Archive for the ‘curiosities’ Category

Is Death a Natural Part of Life? I say “Yes.”

Bodies are finite. Souls—not so much.

Our pastor is fond of saying “Death is not a natural part of living.” His statement is especially apropos when confronted with the death that seems so senseless and tragic: the death of a newborn child, or the death of some fresh young person moving through life powerfully with plans, ideas, momentum and devotion. Death seems so wrong. So unnatural.

I deeply lament with the parents of the child whose soul resides with God but whose body is has gone back to the earth. I pretend no knowledge of the knife blade of emotion behind such loss. I know God promises His presence—that He is as troubled and full of lament and weeping (remembering that Jesus wept at Lazarus’ death—John 11.35) as the parents. And that’s as far as I know.

My wife and I have a running controversy about whether sin brought physical death or some other kind of death. In other words, if Adam and Even didn’t disobey God in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 3), would they have continued living—perhaps forever? My position is that the human body has always been finite—even in that perfect place before sin entered the world. I maintain that the very limits introduced to us by our bodies speak incessantly to the deep dependence we have on God at every turn in life.

It’s not as easy a question as it at first seems. If you think back to the Genesis texts, there’s no question that sin introduced a world of pain: literal and figurative. Just read Genesis 3 for the list of pains to expect. But at the end of Genesis 3, it is clear that men and women could no longer live in the garden because they might eat of the tree of life and so live forever (Genesis 3.22). So, banishment.

Calvinists and other reformed folk tend to think of the pre-sin version of humanity as also immortal—at least that’s how Millard Erickson sums it up in his “Christian Theology.” And if you are a fan of the Apostle Paul’s writings (as many reformers were and are), you’ll likely agree. Paul seems to often equate sin and death, for instance, in his letter to the Romans: “Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned….” (Romans 5.12) Other verses share and expand that sentiment. But did Paul mean physical death? Did God mean physical death when we warned against the eating of the fruit of that particular tree (Genesis 3.3)? Because physical death—immediate physical death—was not the result. Yes, Adam and Eve did die physically eventually. But was there a kind of death that occurred at the moment of sin?

Why Does this Matter?

This matters because of the day-to-day conversations we were designed for. The human frame was, is and has always been a fragile and needy instrument. Powerful in many respects (as any history text will attest), but profoundly weak when it comes to aging and decay. Botox and plastic surgery are of limited use. Our very weakness, on display day by day, is the thing that reminds us of God’s awesome power and keeps us coming back to talk. Moment by moment.

So—to say that death is not a natural part of life takes something away from the power and grandeur of God. It takes something away from his glory and seems to prop up the notion that we could have been able to keep on without God.

The point is our limitations constantly call us back to the original and originating conversation with our Creator. Those limitations and finitudes are built into our fabric. Mostly we seek escape from our limitations: thus Powerball, casinos and our ongoing proneness to financial scams. But what if we focused more on the conversation with the limitless One and less on fixing our limits?

What do you think?

###

Sometimes a Conversation is an Image

We Act Out What We Cannot Say

There are moments when we are open to listening. These moments may indicate we are open to change as well. People have been telling me their stories about conversations that changed their lives. Sometimes an inconsequential conversation at an inconsequential time can make all the difference in the world.

Louise Bell tells of a moment, not exactly a conversation but an image, that changed her life. Years ago her African-American grandparents had been murdered in the most gruesome way over an act of mercy on their part. Justice had not been accomplished in their murder and the wound was deep. It was when Louise mother died, after moving back to the south with an interest in reconciliation, that this moment occurred.

Listen to the December 30 edition of The Story over at American Public Media. It’s in the second half of the show.

###

Listen Up: #2 in the Dummy’s Guide to Conversation

The problem with listening is the other people who keep talking

You’ve opened your pie hole and made like a human: shaping experience into words that can be understood by the humans around you (though it’s still a bit fuzzy how anyone understands anything). You anticipate being stopped dead in your tracks with realization or wonder, right in the middle of a conversation.

You’ve opened your pie hole and made like a human: shaping experience into words that can be understood by the humans around you (though it’s still a bit fuzzy how anyone understands anything). You anticipate being stopped dead in your tracks with realization or wonder, right in the middle of a conversation.

