Dialogue 2.0: Can a Marketer Game a Conversation?

Yes. But maybe no?

Lots of us try to figure how to turn a conversation to our advantage.

Marketers increasingly slip us information just when we want it, like Google giving directions to the donut place on the way to my next meeting.

Bad Google.

Carl Griffith, writing over at ClickZ, wants marketing websites to recognize and reengage with returning customers via their behind the scenes content management system. He wants websites to engage in dialogue like people do: no need for reintroductions. We know you—you know us—where did we leave off last time? Cookies help this happen, of course. Amazon is an example of picking up where you left off and adding suggestions for more purchasing joy. That is likely where all web properties are headed.

Mr. Griffith goes further: what if we programmed into our content management systems a way to pick up on non-verbals? He means those signals that pass between animate conversation partners (I wrote human first and then remembered how much non-verbal information dogs pick up): the open or closed hands, the orientation of shoulders or head toward or away from the speaker, the eye contact (or lack thereof)—all these bring depth and context to our conversations. That depth and context adds to the words exchanged or belies the words exchanged. Listen to Mr. Griffith:

You will be familiar with the throw-away lines in everyday conversations around the importance of non-verbal communication and what we have now in the world of digital are ways of understanding the more silent and less obvious conversations and dialogue we now have with our consumers driven by context and the insights we should derive from the sum of interaction and engagement.

As a consumer—or for anyone increasingly wary of how our own national security apparatus listens in at will—it’s easy to read sinister overtones into these marketing improvements. Marketers will want to be wary of any resemblance to the NSA, although all the players are starting to look like classmates from the same surveillance school.

But in a human conversation, we start to get the sense of when our partner is yanking our chain—or outright manipulating facts and/or lying. And we back away. Quickly. Perhaps the computer programs that touch our web conversations will go the way of 30 second TV spots—a chance for us to cognitively check-out because we know we’re being sold something.

Mr. Griffith’ vision of dialogue 2.0 is starting to sound like a return to monologue, only in shorter bits and micro-fitted and shoehorned into seemingly ordinary conversations.

Caveat emptor.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston (Weekly Photo Challenge: Street Life)

“Just Exactly What Are You Up To?”

Then ask: “What is your point?”

We ask this of each other constantly: “What’s your point?”

We also ask it of poems and movies and op-ed pieces and windy monologues and sermons and sacred texts and profane screeching. Is this desire to quickly get to the nub a peculiarly American trait?

Maybe.

Maybe.

Or maybe it’s just a sign of these fast-paced, self-important times. Unfortunately, the question allows little room for dilly-dallying with ambiguity or gray.

Because we got stuff to do.

We want the point. And we want it now. So we can reject it. Or, possibly we’ll agree (but with provisos. Naturally).

Authors and friends who take time to really get to know a subject or to get to know another person’s thought are great counterweights to this tendency. Mortimer Adler’s How to Read a Book comes to mind, with his intense working-over of a text so as to master it. This is the opposite of reducing this to that. And I’m lucky enough to have people in my life who listen carefully without reducing. I’m trying to learn from them to do the same

I’ve just begun a book by Joseph Harris, Rewriting: how to do things with texts (Utah State University Press, 2006). Mr. Harris’ book has lots of wise and useful things to say about how to handle other people’s thoughts in ways that allows you to hear them, while allowing room for moving the topic forward. He advocates a generous approach with a text: trying to understand. The generous approach to another person’s thought reminds me of Wayne Booth’s notion of listening-rhetoric: looking for similarity of thought before blindly reducing and striking back with counter-arguments.

“Pursuing truth behind our differences,” is how Dr. Booth would say it.

One thought Mr. Harris puts forward is that rather than forcing a text to get to the point, it might make better sense to ask, “What is the author’s project?” This question is about the intention behind the text. What was this poem/movie/op-ed/monologue/sermon/text trying to accomplish? Why did [whomever] write it and what did they hope to persuade the reader of? After you guess at that you stand a better chance of understanding their point (if there is one point). And this is particularly helpful when an author is presenting multiple points—like in the back and forth of a conversation, when someone is trying an idea on for size. This appeals to me because I’ve sat through too many meetings and preachments where the speaker’s point was forced out of a text that had zero to say about the topic. I have also been guilty of this violent approach to a text.

I like the notion of being generous with the texts we read and the conversations in our lives.

