Why So Distracted? Distraction by Damon Young

Thanks!

Any shiny bauble catches my eye.

Any bare wisp of an idea pulls me from a thought-intensive task.

Is there a book I’ve not read? Let me order it right now, in the middle of this sentence.

I am easily distracted.

I am not alone in this.

I recently had the distinct joy of slowly reading Distraction by Damon Young. I followed Mortimer Adler’s advice in his lovely How To Read a Book (I should reread that—let me order it right now), which often leads to relaxed hours of thoughtful graffiti in a bound book.

I’ve written about Mr. Young’s book before, like here and here. But now that I’ve gone through it a second time, made annotations, outlined his argument, tweeted the author (twice) (now thrice), ordered half a dozen of his suggested books and quibbled about and finally recommended it to friends and family, I need to look at my own patterns of distraction before disengaging from the book’s orbit.

First: Mr. Young did a good job explaining why it is we are easily distracted and, in fact, why seek out distractions. The short answer is that we seem to recoil from our life purpose. As free people we choose where we spend our time (or at least how we spend our otium). We can spend it sorting out our life purpose. Or not. But we have to know our life purpose. And that takes work, which is why distractions are often so preferred to focus.

The longer answer is to look at the smart and thoughtful writers, poets and artists Mr. Young researched to see how they were distracted and how they attempted to focus. His stories brought to life Heidegger, T.S. Eliot, Nietzsche, Matisse and Henry James and many others (especially Plato). That’s why Distraction is fun to read (are stories always magnetic?)

Second: toward the end, Mr. Young cites the notion of gratefulness. That set me to wondering whether thanks needs a being at the other end. Young, a [critical but] sympathetic atheist, pointed to giving thanks as a primary building block for the undistracted life. But not the thanks of the poor to the benefactor for relief from a low condition. Instead:

…there is a primordial, anonymous gratitude, not to a patron or a savior but for the simple fact of existence itself. If we cannot choose our birth, or vault the impermeable barriers of place and time, we can still warm to the existential endeavor; we can smile at the opportunity to live, instead of flinching or close our eyes.

Thanks, for Mr. Young, is a bold “Yes!” to all the stuff of life:

But at its most profound, this is a simple, primal yes: to the attempt, the aspiration, the lurch towards freedom. To seek emancipation from distraction is to accept this ambivalent liberty – an unspoken, unrepentant thank you for the adventure of becoming. (160)

But is there such a thing as “anonymous gratitude”?

Maybe: friends have thanked the universe for bestowing good fortune on them. And certainly developing a generally grateful attitude to the stuff of life makes rational sense. But for me “thanks” minus the Almighty is like leaving Minneapolis intending to drive to Des Moines but finding yourself living for decades in Ankeny without ever having reached Des Moines (surely you know the splendors of Des Moines, Iowa).

But that’s just me. I greatly respect Mr. Young’s marvelous book and I agree that thankfulness opens the quintessential way of living. Thankfulness puts all other things in perspective, which is the essence of focus.

###

Image credit: Robert Huber via MPD

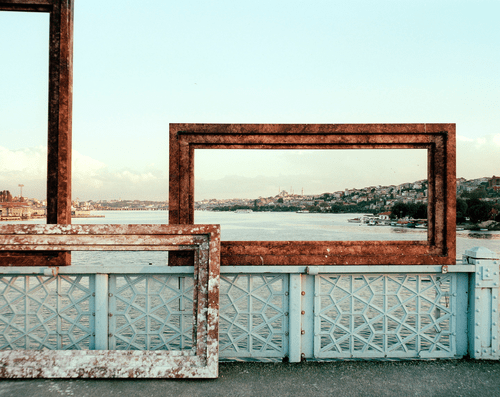

Travel Theme: Connections

Sometimes a slight change in plane determines where the rain hits, which makes a connection between wet glass and dry. Whether you stay in or go out. Between pessimism and optimism.

I’ve been watching different photographers respond to Where’s my backpack and thought this represents a kind of connection.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Corporate Voice Meet Shiny Plastic Food Tray

“No, you know what, screw it, we love it man.”

