Archive for the ‘Collaborate’ Category

What Business Can Learn From Church #2: Be Accountable—Especially After Conflict

Stop to Honestly Revisit Decisions

If everyone on your leadership team has an equal voice, how do you sort through conflicting opinions?

First, know that “equal voice” is as rare in teams as it is problematic. It’s likely some team members have a more equal voice—a voice that carries more authority (like the boss, for instance. Or the one who signs the bi-weekly pay stub). And, sadly, team-members willing to scream and throw a fit will often get their way through intimidation and/or sheer annoyance.

In this space between work, craft and carrying out community described yesterday, Seth McCoy talked about a leadership style that didn’t set the founding leader as the all-knowing, final-answer seer whose verdicts were solid gold. Instead, passionate committed leaders bellied up to give their opinions, expecting always to be heard. To continue to get full engagement from these leaders and their wide-open thoughts, team decisions must be revisited and discussed after the conflicting decisions.

Say your leadership team is conflicted on a pivotal decision. You need everyone behind the decision because you know each leader will motivate themselves and their teams based on the urgency of the task. You need them engaged. Whether your team takes formal votes on decisions or just gives a thumbs-up/thumbs-down, the mechanism that allows your leaders to respond to a decision should not be the final word. Allowing the team to revisit decisions in conversation builds trust—but those revisiting conversations must be open rather than defensive.

What business can learn from church is to build enough human to human accountability to actually, really, truly revisit group decision. To ask whether it works or not. And to offer honest assessments. And to build a solid history of honesty.

This is how any organization builds relational trust.

###

Image credit: gh-05-t via 2headedsnake

You may also be interested in:

18 HBR Finalists on Redistributing Power

It Is Written: The M-Prize and You

For some time I’ve wondered what leadership will look like when the power of monologue is finally revealed as the empty shell it always was.

For some time I’ve wondered what leadership will look like when the power of monologue is finally revealed as the empty shell it always was.

I’m not alone with that question.

It seems the folks running the Harvard Business Review have teamed with McKinsey to incent people to rethink “the work of leadership, redistributing power, and unleashing 21st century leadership skills.” The result is a series of case studies that should prove interesting—and not just to folks in the leadership industry.

I’ve not read any of these 18 articles but I plan on reading them all. I’m interested because the more we learn about how to build conversations that free our best thinking, the more likely we are to innovate. And the more likely we are to find ourselves living out our vocation. And the more that happens, the more better everything gets.

Yesterday I stumbled on an ancient text that presented an insight on the very kind of leader the M-Prize hopes to unearth. The text talked about a very unusual leadership skill set: This leader is equally at home encouraging the worker in pain as he is furthering the cause of justice. This leader can fan the dying embers of a person’s passion even as she moves earth’s largest causes forward. No trampling on others in an upward climb for this leader.

If you stop by Conversation is an Engine with any regularity, you know that a theology of conversation exerts a powerful gravity around here. We have this hunch that people were made to be in conversation and that we become fully human as we engage in conversation. And more: conversation may be a part of any knowledge we lay claim to.

Naturally, there’s a lot more to say about this.

But the leader who understands the power of conversation and works at interactive collaboration rather than straight-line order delivery is the leader poised to succeed.

It is written.

So—Kudos to the HBR/McKinsey folks for their vision.

###

Image credit: actegratuit via 2headedsnake

Are You a Philosopher or a Popularizer?

Must I choose?

In recent conversation with a local philosopher and food writer, we got to talking about the work of a philosopher in the world today. There’s teaching, which employs academic rigor to help students understand where philosophy has been and what it has been up to. There’s research, typically a subset of teaching, that sorts truth from fiction and sometimes swaps the two. And then there’s, well…that’s it. That’s what a philosopher does in our culture.

In recent conversation with a local philosopher and food writer, we got to talking about the work of a philosopher in the world today. There’s teaching, which employs academic rigor to help students understand where philosophy has been and what it has been up to. There’s research, typically a subset of teaching, that sorts truth from fiction and sometimes swaps the two. And then there’s, well…that’s it. That’s what a philosopher does in our culture.

Teaches.

Teaches rarified stuff only a few understand and even fewer care about.

Which is not to say philosophy is not happening all over the place.

I’ve begun to argue we’re all philosophizing all the time. We’re not all at the highly abstracted levels represented by academic philosophy. But we’re all in the business of making meaning. Most of us don’t much think about it: once we’ve figured out the basics of family and job and faith and community, the business of meaning-making largely runs on auto-pilot. Until we get cancer. Or age. Or lose a spouse.

Or see a sunrise.

The more questions we ask in everyday life—the less we take as a given—the more life we experience. This is the wonder of being amazed at the small connections that occupy those making meaning every day. Which should be all of us.

My recent conversation turned to the author Alain de Botton, who I described as a philosopher but then back pedaled. We allowed he was certainly a popularizer. I’m a fan of de Botton. I like the places his books send me and the meaning-making tasks he introduces. I also like to read Damon Young, the Australian who is a bona fide philosopher and card-carrying popularizer (meaning only that he regularly publishes philosophy columns in Australian newspapers).

