Archive for the ‘art and work’ Category

Stop-Action Living & How to Pay Attention

Jean Laughton’s Mythic West Borders Her Real West

Put a frame around the scene before you and the scene changes. The frame creates distance from the action, which is both useful and off-putting.

Useful in that the frame helps you stop and see what is going on. Moving parts fall (momentarily) silent and you are released to think critically about the action. Note that critical thought need not be negative or a complaint or a sardonic aside. Critical thinking can result in even more whole-hearted agreement with the action. Critical thinking can also lead to backing away from the action.

Off-putting in that the frame truncates the scene and isolates it from everything else. Off-putting because the people in the scene see the camera and note you’ve switched from action to observer, which most of us find discomfiting. Pick up a camera or sketch pad and you’ve suddenly marked yourself as something other than what is happening right here and now. Pick up a camera and watch people freeze or back away.

Edmund Husserl (that 19th century mathematician/philosopher/phenomenologist) talked about leaving the “natural attitude” and bracketing his experience to come to fully understand/appreciate the experience. Actually, Husserl advised breaking with the natural attitude and bracketing experience to get on with his phenomenological work. Henri Cartier-Bresson always used a 50mm lens to capture the surrounding action, so his audience could see the central action in context and form stronger conclusions. Damon Young, in his Distraction, cites Henri Matisse in explaining how art became his way of looking at the world:

“I am unable to distinguish,” he wrote in 1908, “between the feeling I have for life, and my way of expressing it.”

Any way you cut it, paying attention and making your experience available to others are somehow linked. In Jean Laughton’s work, she takes her camera in the saddle and documents life as working cowgirl. The images she creates are mythic and telling and honest.

Walk through a few of Jean Laughton’s images and you’ll be glad she is paying attention. Laughton seems to have found a way to live in the scenes even as she brackets them. Her frames seem to not take her away from the action. The result is both memorable and accessible.

###

Image credit: Jean Laughton via Lenscratch

College Majors to Avoid + Rebuttal

And back to the work itself

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Good design often has this effect on me: it makes me want to find and do the work I am meant to find and do. Moving quickly through the many architecture or art or photography blogs out there also reminds me of what vision looks like when carried out. Vision alters our perceptions of the physical world and sometimes alters the physical world itself. And that is no small thing.

Yesterday I found myself in disagreement with the Burnt-Out Adjunct (whose too-infrequent posts I eagerly await and enjoy) who wrote that liberal arts studies should be more corollary than central to a college degree. Pisspoorprof was reflecting on another of these “ten worst” articles that pop up from time to time. This time it was Yahoo! Education touting the Four Foolish Majors to Avoid if you are trying to reboot your career.

Liberal arts degrees were the #1 opportunity killer with philosophy a close #2 opportunity killer. By the way, I cannot help but note that the entire article is an advertisement for the continuing services of Yahoo! Education.

As a holder of an undergrad degree in philosophy I both agree and disagree.

- Yes: no one hires a college grad to resolve deep-seated teleology questions (one does that on one’s own time). But to his credit, the VP at Honeywell who gave the OK to hire me (lo these many years ago) did question my stance on freedom vs. determinism.

- No: How about granting a bit of perspective? We need people who can think outside the present job parameters. And we desperately need people to challenge those parameters. Educating people to acquiesce by default is not what we need (though it is a short-term path to cash). Liberal Arts (and especially philosophy, let me say) can help this happen. Yes that sounds like the standard line from any college admissions staff says. Yes it is what professors say as they pass each other in the hallowed halls. No you don’t need a college degree to challenge the system, make a million bucks, make a difference or be homeless.

But studying things that don’t make money has a way of making us more conscious of all that is going on around us. Will it eventually make money? Maybe. Maybe not. But we need people with larger vision who can paint or write or photograph or build a different way of looking at things—however that happens.

What do you think?

