Archive for the ‘art and work’ Category

No, Really: What does a Philosopher do?

When Adjuncts Escape

Helen De Cruz has done a fascinating and very readable series of blog posts (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) tracking the migration of philosophical thinking from academia into the rest of life. As low-paid, temporary workers (that is, “contingent faculty” or “adjuncts”) take over more and more university teaching duties (50% of all faculty hold part-time appointments); smart, degreed people are also starting to find their way out of this system that rewards increasingly narrowed focus with low pay and a kick in the butt at the end of the semester.

Ms. De Cruz has a number of excellent interactions with her sample of former academics (at least one of whom left a tenured position!). I love that Ms. De Cruz named transferable skills. What would a philosophy Ph.D. bring to a start-up? Or a tech position? The answers she arrives at may surprise you.

I’ve always felt we carry our interests and passions and skills with us, from this class to that job to this project to that collaboration. And thus we form a life of work. Possibly we produce a body of work. We once called this a “career,” but that word has overtones of climbing some institutional ladder. I think we’re starting to see more willingness to make your own way—much like Seth Godin described his 30 years of projects.

The notion of “career” is very much in flux.

And that is a good thing.

Of particular interest to me was the discussion Ms. De Cruz had with Eric Kaplan. Mr. Kaplan found his way out of studying phenomenology (and philosophy of language with advisor John Searle!) at Columbia and UC Berkeley to writing television comedy (Letterman, Flight of the Conchords, and Big Bang Theory, among others). If you’ve watched any of these, it’s likely you’ve witnessed some of the things a philosophical bent does out loud: ask obvious questions and produce not-so-obvious answers. And that’s when the funny starts. It’s this hidden machinery that will drive the really interesting stuff in a number of industries.

Our colleges and universities are beginning to do an excellent job dispersing talent. That thoughtful diaspora will only grow as time pitches forward.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

“Good to Know” and a Failure to Communicate (DGtC#23)

I’ve said too much already.

If you hear this, you’ve said too much. You’ve said more than someone wanted to hear. “Good to know” is a polite way for your listener to indicate, “Please. Shut it.”

Why do we say too much?

Maybe we are excited about a topic. People will often have mercy with this motive. Sometimes the excitement rubs off. Our favorite professors and speakers demonstrated their enthusiasm for a topic by going on. And on.

Maybe it is a nervous tic that flows from fear of awkward silence.

Maybe we are hiding our tracks, like the alcoholic filling up verbal space to avoid the obvious question. Maybe our rush of words is like throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks, to throw our interrogators off our track.

Maybe we’re signaling dominance. Stringing together buzzwords at a rapid pace is a time-honored tactic in corporate meetings where you have no clue how to respond. The tactic usually ends in promotion because higher-ups read “kindred spirit” in your fast mumbling. Maybe our club or church or group listens for key words to show who is in and who is out, so our rush of words is a frantic attempt to show we are in.

“Good to know” is a proper, dismissive response to much of the advertising done to us: superfluous, out of step with regular life and an obvious pitch for our pocketbook.

But when we hear “Good to know,” it may be worth stepping back and getting momentarily meta, and thinking, “Oops. I might have misjudged this person’s interest. How can I get back to connection?”

Connection is the place to be. Connection gets along well with enthusiasm and does not mind probing into track-hiding. But connection does not abide dominance.

See also: How be a verbal philanthropist (#14)

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Cure for the Common Blahs (Millman + Godin)

Take Two Books and Call Me In a Week

I’ve been reading Seth Godin’s The Icarus Deception (NY: Penguin Books, 2012) and Debbie Millman’s How to Think Like a Great Graphic Designer (NY: Allworth Press, 2007). Both books convey hope that work can look different—more personal and more meaningful—than any corporate recruiting brochure can ever let on.

Mr. Godin’s message is consistent with his blog and other books: find a way to not submit to corporate overlords and their pre-packaged (wonderful) plan for your life. Make your own way. Along the way he hints that owning your work can happen in a variety of ways (even if working for the man). I’ve always appreciated Mr. Godin’s sense that art is about making connections and doing new things that spring from one’s brain/desire/compulsions/passions applied to a real-world problem. I would argue that kind of passionate living can happen in a big company or on your own—but we must all keep a sharp eye out for when life and work become rote ruts (which require re-routing).

Ms. Millman’s book is an absolute delight to read because it consists of 20 conversations with designers whose work has set them apart for years. People like Stefan Sagmeister, Neville Brody, Paula Scher, Emily Oberman, Bonnie Siegler, Paul Sahre, James Victore, Massimo Vignelli and Milton Glaser. The genius of  Ms. Millman’s book is two-fold: asking penetrating, questions (1) and then standing aside (2) to let each designer spool out their answers in the way they choose. I’m certain each question and answer was edited, but Ms. Millman’s book gives a sense of hearing the very crux of what drives each person’s creativity in their own words. Their answers provide lessons in the habits of artists, how to combat the woo of popularity and the lapses into isolation. Some of these designers have succeeded and failed and succeeded and failed—so look also for lessons in starting over from scratch.

