Archive for the ‘What is work?’ Category

Can You Engineer a Conversation? (How to Talk #2)

Depends: Are you looking for control or insight?

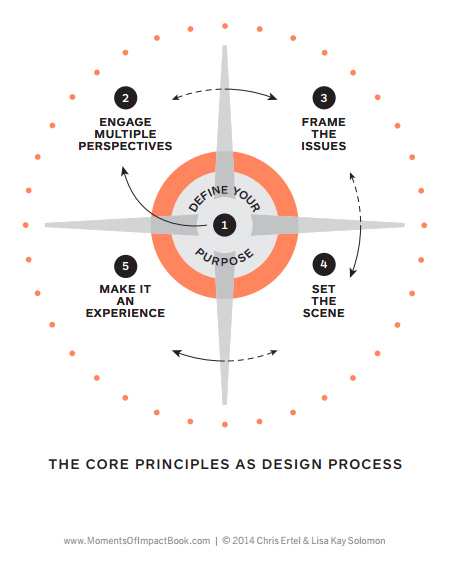

In Moments of Impact: How to design conversations that accelerate change (NY: Simon and Schuster, 2014), Chris Ertel and Lisa Kay Solomon argue that some of our most productive conversations come from deciding ahead what we want from the interchange. Their book presents a system of on-ramps that will be particularly useful for anyone charged with gathering a group with the intent of going further than the old, fallow brainstorming sessions allowed.

Conversation, as everyone knows, can be far from benign. For those looking to control a conversation, unless highly skilled, the better (and far less productive) option may be to continue with monologue.

Because a strategic conversation consists of live interactions between people with different perspectives and passions, you can never predict exactly where it will lead. (41)

That is the beauty of conversation: the whimsy factor can drop participants in places they never expected to arrive. That is also the danger—especially in corporate settings where a particular outcome has been strongly hinted at, if not guaranteed.

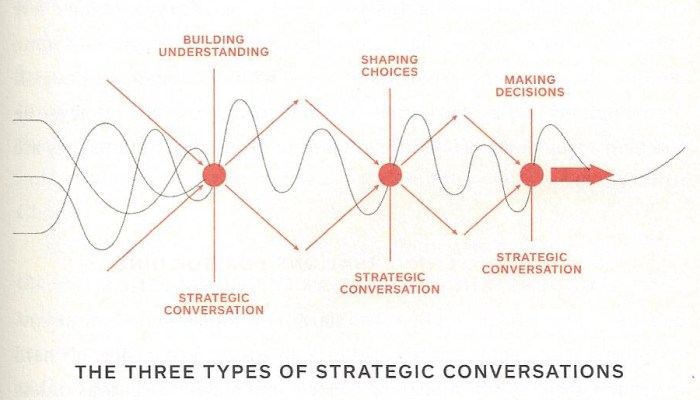

For those daring souls willing to let go, but who still retain a preferred outcome, Ertel and Solomon’s notion of a “strategic conversation” may just fit the bill. Start by sorting what you are trying to accomplish: build understanding, shape choices or make decisions. And then employ divergent and convergent thinking and other group exercises as necessary.

What I appreciate about Ertel and Solomon’s work is they have built a framework around the basic serendipity of conversation and brought it as a tool into even very hierarchical structures.

I am convinced we’ll find strategic conversations a formidable tool indeed, especially as we create brand new stuff out in the world.

###

Image credit: http://www.momentsofimpactbook.com

Wait—English Majors Win in the End?

Start Writing Your Own Future

- Announce your goal to lose weight and chances are better the pounds will flee.

- Sign up for NaNoWriMo and chances are better you will actually write that novel (no matter how badly it turns out).

What we tell each other has a way of happening. What we tell each other about our preferred futures has a way of guiding next steps.

- Write a letter to your collaborative, inventor friend about a business idea and find yourself planning concrete marketing and distribution steps at Spyhouse Coffee.

- Write a business plan for your startup and suddenly remember your friend who became a venture capitalist. And then remember the friend who bootstrapped her idea.

See the pattern? Each step forward started with communication. You may say,

“No. the idea came first.”

True—maybe.

But consider: the communicated idea created a spark. And—given the right collaborative conditions—the spark lit a fuse. And the fuse burned, gathering other ideas until the explosive, disruptive future no one had considered.

