Archive for the ‘Teaching writing’ Category

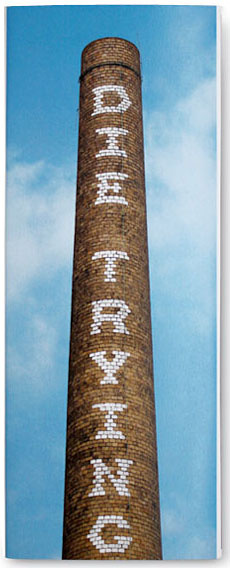

Copywriting Tip #3: Words + Images (Think Visually)

How To Think Visually?

Thinking visually and combining words and images is something of a kaleidoscope experience. Especially for the English major. These folks love words and regularly ask them to leap and dance and bite and romance. English majors have been going steady with words for years. I’m asking these people to see others—but it’s not about two-timing your fascinating Helvetica friends. Just add an image to the mix and step back: did the image just comment on the words—or vice versa? Did the words explain the image? Or did the words supply a subtle subtext that subverted the image? Or vice-versa? Now we’re spinning the kaleidoscope and it is all sorts of (kinda nerdy) fun.

Hint: Don’t Start With The Google Machine.

The temptation is to type your first thought into the search bar and see what images pop. This lazy approach will be at least mildly amusing and completely distracting for the next 73 minutes. There is a more productive way to begin: pen and paper. Any number of artists and writers will tell you that working through potential ideas in the isolation of a blank page helps you focus. The drill is to do it again and again. Page after page. Hour after hour. Until you can’t stand it anymore. From all that terrible, worthless dreck that you would never show your mother let alone the cute human in your Classics class, pick the two or possibly three that don’t make you wretch. That are kinda ok. Google those.

The key is to get your brain working and keep it working long enough that your subconscious takes up the project, freeing you to walk around the lake or pull a prank on your roommate.

You will produce something in this manner.

Try it and tell me if it worked.

###

Image credit: Maximum stacks/Creative Review via thisisn’thappiness

Below: dreck. Maybe an ad came from it. Maybe not.

Copywriting Tip #1: Love the Study

In Freelance Copywriting (Eng3316) we’ve started producing work in earnest and every week (including tomorrow) another student piece moves into their portfolio. All the students have signed up for work they’ve never tried before—ad concepts, radio scripts instructional booklets, and many other forms. All according to where their writing passions are leading them.

In Freelance Copywriting (Eng3316) we’ve started producing work in earnest and every week (including tomorrow) another student piece moves into their portfolio. All the students have signed up for work they’ve never tried before—ad concepts, radio scripts instructional booklets, and many other forms. All according to where their writing passions are leading them.

One thing I love about copywriting is learning new stuff. Whether it’s asking a doctor questions during brain surgery or watching a silicon wafer get doped and fired or learning about the medicines Lewis and Clark used (forced marches and blood-letting seemed to resolve a lot of their ailments). There is no end to fascination with how the world works. Putting what I learned into words (and images) electrifies the whole task: spooling out my argument and helping show why anyone would care what the patient said while the doctor probed his frontal lobe, or why ramping quickly to 900 degrees centigrade matters when firing a wafer or why Dr. Rush’s bilious pills had such a strong…(ahem) purging effect—it’s a puzzle that rewards more as I attend to it. Words and ideas are the puzzle pieces. The goal is to engage very particular audiences (with much shorter sentences than I’ve used here). James W. Young would call this the gather and masticating stages of the process. How could you not love this work?

Part of the research is figuring out what makes a good print ad. Or what makes a radio spot compelling. In other words, what forms have people used to tell these stories in the past and how do we use these forms today? Or do we pick a new form (which typically means recycling another older form)? These are questions we answer again and again as we look at what’s being done today and revisit the best of the best.

But love of learning is the engine. And putting things into words is the transmission. These are the bare bones vehicle of a copywriter.

###

Image via Copyranter

Wait for It (And Resist Checking Your Phone)—Dummy’s Guide to Conversation #8

Anyone who writes for a living or who must regularly produce creative solutions knows the best ideas are typically not the first ideas.

I’m about to begin teaching a freelance copywriting class at Northwestern College and I’m guessing there will be some who will submit copy they’ve done at the last minute: something thrown together to meet the assignment requirements, but just barely.

I hope college students don’t remember college as the place where they learned to do the least at the last minute to see how much they can get away with. This is not a great attitude to take into the workplace. And it is a fatal if you work on your own, because it leeches craftsmanship (and joy) from the work itself. And craftsmanship—care for the work itself—is one of two key elements in meaningful work. The other element is learning how to serve someone else’s needs and finally get over yourself.