Ms. Millman’s book is two-fold: asking penetrating, questions (1) and then standing aside (2) to let each designer spool out their answers in the way they choose. I’m certain each question and answer was edited, but Ms. Millman’s book gives a sense of hearing the very crux of what drives each person’s creativity in their own words. Their answers provide lessons in the habits of artists, how to combat the woo of popularity and the lapses into isolation. Some of these designers have succeeded and failed and succeeded and failed—so look also for lessons in starting over from scratch.

I’m no graphic designer—maybe you aren’t either.

And I’m no artist (perhaps you are?), but Godin + Millman together provide a satisfying set of snapshots that keep anticipating the very personal work your problem-solving can accomplish. The advice and hope from each book make me want to look for problems to work on that take advantage of what I love doing.

Both books present forward-looking ways of relentlessly defining, redefining and doing your own work. And make no mistake: again and again it is the work itself that pulls these talented people deeper into their talent and continued relevance.

What is your work today?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

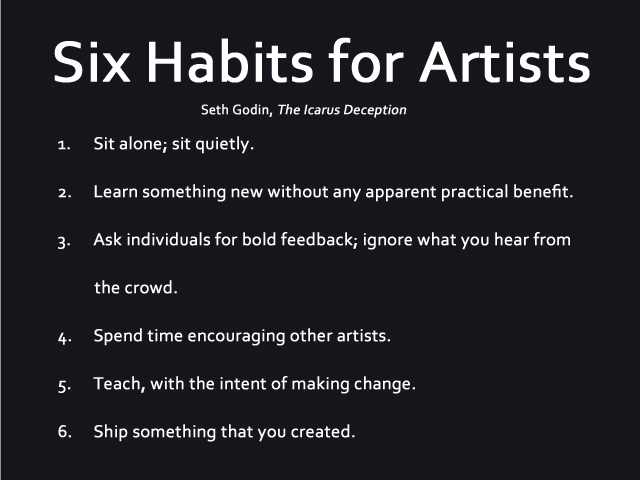

Seth Godin: Six Habits for Artists

Especially #6: Ship it.

I like Mr. Godin’s expansion of “artist” to include anyone trying to make a connection (full definition here). If you are trying to create, you’ll find these six habits useful.

###

Should You Make Your Boss Cry?

Just draw me a picture

In a conversation yesterday my new friend self-identified as one who enjoys the “messy work” of helping groups get on the same page. To that I say: may her tribe grow. Because that is messy work indeed—fraught with bruised egos, sullen colleagues and cross-purposed tasks.

I maintain there is a fair amount of artistry involved in helping a group begin to move forward. Those who help others catch a vision for a project or cause have a knack for painting pictures. These pictures help team-mates understand just what is at stake. Those pictures may be dumb sketches or verbal images. The word “picture” here is important because an image conveys emotive content often missing with words alone. Without the emotive content of a picture, we are back to just using our intellect. And intellect only carries us so far. We can know the reasons behind a purpose, walk through spreadsheets and examine data without ever getting our emotive selves involved.

For many of us, real meaning has an emotional nexus. Pushing forward together springs quite naturally from that place where reason and care have linked arms.

The picture my new friend painted drew people from different business units in her organization—each armed with very different purposes and possibly their own rhetorical axes to grind—into a shared objective. The painting of the picture and telling of the story helped gradually align those cross-purposes.

What pictures are you sculpting for those around you today?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Team Leader As Artist: Let Your Team Crop Your Problem

What does your team see?

Photographers routinely crop and display just the section of the photo they want their audience to attend to. Cropping—possibly the easiest, most straightforward thing a photographer can do—changes the information the photo provides. Cropping also changes the feeling the viewer gets.

The right crop can stir emotion.

Most photographers work at getting composition right and so avoid cropping. Henri Cartier-Bresson famously accomplished that. Alec Soth gets this done too—though his process seems mysterious. The success of their composition looks like an invitation into another world, something frozen in time. Something clearly different from our own daily life.

That is the memorable artistry of the photographer.

Teams can be very gifted at cropping. Since we all naturally see a problem from a different perspective, collecting those perspectives in an open discussion can do a lot to reframe a problem into a most excellent opportunity. For a team to function this way, there needs to be a premium on open discussion. It helps if team-mates learn to value each other’s opinions. Listening and assigning value to each other’s contributions can be learned. I would argue it starts from the team leader (or manager/VP/CEO) and work its way down. Valuing each other’s perspectives (or not) is very much a part of corporate culture. But value can also move from the other direction: I’ve had teammates who valued different perspectives and taught the rest of us to find great joy in listening and considering.