I am also persuaded we are all in the business of persuading each other all the time. We all have projects.

###

Image Credit: Kirk Livingston

Copywriting is a Full-Contact Sport

James Young: a Technique for Producing Ideas

Today we discuss Mr. Young’s book on how to have ideas. It’s an old book and disregarded by some of my copywriter/art director friends. But I come back to it again and again. I like how Mr. Young serves up the notion of a way to go deeper than our immediate surface reaction. I like the book because he provides signposts and mile-markers along the road of getting to the heart of a notion.

To me, copywriting is a full-contact sport. Here’s what I mean: ideas do not come from sitting in a dark room and thinking deep thoughts. That is called a “nap.” Ideas come from a mind-body connection. Copywriting starts with gathering materials (Young’s Step #1) and then writing out the connections between those materials and the target audience’s problem or perceived need (Young’s Step #2—Masticate). This mastication or digestion step involves pages of false starts and headlines and mind-maps. It involves shuffling index cards and drawing with crayons on the walls/arms/shoes and many dumb sketches. It involves telling others your nascent point and watching their reaction (“What the…. Huh? Get away from me.”)

I particularly love Young’s Step #3—Walk Away. It’s when I go for a bike ride or a jog or a walk. Or lunch. Anything other than the problem at hand. And then—Behold—the solution pops into being. Fully-formed. Sorta. Sometimes it’s an ugly baby and needs, shall we say, a trim. But out of this process come useful ideas that get to the heart of the matter and may—just possibly—cut through clutter rather than add to it.

Check out Maria Popova’s take on Young’s technique here.

###

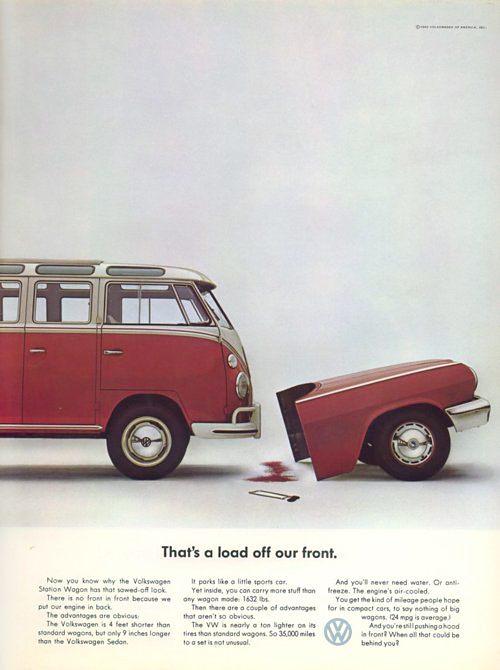

Image via Copyranter

By The Lake

Summer will appear, one fine day.

File under: Travel theme: Statues [of the West}

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

“Do You Know Bob? You Should Meet Bob.”

Listen when your friend says this.

After your friend hears what you have to say and then responds with,

Hey—have you ever asked Judy about that? Because Judy talks constantly about that very thing.

Listen.

And then go meet Judy. Or Bob.

Because a friend’s recommendation—after seeing a similarity or spark of sameness—can be telling. The connection your friend saw to make the recommendation implies you have something in common with this other person. Some way of thinking that will form a third-rail for communication.

And that is worth following up on.

I think Keith introduced me to Steve—likely through some offhand comment. Steve is a C-suite communication guy who also teaches and we talk about communication strategy, corporate life versus freelance life, life in agencies and the demands of teaching. I’ve had coffee with Steve a couple times and I honestly don’t think I could find more wisdom and excellent advice and weathered perspectives if I paid Seth Godin’s consulting fee for an hour of talk.

We have no clue what might happen with a connection. No idea where a conversation will go.

This remains amazing to me.

###

Image credit: Garry Winogrand via MPD

Boss: With this ping, I have now pled

Think Globally. Act Tactically.

Sometimes we just do our job.

Sometimes we think bigger thoughts and help our boss sort out what next—long before being asked.

I maintain our best work comes from that place where we think strategically and act tactically. Our best work comes from big thinking harnessed to this moment’s need.

Today in our copywriting class we talk about relationships with clients. My line on this is to cherish, honor and protect your client—which starts to sound like a marriage—not quite the right analogy.

Then again, maybe it isn’t far off.