###

Image credit: Studio Lindfors via 2headedsnake

Do a Dumb Sketch Today

Magnetize Eyeballs with Your Dumb Sketch

As a copywriter, I’ve always prefaced my art or design-related comments with, “I’m no designer, but….” I read a number of design blogs because the discipline fascinates me and I hope for a happy marriage between my words and their graphical setting as they set off into the world.

As a copywriter, I’ve always prefaced my art or design-related comments with, “I’m no designer, but….” I read a number of design blogs because the discipline fascinates me and I hope for a happy marriage between my words and their graphical setting as they set off into the world.

But artists and designers don’t own art. And I’m starting to wonder why I accede such authority to experts. Mind you, I’m no expert, but just like in the best, most engaged conversations, something sorta magical happens in a dumb sketch. Sometimes words shivering alone on a white page just don’t cut it. Especially when they gang up in dozens and scores and crowd onto a PowerPoint slide in an attempt to muscle their way into a client’s or colleague’s consciousness. Sometimes my words lack immediacy. Sometimes they don’t punch people in the gut like I want them to.

A dumb sketch can do what words cannot.

I’ve come to enjoy sketching lately. Not because I’m a good artist (I’m not). Not because I have a knack for capturing things on paper. I don’t. I like sketching for two reasons:

- Drawing a sketch uses an entirely different part of my brain. Or so it seems. The blank page with a pencil and an idea of a drawing is very different from a blank page and an idea soon to be fitted with a set of words. Sketching seems inherently more fun than writing (remember, I write for a living, so I’m completely in love with words, too). Sketching feels like playing. That sense of play has a way of working itself out—even for as bad an artist as I am. It’s that sense of play that brings along the second reason to sketch.

- Sketches are unparalleled communication tools. It’s true. Talking about a picture with someone is far more interesting than sitting and watching someone read a sentence. Which is boring. Even a very bad sketch, presented to a table of colleagues or clients, can make people laugh and so serve to lighten the mood. Even the worst sketches carry an emotional tinge. People love to see sketches. Even obstinate, ornery colleagues are drawn into the intent of the sketch, so much so that their minds begin filling in the blanks (without them realizing!) and so are drawn into what was supposed to happen with the drawing. The mind cannot help but fill in the blanks.

The best part of a dumb sketch is what happens when it is shown to a group. In a recent client meeting I pulled out my dumb sketches to make a particular point about how this product should be positioned in the market. I could not quite hear it, but I had the sense of a collective sigh around the conference table as they saw pictures rather than yet another wordy PowerPoint slide. In fact, contrary to the forced attention a wordy PowerPoint slide demands, my sketch pulled people in with a magnetism. Even though ugly, it still pulled. Amazing.

###

Try this: Be Ionic, Iconic and Ironic

Disturb Someone Today

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts manages to be ionic (columns), iconic (yes, the columns again) and ironic (colors on columns–really?)

It’s all in the mix. Start with an ancient form: a note, a letter. A poem. An email? Get the form just right and let it carry all it was meant to carry. Then bring it into today with an element that steps outside that form. The MIA does it with colored lights on the ionic pillars with are also iconic. Is the result beautiful? Not exactly. Several of us have thought a lot about whether those lights are right or wrong. We decided they are ironic.

That’s why I’m so fond of the cards turned out by Zeichen press. Old form. Old cold type. I’ve worked with quoins and frames and rollers that spread ink across a platen. Everything about the process shouts “old.” But the messages are anything but old. Their cards disturb even as they console or encourage.

How can you disturb someone’s attention by mixing up an old form with something of today?

###

Hopper Early Sketches

Where does an idea come from?

Sketching shows the beginning of an idea.

Over at lines and colors, Charley Parker highlighted an exhibit at the Whitney that promises a look into Edward Hopper’s process.

###

Why I Like the Dumb Sketch Approach to Life

The Lure of Rough Drafts, Quick Observations and Badly Drawn Lines

I made this dumb sketch when visiting our son working in Madison, Wisconsin. Madison holds lots of memories for Mrs. Kirkistan and I: we went to school and met at the UW, we met amazing people who remain friends today decades later and made big directional choices. It was a place for fiddling with and setting trajectory—it still is that today.