What if English majors learned entrepreneurship and began to see their talent for orderly, persuasive, deeply-rooted writing as a way to help themselves imagine new futures and chart forward-movement for others? What if they learned to solve real-world problems with story and emotion and analytics? Their solutions would drop-kick the spreadsheet & PowerPoint crowd. What if some English majors created Lake Wobegon while others created the next Google?

What if English majors learned business lessons alongside the standard fare of reading and writing? What if they were expected to serve up the occasional business plan or marketing strategy along with the usual essay, short story and poem?

If that happened, English majors would connect earlier in life that art and work and commerce and fiction and meaning-making all fit together in the same world. And they would begin to write their own future vocation.

By the way: 16 Wildly Successful People Who Majored in English

###

Caveat #1: I was never an English major.

Caveat #2: I teach English majors. They are smart, innovative people.

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Charles Chamblis: Photographer’s Notes

Story told by numbers

Charles Chamblis didn’t take too many days off from photography. With his camera he captured slices of life in the African-American community around Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota in the 1970s and 1980s.

Go see his collection of Minneapolis-Saint Paul photos at the Minnesota History Center.

More on numbers here.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Don’t Bother Me. I’m on Fire.

Too Busy: 4 Takes

- My contact is too busy to talk about collaboration: “Too many deliverables, scheduled too tightly.”

- Another colleague laments the lack of time to think ahead about the broader picture. She chides the constant race to get stuff done.

- A friend observing the inner-workings of a logistics department 2000 miles from where he was trained could identify key process components missing. The very components that created the immediate chaos the team waded through each day.

We earn our keep by being busy. None of us want the boss to wander by and say, “Fire up that keyboard/drill press/classroom/spreadsheet and get to work.”

Busy is always good.

There are no exceptions.

And yet:

- We lament “busy” but secretly get a buzz from opening the adrenalin spigot.

- Busy looks productive. But looks can deceive. We easily deceive ourselves with busyness.

- When taken out of action (for instance, when downsized/right-sized/laid-off/fired), we suddenly have time to ask:

- “Where am I?” and

- “What (the heck) am I doing?” and maybe

- “What was I thinking?”

- No one likes the off-balance, adrenalin-free stance of waiting, watching, knocking and waiting. Are we genetically predisposed to seek action? After all, aren’t verbs the action-heroes in our favorite writing?

It’s hard work to look at the bigger picture and make difficult choices about direction, use of resources, usefulness. And yet those are the very questions that help us move forward. As the wheel of seasons grind toward winter in Minnesota, we might take a page from the farmer’s playbook and let snowy fields lie.

Even on purpose: the fallow field may allow us productive time to consider what it means to be productive.

Versus just busy.

###

Dumb sketch credit: Kirk Livingston

Rob Moses & the People of Calgary

“Have you ever ridden a horse?”

If you’ve had the pleasure of going to Calgary you’ll know it is truly a western city. Situated not far from Banff and Jasper National Parks, it is also quite spectacular. And rich, fueled by oil and gas money flowing into the city.

Rob Moses is a photographer based in Calgary. I follow his blog because of the extraordinary portraits he takes of complete strangers. His method is to approach someone, have a conversation, and shoot the photo. The endearing thing about this process is the conversation he has. He records it verbatim —or so it seems. His written text includes nervous laughter, indecision, and ricocheting answers. His recorded conversations sound like real conversations to my ear.

Stopping complete strangers is not easy in the best of situations. Asking to take their picture sounds like a scam, but Mr. Moses pulls it off with what seems to be a fair bit of joy. And he always asks if his subject has ridden a horse—critical information for Calgarians, evidently.

The optimism of sharing his talent with photography is not lost on me here. It’s kind of an amazing way to self-promote and, well, bless people. And for those lucky enough to find their way into his lens, they come away with a phenomenal view of themselves. Scroll through his blog and be amazed at the composition, lighting and the ease written on the faces of his subjects. If you’ve ever asked to take someone’s photo, you know it typically ends badly. Unless you are Rob Moses.

May there be more of his talented tribe.

###

Image Credit: Rob Moses

Could Your Organization Grow Your Spirit?