When I brainstorm for an ad or a bit of copy I fill up pages and pages with pure dreck. Worthless stuff that only serves to get my keyboard moving. And then, at some point, one bit of dreck solidifies into a line that is sort of ok. Or a direction that makes sense. But that only comes after the pages of dreck. Occasionally it comes first, but I need the pages of dreck to help me realize any possible or potential brilliance.

How does that work in conversations? Same way. The first stuff we way say is obvious and not that interesting. The first conversations of a cross-country car trip have a vanilla flavor. But by the time you’ve arrived at New York to catch a flight to Europe, you know the deep hurts and high joys of everyone in your car, and you’ve somehow settled on a series of jokes about fast food restaurants or particular car types that leave you all gasping for air because they are so funny. It takes time and sustained attention to get to that place where the good stuff comes out. It’s almost like you invent the context for familiarity as you go.

This is the way for lots of satisfying things. And it is the way for ordinary conversations. I’m learning to dwell in a conversation. To not rush it. To give myself and other space to breathe so that they (and I) feel free to let come what may. And that can be uncomfortable because silence is awkward for us. Soap opera stars lock their eyes in those silences. In a cross-country car ride you look out the window. In a conversation, you just…look…and wait. But the silence works to lube thoughts. Resist the urge to move to the next thing. Resist the urge to pull out your phone. Wait for it. Because eventually something will come along that changes everything.

###

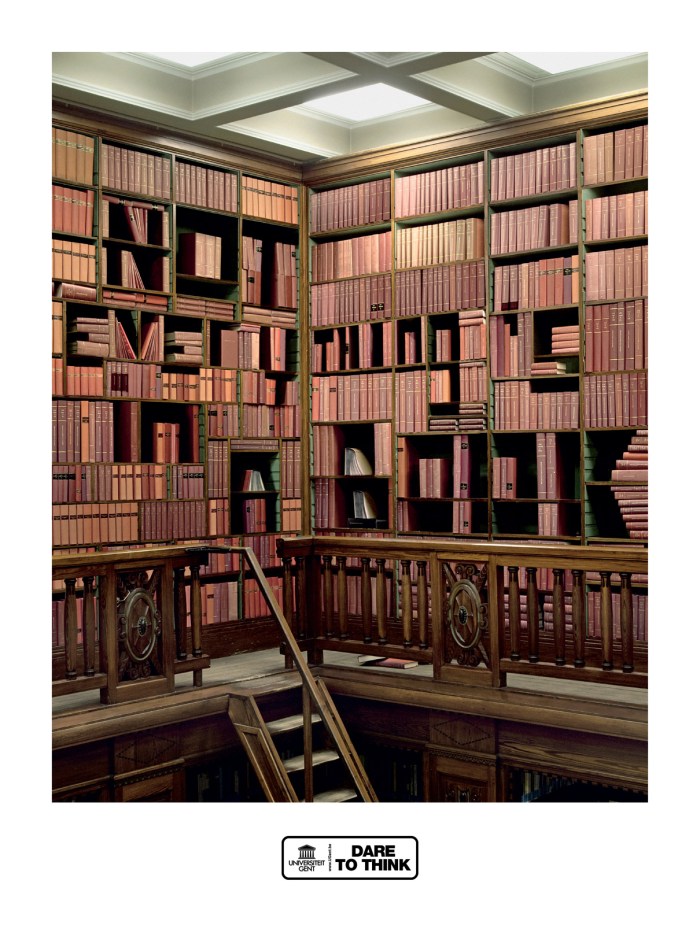

Image Credit: Langdon Graves via thisisn’thappiness

Risky and Risqué Reading for Christian Copywriting Students

On Tuesday I start teaching Freelance Copywriting (Eng3316) at Northwestern College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. These are junior and seniors largely from the English department, but also from Journalism, Communications and Business. They are generally excellent writers and engaged students—people eager to take their faith into the street. We’ll use a few thought-provoking texts that deal with the business side of copywriting, along with the what to expect as a copywriter and how to get better at producing salable ideas (Bowerman’s The Well-Fed Writer, Iezzi’s The Idea Writers, Young’s A Technique for Producing Ideas). But I’ve become convinced the real-time critiques of working copywriters around the web are just as helpful if not more useful than our texts. It’s just that the language and images used in the critiques often veer outside the lines of nice and polite, though I would argue the critiques follow the line of conversation Jesus the Christ encouraged with regular people like me.

So.

I’ve devised a warning:

Question: Is this overkill? My goal is to help prepare thoughtful writers who fold God’s message of reunion into their communication work and live it out in a world that operates on a very different basis. I think students will understand. I’m not sure the administration will.