Like most summer weekends there was a concert on the Memorial Union Terrace. This jazz festival (see dumb sketch) was running all weekend. These days it seems all of Madison turns out at the Terrace.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

Yesterday I quoted photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson likening his camera to a sketchbook: it helped him instantly sort the significance of an event. And that is exactly what sketching does: it is an entirely imperfect representation (at least my sketches are) of what we all saw. Dumb sketches invite participation, which is why my colleagues and I often employ dumb sketches as we work through a direction with our clients.

One of the functions I relish as a copywriter is this responsibility to provide a rough draft. The rough draft is this work of writing out the position or power of my client’s product or service so others can respond. Or sometimes I’m summarizing and sharpening the science behind a product so we can see more clearly why it is important. Rough drafts are both right and wrong at the same time. The power of the rough draft is to set a thought out in the open where others can reach and tag it. After all, you can’t change something that doesn’t exist. The point is collaboration: how is this right? What do we know that can make this more right?

Saying aloud what we know and what we believe is the verbal equivalent of a rough draft. And saying aloud what we know is more than helpful. It is part of the human condition and not to be missed. Our conversations reveal who we are and what we know even as they and invite participation. Getting it wrong sometimes is part of the deal.

That seems like a good approach to life.

###

Image credit: Kirkistan

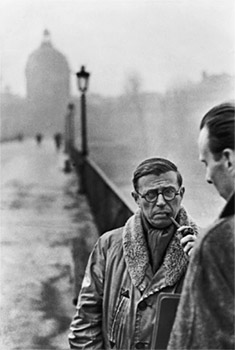

Cartier-Bresson: Zoom Lens is the Work of the Devil

To See. To Learn to See.

I’m not sure if Henri Cartier-Bresson actually said that about the zoom lens, but it would fit with his aesthetic. He spent his life getting close to his subjects with a small Leica and its 50mm lens (which he used all his life). That camera and lens brought him in close and kept him there. Someone recently described the big zoom lenses available today as akin to hiding and shooting as a sniper.

What impresses me about the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson is his ability to capture something deep in people. A moment of reflection. He called it “the decisive moment” and it was gone as quickly as it appeared. Cartier-Bresson could irritate people because he would sometimes take a photograph before his initial bonjour. But he also spent time just hanging around with his camera. People grew used to seeing it (the Leica) and him and he was quick to bring it up to his eye and put it down again: no big deal.

In my quest to learn to see, Cartier-Bresson is a valuable guide. He photographed lots of famous folks (thinkers, artists and politicians—he shot Gandhi 15 minutes before Gandhi was, well, shot) and he captured lots of regular people—in a way that reveals a stunning beauty. Here’s a lovely collection of his Magnum photos. Two quotes from this remarkable man:

To me, photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event.

For me, the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity, the master of the instant which, in visual terms, questions and decides simultaneously.

Seeing takes work and practice.

###

Image Credit: Henri Cartier-Bresson

A Stage for Prince and a Grave for Tiny Tim: What Music Says About Minneapolis/St. Paul

Minnesota Theology of Place: Live Performance Matters in the Twin Cities

If one were rooting around trying to sort what values and practices make a place unique, music would be a good start. Jon Bream, music critic for the StarTribune recently wrote about why Minneapolis/St. Paul has become a home away from home for many rising musical stars. Bream cited four very different artists/bands (Dawes, Brandi Carlisle, Eric Hutchinson and JD McPherson) and noted how audience turn-out in the Twin Cities fuels these artists. Mr. Bream commented:

The key factors are open-minded audiences who love live music; a variety of venues that help artists build a career, and support from radio and other media.

The Current, of course, is a vocal apologist for the new music that grows outside the mainstream (and often, eventually, moves mainstream). I would argue the Cedar Cultural Center has been doing that same good work for years and years. Then there are the high profile, historied venues like First Avenue that have helped audiences and artists form connections. There are many more, of course.