Clients are people who trust us to handle their message. They’ve hired us to do something they cannot do. This is a privilege. Our favorite clients know the best work comes from well-articulated need and parameters followed by the freedom to go and do. And sometimes our clients depend on us to help articulate those needs and define those parameters—simply because we get very close to the need.

This is where the copywriter’s outside perspective helps immensely. It’s also where we deploy our skill of listening into the deep waters of what our client eats/sleeps/breathes/knows. Because sometimes what seemed like only tactical work can turn into an opportunity even the client didn’t realize was before them. And we need to say so.

Such is the opportunity with collaborative teamwork and trusting work relationships. And that’s why it is important copywriters always think Grande or even Venti rather than Short.

Here’s to clients! (Jaunty raising of the ice water glass)

Long may they…, well. Hire.

###

Edward Hopper: How to Talk to Yourself

Can a conversation result in art?

The answer can only be “Yes!”

Not every conversation, mind you. But some will.

Last weekend Mrs. Kirkistan and I (plus our art-student daughter) wended our way through the sketches and drawings by Edward Hopper currently on display at the Walker. As a nation we’re quite familiar with Mr. Hopper’s drawings and paintings—today they seem perfectly obvious explanations of life in America. But I was intrigued by how he got there. What was his process for producing such enduring images? How did he see what he saw?

His sketches look like conversations with himself. Look how he developed the frame for his (well-beloved, much parodied) Nighthawks at the Diner. His sketches add layer to nuance to layer. It’s almost as if he were explaining something to himself with one approximation and then another and then another. Sort of like conversations with our best friend where we allow each other to say it wrong even as we pursue saying it right.

Hopper was a man given to observation and keen on interpreting detail. With quick strokes he captured form and mood and motion. And there’s no question he had an eye for the ladies:

Hopper seemed to never stop observing and capturing. Again and again and again. He spent hours sitting at favorite locations and sketching and perhaps waiting. This quote from Mr. Hopper hints at his process:

My aim in painting is always, using nature as the medium, to try to project upon canvas my most intimate reaction to the subject as it appears when I like it most….

I’ve been a fan of sketches for some time because they give a behind-the-scenes picture into how someone’s mind works. The Hopper exhibit at the Walker does not disappoint. And I cannot help but think how sketches provide such a rich analog to our collaborative conversations.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston photos taken at Edward Hopper exhibit, Walker Art Center

If you bet, bet with your head.

Or just don’t bet.

It’s still a gamble, after all.

But always use your head.

###

Copywriting Tip #1: Love the Study

As an undergrad studying the general courses before getting into the nuts and bolts of my major, I typically looked for the easiest way to get homework done. I wanted to spend as little time on it as possible. Homework simply was not that interesting.

But in my major, that notion got turned on its head: I wanted to spend as much time as I could gather because the topics were fascinating. Becoming fascinated and digging deeply are prerequisites to making something remarkable to someone else.

Making something remarkable is the work of the copywriter.

We’re at the threshold of another copywriting class so I am bringing back this older post to get at why it is critical we go deeper than first impressions. We all want to take the easiest path, but the easy or obvious solution—the one you developed because you waited too long to start the assignment and it is now due—is not the one you’ll want to show someone else.

“Easy” and “obvious” do not produce remarkable results.Remarkable requires going deep.

###

In Freelance Copywriting (Eng3316) we’ve started producing work in earnest and every week (including tomorrow) another student piece moves into their portfolio. All the students have signed up for work they’ve never tried before—ad concepts, radio scripts instructional booklets, and many other forms. All according to where their writing passions are leading them.

In Freelance Copywriting (Eng3316) we’ve started producing work in earnest and every week (including tomorrow) another student piece moves into their portfolio. All the students have signed up for work they’ve never tried before—ad concepts, radio scripts instructional booklets, and many other forms. All according to where their writing passions are leading them.

One thing I love about copywriting is learning new stuff. Whether it’s asking a doctor questions during brain surgery or watching a silicon wafer get doped and fired or learning about the medicines Lewis and Clark used (forced marches and blood-letting seemed to resolve a lot of their ailments). There is no end to fascination with how the world works. Putting what I learned into words (and images) electrifies the whole task: spooling out my argument and helping show why anyone would care what the patient said while the doctor probed his frontal lobe, or why ramping…

View original post 184 more words