I’m not sure so a philosopher cannot also be a popularizer.

I’ll argue my friend’s food writing displays a philosophical bent even as he courageously walks into the smallest, diviest joints in the metro. I’ll also argue that the ordinary conversations we have with each other, the ones where we try to sort out the details of life together, are themselves often instances of practicing a sort of popular philosophy.

Ordinary conversation is the very stuff of thinking together.

I hope it becomes more popular.

###

Image credit: Via 2headedsnake

Please Write This Book: How To Be Properly Peripheral

A word for the 99%

Not everyone can be at the center. Not everyone is the leader, the big cheese, the boss. Some dwell on the fringe. Work, neighborhoods, any given party, hey—even families have members who are more comfortable sidling toward the exit.

In these posts I’ve written that the church is better off not being in the center of things: we do better speaking in from the periphery. Give the church power and it behaves like anyone with power: making the rules and silencing the voices that disagree.

But purposefully peripheral? That’s a hard case to make in our culture, where fame is everything. Especially since most of us struggle with a mild solipsism: do you or your pet poodle or your Prius remain when I walk out of the frame? I’m not so sure. I only know what I know because I am at the center of everything.

Consider: the leadership industry devises all sorts of ways to help people pull themselves up by their own bootstraps so they become the center point, the pulpiteer for their organization. The respected voice, influencing others, perhaps (sinister hope) controlling others. That’s the favored spot—am I right?

But purposefully peripheral? There’s a pretty compelling theological argument for looking for ways to serve rather than control. Please write the book about how that argument unfolds for the 99% of us who are workers rather than rock stars. Please write about how our small daily actions have an impact. Please give me a vision for how the quiet, mostly unnoticed work is really the glue that holds society together and is also—quite possibly—the neurotransmitters of divine action. Tell me again why listening trumps talking most of the time.

I’d read that book.

I’d buy that book.

###

Image credit: Ed Fairburn via 2headedsnake

Juxtapose: How To Build a Church that Counters Culture

Theological Roots and Practical Hope for Extreme Listening and Honest Talk

Theological Roots and Practical Hope for Extreme Listening and Honest Talk

A couple nights ago Mrs. Kirkistan and I had dinner with old friends we’d not seen in some time. It was refreshing to catch up and there was lots of that free laughter that happens when old jokes and forgotten quirks reappear. At one point someone asked whether we were hopeful about the state of the evangelical church. We each offered an opinion.

Mine: “No.”

It’s actually a qualified “No”: my sense is that the evangelicalism has largely lost its way following industrial-strength, church-growth formulas and it has also sold its soul to political machinery. Following these tangents we’ve lost the essence of what it means to counter culture by speaking the words that stand outside of time.

I’m actually quite hopeful about what God is doing—especially in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area. We’ve seen a number of groups trying very new things while employing deeply-rooted devotion to sacred texts and veering from partisan nonsense. So my sense is that evangelicalism is morphing and, frankly (I hope) growing up.

For a couple years now I’ve been laying down about a thousand words a day toward this book dealing with the theological and philosophical roots of communication. It’s been a one-step-forward-seven-steps-back process. But I’ve just finished Chapter 8 and by the end of July I’ll deliver the manuscript to my editor friend. I’ll likely self-publish it later this year—I’ll probably have to pay people to read it (Know this: I cannot afford more than $5 a reader. So both of you readers give a call when you are ready. I’ll put a fresh Lincoln in the Preface.)

The book offers new ways to think about the ordinary interactions we have every day. It draws on a few philosophically-minded thinkers and reconsiders some old Bible stories to reframe the opportunity of conversation. It also provides a kick in the butt to move out of our familiar four walls to engage deeply with culture—but not from a standpoint of judgment, rather from a deep curiosity and love. I’ll be sharpening the marketing messages over the next few months, but here are the chapter titles so far:

- The Preacher, Farmer and Everybody Else

- Intent Changes How We Act Together

- How to be with the God Intent on Reunion

- Your Church as a Conversation Factory

- Extreme Listening

- A Guide to Honest Talk

- Prayer Informs Listening and Talking

- Go Juxtapose

Let me know if anything of what I’ve said sounds like you might actually be interested in reading. However: I can only afford to buy a limited number of readers.

###

Image credit: Daniele Buetti via 2headedsnake

Ben Kyle: Hey—What if We Did a Living Room Tour?

The Dog Days of DIY

There is no one on the other end of this telephone connection who can help set up my new smartphone. With my last several technology purchases I’ve found myself alone in the final fine-tuning that actually makes the device work. Oh—there is certainly tech support. But my questions seem to send the customer representative to their supervisor (>30 minutes on hold) for answers. Not because I’m so smart, only because I am the chief of my cobbled-together IT system and I seem to always demand awkward things of said system. This is my penance for pushing for non-standard capabilities.

There is no one on the other end of this telephone connection who can help set up my new smartphone. With my last several technology purchases I’ve found myself alone in the final fine-tuning that actually makes the device work. Oh—there is certainly tech support. But my questions seem to send the customer representative to their supervisor (>30 minutes on hold) for answers. Not because I’m so smart, only because I am the chief of my cobbled-together IT system and I seem to always demand awkward things of said system. This is my penance for pushing for non-standard capabilities.