Recent conversations set me to thinking about corporate voice. Clients uniformly want to be heard with bold authority but then the lawyers and regulators find the [fresh/spicy/freaky] copy and emasculate it with sharp strokes.

But let’s not just point at lawyers and regulators, let’s admit that bold is a dangerous position. Bold words might fail. Or be seen as stupid. Bold words may pin me to a promise: uncomfortable!

Voice has always taken courage. Being heard has always been a risky endeavor. Especially when what you have to say goes against the grain. Think Elijah calling fire from the heavens. Think John the Baptist nailing the authorities as vipers. Think Richard Branson. That’s right: He of the airlines and music and phones and whatever else his Virgin Group encompasses. He of the bold statements. Maybe Sir Richard Branson is no Elijah or John the Baptist, but his company did produce this airline tray mat, which is at least a tiny voice crying in the wilderness of corporate voice.

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

It’s Better to Have the Conversation Than Not

Assumptions are a cul-de-sac. Admissions, an autobahn.

A fast-moving project I’m on pits the changing need of the client with the frantic response of the agency. I’m writing copy and providing strategic direction for a moving target, which has (literally) kept me up nights.

One truth that has proven itself to me several times over the past few weeks is that it is simply better to have a conversation than to not. That may seem obvious to you. But it’s taken me years to come to understand this. I’m too easily put off by the gruff manner or the fly-off-the-handle personality. It’s too tempting to put my head down and just do the work. But the way forward—especially when the task and deliverables are murky—is to talk together about what we understand. Naturally it is embarrassing to admit I know only this much (thumb and forefinger stretched) when I imagine those who wrote the scope of work know this much (from here to the wall, say).

But admit I must.

It is the only way forward. And sometimes it is the only way to get to the place where you can put your head down and do the work. Admitting what I know is also the best way forward: anything I can do to get the team on the same page, whether that means showing my rough draft copy or my quick dumb sketch of what I think the interactive designer just said. And by admitting what I know, others can feel free to admit what they know. That’s usually when I come to find out someone heading up the whole thing is just as baffled. But when we talk openly about what we know and especially what we don’t, a measured response can emerge and we assemble our next steps. At least until the next client meeting.

There is something of an art to getting people on the same page. Some personalities fall into this easier than others. Getting open discussion is aided by vulnerability: the admission. The confession. I suppose the question is: how badly do you want to move forward?

See also Seth Godin’s commentary about fearing the fear vs. feeling the fear. It may give you courage for your task.

###

Image Credit: Mark Brooks via 2headedsnake

(Please Write this Book) Busted, Berated & Celebrated: The Job for Anyone

Is Job the Michael Bluth of the Bible?

Now the story of a wealthy family who lost everything and the one [man] who had no choice but to, well…. It’s arrested development—with a twist: It’s Job’s tale, but with the focus shifted from his unjust suffering to a character trait everyone depended on.

He brokered peace for others.

Job had a habit of conciliating for his kids: after every round of feasting and drinking, he offered sacrifices, reasoning that just in case his kids cursed God, maybe his own intervention (which looked a lot like pleading) could help out. Just in case. This was Job’s habit.

And in the end, it worked. More on that in a moment

Would someone write this book? I want to read about how this habit of seeking help for others is more than just a pleasant idiosyncrasy of a hurting old man. Please unravel the mystery of this central piece of the story. I’d like know more about how Job’s habit of conciliation served as bookends to the entire story-with the Almighty making himself available (at least partly) because of Job’s habit. I’d like to read about how the right-sounding-but-flawed arguments delivered all the way through only reinforce how blinded we get in our self-righteousness. And how even the self-righteous need help in the end. I’d like someone to belabor the connection between what it means to care for others when you yourself are broken—wait, maybe Henri Nouwen already wrote that.

Please write Busted, Berated & Celebrated: The Job For Anyone.

I’ll read it.

I may even buy it.

###

Image credit: Wikipedia