Posts Tagged ‘philosophy’

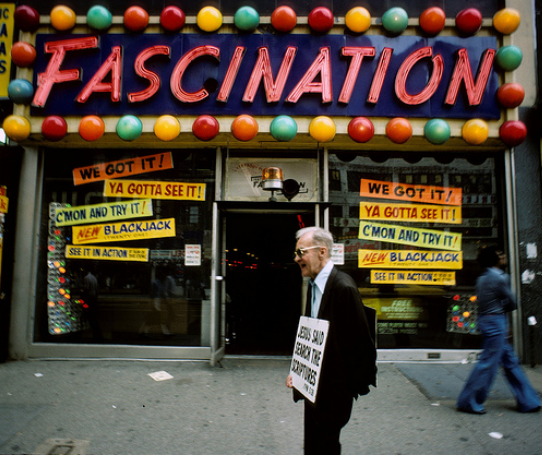

Philosophers Make Uncomfortable Pastors

Sermons built on questions only inflame the faithful

It’s the philosopher’s job to ask uncomfortable questions. They don’t take ideology as a given. They question ideology—that is forever the philosophical task. Some philosophers reading this would say “Yes, and what do you mean by ‘pastor’ and who/what is ‘God’”? That’s fair and a reasonable line of questioning. Certainly worth examining.

It’s the philosopher’s job to ask uncomfortable questions. They don’t take ideology as a given. They question ideology—that is forever the philosophical task. Some philosophers reading this would say “Yes, and what do you mean by ‘pastor’ and who/what is ‘God’”? That’s fair and a reasonable line of questioning. Certainly worth examining.

But say a philosopher has satisfied herself there is a God. And say that philosopher has a commitment to the God revealed in the Bible (yes there are such people). Can she pastor others? Can he serve as a shepherd? Can she speak sermons that have questions rather than answers?

No. At least not to our typical congregations. People come to church for comfort and to be told they are going the right direction. To offer the food of questions is to deny parishioners the happy holy feeling they paid for when the offering plate passed by.

But honestly, can a pastor be anything less than a philosopher? Because the claims of Jesus (to start there, for instance) are so wildly outlandish as to call into question the threads of daily existence. For instance, this notion of turning the other cheek to the one who just slapped you—it’s completely nutty stuff. Unless it is actually meant to be worked out in daily life. Unless it says something crazy deep about each and every interaction we have. To treat Jesus’ words as ideology only—as some exalted religious state—and to not examine them further in the crucible of daily life is step forward with 75% of your brain shut off.

And that’s no good. That’s no way to live.

It’s also true that most philosophers don’t abide the preacher’s art of packaging things in tidy simple packages that are easily understood. Questions don’t often fit those boxes: they bump against corners and lids with their labored back story and brief histories of how others have asked them. That’s tedious stuff that rarely fits into three alliterative points.

Which is not to say philosophers should not pay attention to packing their thoughts so they become mind-ready. They should and many do. But philosophers mostly cannot escape the orbit of the questions themselves.

I think philosophers don’t make good pastors. But I hope to stumble on such a being at some point in my existence.

###

Image credit: 4tones via 2headedsnake

Talking Philosophy with a 10-Year Old

Why not talk about something more interesting like dragons or flying?

I like reading Emmanuel Levinas. He’s mostly opaque, but every once in a while his writing opens on a breathtaking view and is just what I needed. If I had the opportunity to explain why Levinas matters to an interested ten-year old, I would say that we have a problem with other people. And the problem is that we mostly don’t want to hear from them. I could use an example from their life: you don’t want your mom to interrupt your fun: when she calls you in for dinner, you go in only reluctantly. One problem with the will of the other is that we don’t welcome distraction from our preoccupations. But it is not just that, it is that we really don’t want to even interact with some other who might have authority over us.

I like reading Emmanuel Levinas. He’s mostly opaque, but every once in a while his writing opens on a breathtaking view and is just what I needed. If I had the opportunity to explain why Levinas matters to an interested ten-year old, I would say that we have a problem with other people. And the problem is that we mostly don’t want to hear from them. I could use an example from their life: you don’t want your mom to interrupt your fun: when she calls you in for dinner, you go in only reluctantly. One problem with the will of the other is that we don’t welcome distraction from our preoccupations. But it is not just that, it is that we really don’t want to even interact with some other who might have authority over us.

10-Year-Old: “Oh. You just don’t want to do what other people say. Does Levinas tell you how to avoid doing what others tell you to do?”

Kirkistan: “Not exactly.”

10-Year-Old: “Does he tell you don’t have to do what they say?”

Kirkistan: “No. It’s more like you suddenly want to do what the other person wanted because you really, really loved them.”