LEED-like certification for human-spirit-sustainable workplaces

LEED certification is a rating system that recognizes a building’s sustainability. LEED or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, rates a new building project using five different categories:

- Site location

- Water conservation

- Energy efficiency

- Materials

- Indoor air quality

Businesses and organizations with the highest ratings display them as a sort of badge of honor for the public to see.

What if there were some system to measure and rate the culture within a company or organization? Since we worry about bullying at school and we’re starting to recognize bullies in the office and toxic corporate cultures, does it make sense to start thinking about organizations that sustain people rather than beat them?

For instance, what if any organization was judged by these four categories:

- Bias toward collaboration

- Employee engagement indicators

- Mix of top-down messaging with true conversation

- Ratio of CEO-pay to rank-and-file pay

Seem ridiculous?

It would be difficult to measure many of these, especially since most of the categories seem so subjective. And yet, would it be impossible to measure? Would it be worthwhile to measure? Are we already moving in that direction?

In Minneapolis/St. Paul—like any set of cities—insider talk has long identified those cut-throat corporate and institutional cultures that routinely toss human capital to the side. Insider talk also identifies those bosses, managers and C-suite people without empathy and/or ethical moorings. New employees are generally forewarned when they sign up.

Of course, business is still about earning a living for the people involved even as the organization serves some human need. So don’t think I’m championing some communistic collective. Profits will and must be made to help society move forward.

But as we move toward fuller employment, workers will become more choosy about where they spend their days. And those cultures that have a less sustainable ethos will not be the winners.

I’m not convinced I’ve identified the right categories to measure. What categories would you include?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

No, Really: What does a Philosopher do?

When Adjuncts Escape

Helen De Cruz has done a fascinating and very readable series of blog posts (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) tracking the migration of philosophical thinking from academia into the rest of life. As low-paid, temporary workers (that is, “contingent faculty” or “adjuncts”) take over more and more university teaching duties (50% of all faculty hold part-time appointments); smart, degreed people are also starting to find their way out of this system that rewards increasingly narrowed focus with low pay and a kick in the butt at the end of the semester.

Ms. De Cruz has a number of excellent interactions with her sample of former academics (at least one of whom left a tenured position!). I love that Ms. De Cruz named transferable skills. What would a philosophy Ph.D. bring to a start-up? Or a tech position? The answers she arrives at may surprise you.

I’ve always felt we carry our interests and passions and skills with us, from this class to that job to this project to that collaboration. And thus we form a life of work. Possibly we produce a body of work. We once called this a “career,” but that word has overtones of climbing some institutional ladder. I think we’re starting to see more willingness to make your own way—much like Seth Godin described his 30 years of projects.

The notion of “career” is very much in flux.

And that is a good thing.

Of particular interest to me was the discussion Ms. De Cruz had with Eric Kaplan. Mr. Kaplan found his way out of studying phenomenology (and philosophy of language with advisor John Searle!) at Columbia and UC Berkeley to writing television comedy (Letterman, Flight of the Conchords, and Big Bang Theory, among others). If you’ve watched any of these, it’s likely you’ve witnessed some of the things a philosophical bent does out loud: ask obvious questions and produce not-so-obvious answers. And that’s when the funny starts. It’s this hidden machinery that will drive the really interesting stuff in a number of industries.

Our colleges and universities are beginning to do an excellent job dispersing talent. That thoughtful diaspora will only grow as time pitches forward.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Working Together: A Final Frontier

Talk Inc. Buries the BS Meter

Collaboration is hard for a lot of reasons. One reason is the power distance between people in a company. How can I say what I really think when I know my boss disagrees? Can I have a real conversation with an automaton who spouts corporate messaging and controls my salary?

Talk, Inc.: How Trusted Leaders Use Conversation to Power their Organizations by Boris Groysberg and Michael Slind starts with good intentions: to lay out this new challenge of interacting with employees as if they had something worthwhile to say.

But I should back up: old styles of management were about command and control: I’m boss so I’ll tell you what to do. And you’ll do it. New ways of thinking about the work of leadership and managing tout a more generous and collaborative approach to personal relationships. But these collaborative ways still have a hard time sifting down through the ranks of gatekeeping managers who intuitively see their mission as that of controlling others.