But there’s a step to bridge the two: you’ve got to listen.

The traditional problem with listening is other people: they keep talking. When they are talking, you are not at the center and they keep uttering words that don’t refer to you. For instance: they rarely mention your name, which you keenly listen for. They keep talking about their own experience. Why, oh why, don’t they stop talking and ask me about me?

Let me introduce you to three friends who knew something about listening: Mortimer Adler, Alain de Botton and Jesus the Christ. I met Mortimer Adler when I read his book, “How to Read a Book.” Why read a book on how to read a book? Because of the author’s crazy fascination with understanding. He didn’t just read, he annotated, he outlined and he synthesized. He labored over passages in long conversations with the authors. Plus, he made it sound like fun (which it is!). Of course, there is not enough time to do that with every book, so Adler picked what he called the “Great Books.” His Great Books program has gone in and out of style over years, depending on your politics and your conclusions about who qualifies as worth reading.

Alain de Botton writes readable books that satisfy his curiosity and pull his readers into the vortex of questions he counts as friends. If you’ve ever wondered how electricity gets to your house or what is the process behind producing biscuits (that is, cookies) or why Proust is worth reading or why Nietzsche was not a happy-go-lucky guy, de Botton is the author you want.

Jesus the Christ knew something about listening, despite being both God and man. His human condition opened a limiting opportunity which in turn caused him to steal away for hours to converse with the God of the universe. I go into depth on this in Listentalk. But the point is that prayer, which is ultimately more about listening than talking, was a preoccupation of the man who was God.

Listening opens us to hearing—which sounds like “duh” except for when you examine your own listening practices and realize how often you are thinking of something else entirely when your spouse/child/boss/friend/neighbor appears to be talking. But to really hear, to be crazy to understand, to be curious and to be committed to connection opens us to the place where we can be stopped dead in our tracks.

###

Stop Dead in Your Tracks: #3 in Dummy’s Guide to Conversation

Could Paying Attention be the New Black?

This has happened to you: Going along. Minding your business. Dashing off small replies to the usual small talk. Maybe you hint at the plus-sized existential questions colliding and storming through your subconscious; the doubts and uncertainties that threaten to spill through your cranium as a conscious thought you even might utter. Maybe you stay silent.

This has happened to you: Going along. Minding your business. Dashing off small replies to the usual small talk. Maybe you hint at the plus-sized existential questions colliding and storming through your subconscious; the doubts and uncertainties that threaten to spill through your cranium as a conscious thought you even might utter. Maybe you stay silent.

But the internal roiling doesn’t let up.

“What does it all mean,” you mutter under your breath on the elevator to the 23rd floor, remembering your wife’s comment about needing more attention and your boss using pretty much the same words and your doctor stating you need to focus on exercise otherwise diabetes is around the corner. That’s when the person next to you looks up from her phone and says,

“I don’t know, but the CDC says attention deficit disorder is on the rise.”

She smiles half a smile and goes back to her screen.

It hits you: Maybe there is a national attention deficit disorder and your life reflects it. Maybe our screens and multitasking so distract us that full-on attention is rare and becoming rarer. Since we carry the multi-tasking addiction with us into every conversation (like a drunk secretly playing out the context of the next drink), we simply have no bandwidth to attend the need, the threat, or the story (it is National Day of Listening, after all) playing out before us. And suddenly you long for an hour of blissful focus.

Black Friday may be a worthy day to consider that paying attention is the new black: the fashion statement that can only be given, not bought. And paying attention to what we say to each other—really listening—may be a gift that looks more like an investment in the future of a relationship.

If The Word Fits

If the first step in the Dummy’s Guide to Conversation is to open your pie-hole, proving you are both human and alive, then the second step is to listen. And the third step is to be stopped—or at least to be prepared to be stopped. So much of life seems set to automatic pilot. The same bowl of Raisin Bran every morning. The same drive to work. The same greeting to the guard, same conversations with the same coworkers. Same words sent. Same words received.

When we have the Aha moment on the elevator to the 23rd floor next to the woman immersed in her screen, we should take note. Write down the insight. Listen to it. But don’t stop there; consider making a habit of watching for the moments of supreme attention that stop you dead in your tracks with wonder. These are the very pivot points we shoot past without even taking in the scene. And that’s too bad, because we miss an opportunity to learn something about ourselves, our culture and our future.