What do you think?

###

Image Credit: Chris Buzelli via 2headedsnake

When Writing is More than Writing: The Idea Writers by Teressa lezzi (Review)

Your invitation to a new way to persuade

As editor for Advertising Age’s Creativity, Ms. Iezzi has a daily, close-up view of the trends in the creative world and the people behind those trends. The surprise in the book comes with the affection Ms. Iezzi has for the discipline of copywriting and the practical nature for those seeking to grow in the discipline. It is readable, informative and filled with stories about advertising heroes and insights into current campaigns. I plan on using it as text in my next class on freelance writing.

As editor for Advertising Age’s Creativity, Ms. Iezzi has a daily, close-up view of the trends in the creative world and the people behind those trends. The surprise in the book comes with the affection Ms. Iezzi has for the discipline of copywriting and the practical nature for those seeking to grow in the discipline. It is readable, informative and filled with stories about advertising heroes and insights into current campaigns. I plan on using it as text in my next class on freelance writing.

Ms. Iezzi begins by framing the story of copywriting with a look at the ground-breaking work of legends like Bernbach, Ogilvy, Reeves and others back in the 1960s. Their work was fresh in relation to what was going on around them. Indeed that decades-old work formed the basis of many of our current communication trends. Ms. Iezzi uses the legends to reinforce the importance of storytelling, which these guys got right. Storytelling is the concept that best binds together The Idea Writers, as Ms. Iezzi issues a kind of challenge to today’s batch of copywriters to push into the new ways of communicating.

Two powerful notions emerge from The Idea Writers:

- Copywriting today is much more than only writing. Maybe writing was always more pure than writing. Today’s copywriters will sketch designs, draft scripts, work out the voices of a cartoon and a blog persona. They will pitch ideas because they are closest to the energy behind the idea and because organizations run much flatter. This book helps break through the silos that are already on their way down.

- Today’s copywriters help guide brand development following new methods of persuasion. In this new age, people buying stuff have unprecedented control of brand. Today’s copywriter recognizes the stories that honor the people doing the purchasing while smartly positioning the brand as a kind of conversation partner.

Ms. Iezzi’s book is the first copywriting book I’ve read that does justice to the emerging notion of the switch from corporate monologue to personal dialogue. The only lame part of the book came when she trotted out her personal list of tiresome cliché ad ideas. Her list of six included things we all instantly know, but to say those ideas will never work again seems like a challenge. The list also invalidates the notion that we beg, borrow and steal good ideas constantly—it’s just that those ideas are more or less recognizable in a different arena.

###

Where Does Insight Come From?

How do I discombobulate without getting fired—or hired?

Over at the Philosopher’s Playground, Steven Gimbel wrote recently of his need to discombobulate his students (with their “naively smug beliefs which they’ve never thought very hard about.”) to help them begin the work of philosophy. I wonder if the act of getting discombobulated is the beginning point for producing any insight.

A few days back I had coffee with a friend who is a human resources executive and coach and thoughtful person. We were talking about what makes an organization dialogical, that is, willing to enter into conversation internally (versus the usual barking of orders from one management level to the next). Carol, as it turns out, had a keen interest in how dialogue works and was able to identify four stages in a verbal exchange required to produce insight:

- Awareness of a problem or issue

- Trigger: something in the exchange triggers a reflective moment. Insight often falls from the reflection

- Insight: the Aha moment, when suddenly I understand something previously opaque to me

- Action: Do something with an insight or it is gone. Write it down. Tell someone. Do anything.

Gimbel’s discombobulation seems to help with the awareness phase. We need to understand how what we thought certain or easy is neither certain nor easy. Sometimes I use a classroom exercise to help create the trigger/reflection step for my students. But just as often, in ordinary conversation, my discombobulation finds relief when my friend asks a question and I lapse into momentary reflection which often leads to an insight. Sometimes I feel like an “Aha” addict: there’s nothing like suddenly realizing a new truth—nothing like that “click” when a critical piece of how life works suddenly falls into place. That’s a big part of why I write.

Perhaps the key to those four stages is the action part. We need to do something with an insight. Right then at the very Aha moment. Otherwise it’s lost.

But corporate conversations routinely detour around discombobulation. It’s partly a time issue but mostly the politics of a department: a boss or manager or VP rarely seeks out discombobulation, especially from subordinates. The person in charge would much rather pay a high-priced ad agency or consulting group to come in and discombobulate them. I’ve been on both sides of a number of those meetings.

I’ve been trying to help my students become active discombobulaters in their workplaces: from wherever they land, my hope is they ask the impertinent questions that poke through the malarkey and point out deviation from mission.

###