Seth Godin routinely reframes art to include “making connections between people or ideas.” Some reading this will create art today by running a meeting that will make it possible for all around a conference table to hear a new thing. Their process for creating this art will be an examination of a problem that gets cropped from five or seven different perspectives. The result will be a well composed opportunity that has emotive power for each of the people at that table.

What art will you create today?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Northern Spark 2014: Don’t Freak

Go, by all means. Just don’t freak out…

…at the…

weird stuff.

Northern Spark: June 14 9:01pm – 5:26am, Minneapolis

Worth every minute.

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston

Your 10,000 Hours

Trust Your Process

There are times when you don’t know the answer and you cannot see a way to an answer.

There are times when you simply cannot see what to do next. This happens constantly in my work: even today I have a project that needs a unique kind of help. Help I cannot even quite imagine.

What to do?

My writing process seems to be all about working my way into a corner or a dead end. It happens again and again. But as I continue chipping away and working at it (which is to say, I keep writing), the dead end turns out to be a way to rethink something. Getting stuck in a corner turns out to be the necessary thing, the thing I needed to actually turn the corner.

Malcom Gladwell contends that you must put in 10,000 hours to become an expert at something. He may or may not be right about the numbers, but certainly an expert has worked out a process the she or he follows—some way they use to accomplish the thing they do. They’ve sorted some way to keep at it. And whether or not the outcome is perfect, the process itself is revealing.

That’s why one keeps at it: to see what the process reveals next.

What are your 10,000 hours revealing?

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston

Please Read Dave Eggers: The Circle

In a world where everyone sees everything…

If you’ve ever wondered where complete transparency might lead—as I have—consider reading Dave Eggers’ excellent novel The Circle.

Mr. Eggers has created a very comfortable world (for some) of deep collaboration, where everything is provided to those lucky enough to work for the Circle. The Circle, the corporation at the center of the story, looks more than a bit like our most celebrated high-tech companies brimming with smarts, cash and outsized ambition. Think Google or Apple or what Microsoft once was—and then add in a cast of characters each with an overweening and boundary-less high EQ—and you’ve got a world that is totally supportive—as long as you move in the same direction. The novel traces the story of Mae Holland as she “zings” (tweets) and “smiles” (likes) her way from outsider to the inner circle.

The story gets uncomfortable at times, especially when it shows the intent behind the use of social media and the social pressures applied. Especially when you start to recognize product placement on a very, very personal level.

Mr. Eggers has me rethinking my eagerness for employees up and down the corporate ladder to use their outside voice. I’ve been advocating, among my clients and when teaching Social Media Marketing, that helping employees reveal their work to interested outsiders is a move toward a new kind of marketing that looks less like selling and more like a conversation among interested parties. I still think that is a good move, but Mr. Eggers has explored the boundaries of that notion, and it is a bit, well, totalitarian.

I will consider using The Circle as a supplemental text for my next class on Social Media marketing. Well-written and consistently engaging, Mr. Eggers’ book is well worth your time.

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston, just before a recitation of photography rules within a non-public space

Why I Don’t Listen To Christian Music

Short Answer: No One Likes Being Manipulated

On Conversation is an Engine I mostly write about communication and conversation and copywriting and how business interacts because I am fascinated by what happens when people talk. But undergirding this sense of wonder is a faith in God that makes me see much of life in theological hues. The fallout from that theological saturation means I want to approach the work of communication and persuasion from an ethical perspective—as best I can.

Lots of music labeled “Christian” does not do that.

The college I occasionally teach at has a radio station that spins out Christian music. I stopped listening years ago when I realized my emotions were being manipulated by music that was nearly content-free. It had a veneer of faith, but seemed much more about living a good life and having positive feelings.

The college I occasionally teach at has a radio station that spins out Christian music. I stopped listening years ago when I realized my emotions were being manipulated by music that was nearly content-free. It had a veneer of faith, but seemed much more about living a good life and having positive feelings.

Especially positive feelings.

I’m not against positive feelings. Happy is good in my book. Happy makes sense to me. But if happy comes from a sugar-like high that dissipates as quickly as it formed, was it real? And is happy the point of faith in God?

I argue: No.

Happy is good. Joy is better and depending on how you define things, joy lasts longer. And true is best.

And really, what is Christian music? I might argue Tom Waits has a lot more truth to offer than whatever contemporary Christian band is currently famous. The Talking Heads seemed to provide many glimpses of truth—so do many of the folk musicians I listen to. Certainly Mr. Bach and Mr. Mozart and Mr. Telemann and Mr. John Adams and even Philip Glass provide more soaring and more depth and more truth.

Of course, music is a very personal thing and there is no right or wrong. We like what we like and I don’t want to disparage anyone’s choices—really I don’t. But if I sense I’m being manipulated by sentimental lyrics, I move on.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston, in response to on the move