###

“Turn Off Your Mind” is One Approach to Faith. It’s Not a Good Approach for the Person of Faith.

In which I post about God, thinking and hypocrisy (my own). Skip if offensive.

Let me pull back the curtain on faith as I’ve seen it practiced—if only just for my own peace of mind.

[Full Disclosure #1: I am not writing from a generalized “faith” perspective. Instead, I write from the specificity of a follower of Jesus the Christ, who I believe was/is the Trinitarian God and who lived, died and lived. Further, I believe persons must act on their belief, because that’s what Jesus the Christ said. He made the point, which I believe, that the only way to God was through Him (including trying to be good enough which—logically—could not possibly work). Comment/email me to talk more about this.]

“Turn off my mind” has popped up countless times since I was a lad. The phrase has often been offered to me as the reason why people would choose not to believe in God or Jesus the Christ. It went something like, “Look, I’d have to turn off my mind to be a follower of Jesus.” Sometimes the phrase went: “I’d have to turn off my mind to go to church.” The first phrase I disagree with. The second phrase may actually be true.

It’s an Honest Assessment

Maybe you’ve heard or said this phrase or one like it. It’s an honest statement that reflects many things. For instance: a reasonable or scientific person may feel they would have to turn off their mind to embrace faith in Jesus the Christ. Perhaps they think of faith in Jesus the Christ as a kind of voodoo/animism/magic because of the contra-logical behaviors and antics they’ve seen practiced in the name of faith. Maybe the religion they’ve witnessed seems not all that different from the ancients sifting through the bowels of chickens to determine the way forward. I respect people who grapple thusly. Faith in Jesus the Christ is simple—and profoundly not simple—especially with your mind engaged. Wrapping your mind around the actions of an infinite God is way more than just difficult. I would argue faith is a gift, which (happily) is the Apostle Paul’s argument too.

It’s Not (Necessarily) the Leap

It used to be that when my friend said “I don’t want turn off my mind,” I would always hear “I don’t want to make the leap of faith required to believe in this Jesus guy. Who knows, maybe it’s all a fiction. I won’t entrust myself to fiction.”

But my perception has changed over the years as my own doubts and questions about how people have practiced their faith. Now I hear “turn off my mind” and understand there are all sorts of leaps in our lives, and I wonder which leap is calling to shut down the mind.

We make leaps daily, from trust that the bus we’re riding on won’t be blown heavenward by a terrorist with a bomb, to trust that social security will be there when we retire, to faith that the authorities are telling the truth when they say the groundwater is safe despite the chemicals 3M poured in the soil years ago. All of us act on leaps constantly. We act on these leaps because every time we take the bus—so far—we’ve arrived safely at our destination. We act on the leap because we don’t have a choice about social security and we’re putting a little bit aside anyway (besides, no one really retires anymore). We act on faith by drinking tap water, but we’re also reading the reports and we may yet resort to bottled water (though no regulations govern the purity of that water). We make leaps of faith and generally keep observing and considering what’s going on with each leap.

Now I think the “turn off my mind” phrase as applying to my friend’s observations of lives governed by faith. Maybe he sees too many of us exhibiting a herd mentality with some gifted leader we’ve hoisted into a popish position (sometimes against the leader’s will) from which they inevitably fall (no one is perfect, after all) (except that one Guy). My friend feels he must turn off his mind because of the echo chamber talking points that roll off our tongues in response life’s deepest questions. I’ll confess to spending much of my life in mindless following as well. Just doing what I hear the preacher or leaders say. Thinking it’s true (often it was, sometimes it wasn’t). Following the paths everyone else followed—we’re all going the right way. Right?

The fact is it’s just much, much easier to walk the same direction as everyone else. Find a group that’s going in a good direction and jump in. And just stick with it. The problem is that groups need help in continuing to find the way and the leaders don’t always know the right answers. And sometimes leaders may even respond to other interests that become incompatible with the original direction.