But maybe do it yourself is not such a bad set of expectations.

And maybe do it yourself is the future of, well, everything.

A local artist I find myself listening to again and again—Ben Kyle of Romantica—seems to be doing this very thing. He’s taking his music into the homes of friends and strangers. Right into their living rooms. Pot-luck and BYOB. Sign up here and you’ll see Ben singing from the ottoman. Can this be literally true—have I got this right?

If so, I’m watching for other artists to do the same. Why not run a DIY art gallery (oh, wait, that’s been done for years). Why not bribe neighbors with brats and beer to come to my book reading? Why not summon an interpretive dance-off on my front lawn?

As a nation we’ve always been enamored by fame. Anyone’s definition of “making it” inevitably carries some component of fame. You’re a success when everyone knows your name. If everyone knows your name you are a success. How else to account for the seeming success of the Kardashians who are famous for being famous?

But this DIY future doesn’t look like mass audiences following influential taste-makers. At least not at first. Ben Kyle is on to something that real influencers have known for years, that building an audience is a person-by-person activity. This is the word-of-mouth model: generally slow but immensely effective.

And maybe anything worth doing is worth doing one-on-one, despite what our national psyche longs for. I’m with Mother Teresa on this one:

Do not wait for leaders; do it alone, person to person.

###

Image credit: Francesco Romoli via 2headedsnake

There’s Something About Out

Out Always Informs In

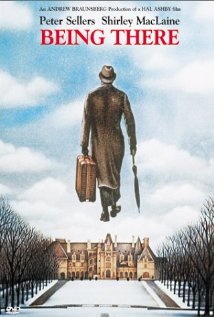

Chance tended the garden of a wealthy old man in Washington D.C. and had done so all his life. When his wealthy employer died, Chance was turned out into the [mean] streets. All Chance knew was the calm of the mansion and all he knew about the world outside was what he saw on TV. And so began Being There, one of the last films made with Peter Sellers way back in 1979. You might call Being There a dark comedy and it was certainly not for every audience.

Chance tended the garden of a wealthy old man in Washington D.C. and had done so all his life. When his wealthy employer died, Chance was turned out into the [mean] streets. All Chance knew was the calm of the mansion and all he knew about the world outside was what he saw on TV. And so began Being There, one of the last films made with Peter Sellers way back in 1979. You might call Being There a dark comedy and it was certainly not for every audience.

The scene playing in my mind today is Chance stepping away from the calm of the mansion and out into the urban chaos, complete with garbage everywhere, burning cars and a host of other stereotypes. The movie is all about how he is received by those he encountered.

In a sense Chance came alive as he left the stately known environment. This fits with what I’m coming to understand about taking what I know out to others who don’t know it. Whether it is what I know about medical devices or carbon fiber or my theological and faith commitments or what I know about bicycle routes in Minneapolis/St. Paul. Whatever I know, whatever is familiar to me changes in perspective the moment I try to explain it to someone else. Maybe I succeed in convincing my biking friend to take the river route I like. Maybe I fail to get my reading friend to take interest in the book I liked. Maybe I’m helping my client explain a unique heart monitoring system to an audience of physicians. Whatever it is—and in every case—how I explain myself to those outside changes the way I look at the priority. I immediately learn something new as I try to explain. And the organization changes as the communication happens: as we form words together to explain out product to an outsider, we on the inside understand something different as well.

And it’s not just what I know, it’s what is important to me. And maybe this is the heart of the learning: can this thing be important for someone else? And if so why or why not? And all this communication changes us.

My only point is that we need to actively take our priorities and knowledge with us out into the relationships we feed throughout every day. That’s how we grow.

###

Why I Like the Dumb Sketch Approach to Life

The Lure of Rough Drafts, Quick Observations and Badly Drawn Lines

I made this dumb sketch when visiting our son working in Madison, Wisconsin. Madison holds lots of memories for Mrs. Kirkistan and I: we went to school and met at the UW, we met amazing people who remain friends today decades later and made big directional choices. It was a place for fiddling with and setting trajectory—it still is that today.

Like most summer weekends there was a concert on the Memorial Union Terrace. This jazz festival (see dumb sketch) was running all weekend. These days it seems all of Madison turns out at the Terrace.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

One of the functions I relish as a copywriter is this responsibility to provide a rough draft. The rough draft is this work of writing out the position or power of my client’s product or service so others can respond. Or sometimes I’m summarizing and sharpening the science behind a product so we can see more clearly why it is important. Rough drafts are both right and wrong at the same time. The power of the rough draft is to set a thought out in the open where others can reach and tag it. After all, you can’t change something that doesn’t exist. The point is collaboration: how is this right? What do we know that can make this more right?

Saying aloud what we know and what we believe is the verbal equivalent of a rough draft. And saying aloud what we know is more than helpful. It is part of the human condition and not to be missed. Our conversations reveal who we are and what we know even as they and invite participation. Getting it wrong sometimes is part of the deal.

That seems like a good approach to life.

###

Image credit: Kirkistan