A few days back I wondered aloud what a theology of place might look like for Minnesota. I cited all sorts of influences that would speak to that question.  Developing a theology of place is to look at a community from a perspective unfamiliar to most of us. It is a perspective that begins with a commitment to belief in God and then wonders what God is doing in that place, among those people, through their history. It’s a deeply rooted sort of activity: digging down and back to find out who did what and asking what they thought when they did it. And then asking how what they did affected others. And also asking how their belief structure enabled the outcomes before us.

Developing a theology of place is to look at a community from a perspective unfamiliar to most of us. It is a perspective that begins with a commitment to belief in God and then wonders what God is doing in that place, among those people, through their history. It’s a deeply rooted sort of activity: digging down and back to find out who did what and asking what they thought when they did it. And then asking how what they did affected others. And also asking how their belief structure enabled the outcomes before us.

To be intensely local for a moment, what would a theology of place look like for the Twin Cities—just starting with music? Bream’s observation of how audiences love live music fits with the general interest in theater in the cities. Apart from the Guthrie, there are dozens of small theaters in the cities that are producing memorable performances. Does a population that welcomes new music and new artists and helps support dozens of very small theaters mean we like the notion of “live performance” and see it as a way to connect with each other? Maybe we like to see our meaning made right before us—because we know that an audience is part of the meaning making.

Maybe the notion of a fondness for live performance accounts for the 20,000 people who showed up in St. Paul’s Lowertown last weekend for Northern Spark. And maybe our love for live performance accounts for the bike and craft beer cultures that are all about connecting (this year’s Artcrank pulled in an overflowing crowd).

Not that we’re unique in these things—but there’s something happening. As a curious person and one with belief in God, I cannot help but wonder what it means—even as I rejoice in the vibrant commitment to connection.

###

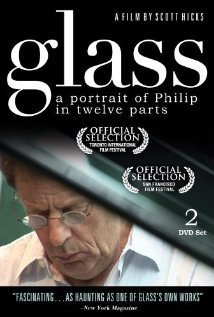

When I get discouraged about writing, I think on Philip Glass

Just Thick-headed Enough

Philip Glass is known for repetitive structures in his music, among other things. Mr. Glass is famous (ish) today and you hear his music most commonly on film soundtracks. But not everyone likes those minimalist, repetitive structures (some members of the politburo of Kirkistan will sit for only limited doses of Mr. Glass’ music).

The 2008 documentary about Philip Glass contained quite a few unguarded responses to his music. Watch the film for the exact quotes, but the general sense people communicated to Mr. Glass as he developed his unique style was something on the order of “Please go away” or “Please stop playing that” or “I think we’ve heard enough of that. Can you do something different?”

In a 2009 Esquire interview, Mr. Glass, said this about his resolve:

When I struck out in my own music language, I took a step out of the world of serious music, according to most of my teachers. But I didn’t care. I could row the boat by myself, you know? I didn’t need to be on the big liner with everybody else.

I often think of Philip Glass when I get discouraged about writing.

Writing is difficult, so says anyone who writes. Just like with anything worth doing, there are all sorts of missteps and problems and wrong directions and mistakes involved with getting a thought on paper. And then there is the problem with the audience. I might call it the Glass Problem: prolific production of something no one wants.

But one continues forward. Despite responses. One must be just thick-headed enough to continue sorting out what it is one is trying to say. That’s what I understand when I think on Philip Glass: an infusion of courage to move forward despite all outward evidences that I really should stop.

###

Image credit: IMDB

Ray Becoskie: The Solution Should Always Have a Flag

Because There’s a Pistol in Her Purse

More Art-A-Whirl aftershock.

A few days back I wrote about Cody Kisel’s vision for consumerists. On that same floor of the massive Northup King Building, I had a hard time tearing away from Ray Becoskie’s paintings. Mr. Becoskie’s work transmits a wry humor and a fair amount of joy along with the puzzle of his titles.

Here’s Becoskie on his process:

The work is generally constructed from three things. Things I know, things I believe, and things I make up. I get them all together in a room and I do my best to document the conversation that happens.

###

Image credit: Ray Becoskie