Faith Infrastructures are Culturally-Based

It turns out that much of the infrastructure surrounding faith is culturally-based. It’s always been that way. How we are together is not truth in the sense that God said it. Much is invention. People who say “I don’t want to turn off my mind” are not stupid—they see artifice (perhaps even built on something that might be believable) and turn away whether or not they can say why.

[Full Disclosure #2: I take the Bible as the Word of God, which means I read and understand it as a document where the usual rules of interpretation apply. But the words I’m reading carry much greater authority than, say, the New York Times. Further: I believe God helps readers understand His words (which carry mystery and are not always black and white). I see the Bible as a living document that pulls me into constant conversation with the God of the Universe. That’s my leap.]

I’m saying this just to point out that there are many leaps we each take every day. I want to invite you toward the great mystery of knowing God, in any way I can. I also want to avoid turning people away because of my pat answers.

###

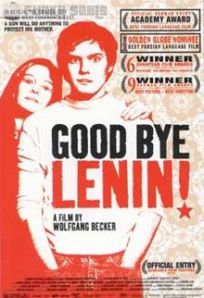

Good Bye Lenin. Hello Target.

How far do you take a lie to protect someone?

Alex Kerner (played by Daniel Brühl), his sister and their mother lived in East Germany. But Kerner’s mother, a faithful socialist, had a heart attack and fell into a coma the night the Berlin wall came down. When she awoke eight months later, Kerner wanted to keep her from a second heart attack, which her doctor said could kill her. So he followed her doctor’s advice and recreated his own version of East Germany to protect his mother.

This dark comedy is funny because of Kerner ‘s success in creating the illusion of an ever-excelling East Germany. It gets funnier when Kerner invites others into the sham. But it’s funniest and touching at the end. I won’t say exactly why, but it involves an East Germany accepting refugees from the West escaping the ravages of consumption.

Along the way lies get told, naturally the lies must be multiplied and amplified, televised and dramatized. It is clear the untruths cannot continue, and truths begin washing through the story. Conversations that sidestepped truth and walked circles around reality eventually succumb to both love and trust.

I could not help but ask what illusions I create for myself and invite others to be part of. We all need the kind of conversations where truth is spoken, no matter how it seems to change reality.

###

I Quit You, Right-Hand Page Beginnings

I might stop printing. But you’ll have to pry transitions from my cold, dead hands.

I’ve been doing things differently without realizing it. For over twenty years I’ve inserted a blank page at the end of sections and chapters so my next section or chapter can begin on a right-hand page. I admit to finding a certain elegance in beginning a new thought on the page lying flat before me and close to my right hand. It just felt right.

No more.

Most of the documents I produce for clients will be used electronically. Few even consider printing them because, well, why would you? Since the screen is always there…and since paper just gets lost anyway…and since as soon as you print something, it changes and your print is outdated…so why print something again? Current audiences will not realize how a right-hand page lies flat on a surface while a left page bubbles up and distorts—an open invitation to move forward.

It’s not just blank pages. Transitions are transitioning away. Remember when transitions were the thing: when you wanted to gently lead your reader from one topic to the next, from one moving part of your argument to the next? Some writing textbooks still talk about making transitions in your writing. But are the days of transitions—just like the days of inserting blank pages—are swiftly passing. Since everything is modular we expect to jump from topic to topic rather than be wooed along.

Nicholas Carr in The Shallows talks about the atomization of information. How books and chapters and articles are already being dismantled so pieces are available here, there and everywhere. People writing books with the help of social media use the situation when they post as they go, so potential reviewers have the opportunity to interact with the writing long before it is even put in the longer (and more expensive book form). One of the dangers is that writers will write for short attentions spans—wait aren’t those people called bloggers and copywriters?

In truth, writers have always written for short attention spans. Back when reading books was the thing smart and interesting people did, writers talked about the reader’s constant pressure to walk away from the text. That was a key motivation for the writer to make the text more interesting. In my writing classes we often lament the lack of readers (in general) and the reader’s constant temptation to click away from the text. Clicking is so much easier than walking.

Blank page insertions may go away, but I doubt transitions will. That’s because communicators still have an innate need to keep an audience interested. Blank pages may be an artifact from the printing days. But transitions are a piece of our humanness that is alive and well and will stick around until our final…transition.

###