers trembling, astonished and fleeing full of fear after they encounter the empty grave—is a sure sign they never really understood the whole thing. In other words, Jesus’ followers seem like real people. No plaster saints in this story.

We argued why the writer ended so quickly. Did he hear an ice cream truck and left his manuscript and never came back? Why would he miss the important stuff like Jesus rising to heaven in the clouds (which we know from the other writers)? Some of us wished he had included more.

I think the abrupt ending was purposeful. I think he meant to leave us with questions. I think he meant for us to look back into the story and ask what it means to wait and watch. And to ask what it means to believe. The story lives on because it seems so unresolved—especially the case of this walking-talking-breathing God-man.

In the areas I work in, we continually try to build avenues to say more. More about our product. More about our ideas. More about me. We constantly work to expand the time involved for me to talk and to convince you of something. We want to gain an audience with a physician, for instance, and keep her attention until she understands the benefits of our product. But not everybody does this. Some people are smart enough to stop. Garrison Keillor may well be one of them, having recently announced he will retire in a couple years, before someone taps him on the shoulder and asks him to think about what he will do next. The writer of Mark’s Gospel was another. There were others: Plato’s Protagoras chose to end a speech in precisely the same way, which left Socrates “…a long time entranced: I still kept looking at him, expecting that he would say something, and yearning to hear it.” (Mark Denya, Tyndale Bulletin: 57 no 1 2006, p 149-150).

When is it right to leave a story unresolved?

###

You Scare Me

Levinas Says Why

I’ve always felt the problem with others is they keep talking about themselves. It’s always what they need, what they want, what they think. Their opinion. There is far too little about me in what they say.

You might think I’m joking. I’m not. It’s what many of us truly think just under the surface and it hints we are not far from that three year old phase of shouting “Mine.” You know I’m speaking truth because you’ve thought the same thing: waiting for someone to stop talking so that you can voice what is important to you.

Emmanuel Levinas was another 20th century philosopher who knew something about finding people interesting. He penned his first book while in captivity in a Nazi prison camp. His imprisonment proved valuable in forming a set of thoughts that went a very different direction from what others were thinking. Levinas was concerned with what happens when we encounter the “Other.”

Levinas understood that the Other was outside of ourselves. Painfully obvious? Maybe not. We humans have this tendency to force every encounter through our grid of experience, our intent and, frankly, our ego. We too often reduce others to something that looks very much like us. So while we hear the person beside us talking, we may pick up only on the words they say that affect us and miss the words that don’t affect us. We may routinely miss the words that oppose our intent along with the ones that describe the passion of this other person. Anyone with an old married couple in their lives has had first-hand experience with the practice of selective hearing.

“Wait,” you may say. “I’m a people person. I love being with others. Surely I have no natural aversion to others?” But Levinas pointed well beyond personality concepts like introversion/extroversion. He pointed beyond the contexts that inform our relationships: how we respond differently if the person before me is a subordinate or a boss, someone from the executive suite or a lowly clerk who can (should?) wait while I finish my dinner before I deign to speak with him. You can perhaps see the problem: how we interact, how we even think of the person before us—whether we even see the person before us—all is rooted in our context. It is rooted in how we perceive ourselves in culture, how we understand our position and our role. Standing is a very encultured episode.

Levinas invites us to strip away these contexts and come face to face with another. You’ve already had encounters like this, where context has been entirely scrubbed clean. Maybe you were at a party and met someone who later you found out was “Someone.” But during your chat you treated him or her like any other schlep.

How we deal with others, what we expect from our interactions, how often we assume others thinks like us and/or read that into our interactions—all these instinctual reactions limit our listentalk. Maybe they even derail our listentalk.

Listentalk means embracing the notion that others around us have much to contribute. And possibly that others are integral in helping us become the humans we were want to be. Levinas also awakens the very faint hunger in all of us to hear from The Other—God. And listening to God is a crucial piece of successful listentalk.

###

Steve Jobs: “…you have to trust the dots will connect in your future.”

File Under “Memorable Speeches”

Check out Steve Jobs speaking at a Stanford graduation in 2005. Favorite moment (~5:35): “You can’t connect the dots looking forward. You can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will connect in your future.”

Thanks to Bob Collins at MPR News Cut for the link.

###

What Didn’t You See Today?

Giant Metal Men Matter

Have you noticed the gigantic metal men standing in your neighborhood? One’s over there, just above the tree line. Enormous and sinister. Sort of hulking at around 100 ft. tall. What’s that–you’ve not noticed it? How could you miss it, standing there in the wide open? Your kids saw it and have already made up stories about it: why it’s there and how it could reach down and grab anybody at any moment so let’s not spend too much time beneath it.

Electrical pylons are just one of the things we miss as we walk or drive around our city. They only become visible when someone shows you. Then you see them. Your eyes probably registered the shape and presence, but somehow the tall tower did not enter your consciousness. You needed someone to point it out—not that you particularly care about pylons. Same with people: do we even notice the janitor cleaning the corridor at the airport or the clerk at the grocery store? We are trained to have these people blend into the background, just like the pylons. Just like the homeless guy at the stop light on Hennepin and Lyndale. It makes our life easier—less to deal with—when we don’t see these things or people.

How much we are missing when we tune out stuff we don’t want to deal with?

One of my clients is trying to help a particular set of physicians tune in to a class of patients that are largely unstudied. These patients present with certain features in their heart that routinely exclude them from pharmaceutical and other clinical trials. The conventional wisdom is that the outcomes would be significantly worse if these patients were included. So they aren’t. It’s a kind of research Catch-22.

My challenge this week is how to help these physicians see these patients. These patients cannot be treated until they are seen. Which is true for all the invisible stuff in our lives: we can’t deal with it as long as it is out of sight.

More on pylon appreciation: Alain de Botton from The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work.

###

TOC 2011: Margaret Atwood, “The Publishing Pie: An Author’s View”

This is worth watching.

“…transcribing whores for their pimp brains….”

The Author of Unremitting Failure is Failing at Failing

I cannot get enough of Unremitting Failure. Who is this person so bent on failing he (she?) succeeds so spectacularly with every post? My favorite line:

I cannot get enough of Unremitting Failure. Who is this person so bent on failing he (she?) succeeds so spectacularly with every post? My favorite line:

“It is perhaps true that some people write what they think, but we hold such people in contempt. They’re merely transcribing whores for their pimp brains as they turn out scholarly treatises, op ed pieces and the like.”

###