10-Year-Old: “Like maybe if my grandparents were in town and asked me for something and I wanted to do it for them because they are so nice?”

Kirkistan: “Yeah. Maybe like that. And maybe you found yourself really interested in the experiences they had, partly because they are such good storytellers and they make everything sound so exciting. You like their stories and can almost imagine being there.”

10-Year-Old: “So my grandparents are cool and I want to get to know them because they are nice and tell interesting stories. So what you are really talking about is why it is important to hear from other people and why we should care.”

Kirkistan: “That’s right.”

10-Year-Old: “So why did you start be talking about stopping what I thought was fun to do something I had to do?”

Kirkistan: “Well, I might have been a bit confused. But also because sometimes I close my ears to people who are trying to give me a gift. Something I really need. Say you are at the grocery store with your parents. It’s Saturday. And there are sample ladies on every aisle. There is lady offering free ice cream in the frozen aisle. And another man making pizzas in that aisle. And another with little chicken nuggets and another handing out crackers and cheese.

Kirkistan: “But say you really didn’t want to go to the grocer. You really wanted to watch cartoons. So you went to the grocer reluctantly, but you took your iPod and listened to music the whole time. You walked behind you parents, music turned up. So you didn’t hear the sample ladies calling out to you. You kept your eyes on the floor so you didn’t see them either.”

10-Year-Old: “That would be bad. I like ice cream and chicken nuggets and pizza. It’s like I had missed all the really good stuff while everybody else got something. I’d have gotten my way but I’d have missed out on the very best stuff.”

Kirkistan: “That’s why Levinas is important. He helps us start to see and understand why it is we should care about the people around us: what they know. What they bring to our conversations. What they have to say about this and that. Even people who don’t seem to have anything to say—even those people can surprise us with lots of interesting things.”

10-Year-Old: “OK. Well, why don’t you just listen to people? I listen to people and learn things all the time. That isn’t hard to do. It is super easy to listen to people. It’s not like you have to do anything. You just listen.”

Kirkistan: “Well, that is great advice and I want to follow it. My answer to you would be that as you get older, you start to think you know a few things. We get to thinking we know the patterns of how things work and we figure we know pretty much how anyone will respond in any given situation. Anyway, all I’m saying is that it gets pretty easy to think you know what most people will do or say in any given situation. The surprise—if you can call it that—is that quite often people live up to our expectations. They do what we think they’ll do. Not always. But often. Then the question becomes, “Did that guy say that because I expected him to say it?” “Did I have a hand in turning this conversation this way?”

10-Year-Old: “You’re pretty boring aren’t you?”

Kirkistan: “You might be right.”

10-Year-Old: “Why don’t you write about something interesting like dragons or warships? Why don’t you write a book about how to fly?”

Kirkistan: “Great suggestions. I really want to write a book about how to fly. I think that this is the book I am writing.”

###

Image Credit: Mid-Century via thisisnthappiness

Is it Time You Wrote Your Autobiography?

I’m not writing one. Then again, who isn’t adding to their autobiographical material daily, whether with words or deeds?

I’ve been reading the autobiography of R.G Collingwood, an Oxford philosophy professor of the last century. He set out to trace the outline of how he came to think—a kind of personal intellectual history. Early on in his life (at 8 years old) he found himself sitting with a philosophy text (Kant’s Theory of Ethics). And while he did not understand it, he felt an intense excitement as he read it. “I felt that things of the highest importance were being said about matters of the utmost urgency: things which at all costs I must understand.” (3) That reading set one course for his life.

One thing that makes this book worth reading is his notion of how questions and answers frame our production of knowledge. Collingwood said he “revolted against the current logical theories.” (30) He rebelled against the tyranny of propositions, judgments and statements as basic units of knowledge. He thought that you cannot come to understand what another person means by simply studying his or her spoken or written words. Instead, you need to know what question that person was asking. Because what that person speaks or writes will be directly related to the question she or he has in mind. This is incredibly useful when studying ancient texts—like a letter from the Apostle Paul, for instance. It’s also incredibly useful when listening to one’s wife (ahem), or a student or to anyone we come in contact with.

Another thing that recommends this book is hearing him tell about his main hobby: archaeology. Collingwood was the opposite of a couch potato. He spent a lot of times in digs around the UK, unearthing old Roman structures and then writing about them. Here too, he explained that while some archaeologists just set out to dig, he only set out to dig when he had formed a precise question to answer. His digging (tools, methods, approach) were all shaped by this question. By starting with a question, he came to very specific answers and, of course, other brand new questions.

Questions begat answers. And more questions.

What question is your life answering?

###

Image credit: J-J. Grandville via OBI Scrapbook Blog