Talk, Inc. has a terrific vision, but the first section (three chapters on intimacy) is off-putting in that it quotes CEOs and VPs and various bosses at length, each talking about all they are doing to encourage collaboration.  But Groysberg and Slind may have done better to start at the other end: giving voice to employees who have been given a voice. As it stands, the first three chapters are a difficult slog because anyone who has spent time in a corporation will recognize the smarmy PR tone of the program-of-the-quarter. My corporate BS meter kept pinging into the red.

But Groysberg and Slind may have done better to start at the other end: giving voice to employees who have been given a voice. As it stands, the first three chapters are a difficult slog because anyone who has spent time in a corporation will recognize the smarmy PR tone of the program-of-the-quarter. My corporate BS meter kept pinging into the red.

The book gets better, but all the way through I struggled with the “trusted leaders” part of the subtitle. For a book that intends to talk about the power of conversation, there is still an awful lot of command and control monologue. Whether it was the suits from Cisco or Hindustan Oil talking, it was hard to take their comments seriously.

Talk, Inc. is, however, smartly organized into four sections (Intimacy, Interactivity, Inclusion and Intentionality). Each section has a chapter that plays out the vision, followed by a chapter that shows a company trying to carry out that particular part of the vision, followed by a “Talking Points” summary that helps the reader play it forward. The Inclusion and Intentionality sections offer more thoughtful reasoning and vision-casting for changing corporate culture so real conversation can happen. Groysberg and Slind offer solid examples of organizations that work hard at listening. But this is a story that really needs to be told from the “newly-voiced” perspective.

Talk, Inc. is, however, smartly organized into four sections (Intimacy, Interactivity, Inclusion and Intentionality). Each section has a chapter that plays out the vision, followed by a chapter that shows a company trying to carry out that particular part of the vision, followed by a “Talking Points” summary that helps the reader play it forward. The Inclusion and Intentionality sections offer more thoughtful reasoning and vision-casting for changing corporate culture so real conversation can happen. Groysberg and Slind offer solid examples of organizations that work hard at listening. But this is a story that really needs to be told from the “newly-voiced” perspective.

###

Image credit: Bill Domonkos via 2headedsnake

Click Farms Vs. Philip Glass

The Glass problem: Prolific production of something no one wants.

I’ve heard rumblings of sweatshops where thumbs and fingers are put to use liking various social media status updates. An AP story running in the Startribune a couple days ago identified even our own State department as buying clicks, possibly from a click farm in Dhaka, Bangladesh. If not exactly illegal, the practice certainly carries the sense of fraud in the false “Like” economy Facebook introduced us to and to which all social media fall prey.

I’ve heard rumblings of sweatshops where thumbs and fingers are put to use liking various social media status updates. An AP story running in the Startribune a couple days ago identified even our own State department as buying clicks, possibly from a click farm in Dhaka, Bangladesh. If not exactly illegal, the practice certainly carries the sense of fraud in the false “Like” economy Facebook introduced us to and to which all social media fall prey.

The desire to be liked is so compelling. I’m hoping you’ll like this story (as if you needed to read such a disclosure). But I’m also trying to wean my myself off this desire for constant attention and this eagerness to let a click tell me how successful I am in life. There’s good reason to investigate the internal compass of gifting and bent and pairing those with the hope of connecting solidly with a few rather than seeking the transient adoration that “like” seems to represent.

Then again, the money is in the Likes.

A more balanced and possibly more productive approach to doing our best work is to dive ever-deeper into the well of “What am I here for?” When we ask that question and look to see what fascinates us and what (some, few) others react to or what seems to help those few, then we are on to something. That is a very different process than scanning keywords and offering click bait.

Consider Philip Glass. Maybe you like his music. Maybe you despise his “repetitive structures.” I find his music soothing and at times invigorating and always terrific for writing. But when he started playing and composing, it sounded very different thing from everyone else. He had very few “likes.” In fact many just said to him,

But he persisted and found something new.

That’s what I’m expecting from many: to find passion and service flowing together, even if others don’t understand it. It takes courage to keep walking forward in this way. But that’s the kind of courage we need.

###

Image credit: un-gif-dans-ta-gueule via 2headedsnake