Archive for the ‘Collaborate’ Category

“Thou Art a Cad, Sir.”

May You Have Interesting Colleagues

This is the time of year when people refer to that old Irish blessing (about the road rising up and so on). But here—stuck in the middle of the work week—I want to offer you a more contextual blessing: the people around you.

Well, maybe not everyone.

But often there is someone you come in contact with who is, well, delightful. Their sense of humor, the wacko things they say over the cubicle wall, the inappropriate things they do in department meetings. The fact that they will trim your hair in the back room when the director is out of the office or dump Vaseline in the bigshot’s duffle bag or instigate rebellion at the slightest provocation. [Am I sounding like a bad employee?]

In fact, it is typically the people around (the fun and interesting ones, anyway) who make work enjoyable.

Martin Buber made a point of differentiating between how we treat objects (“I-it”) versus the way we treat people (“I-thou”). One of his points was that we should never treat people as objects: ordering them about as if they had no will of their own. Instead we should engage with each other. That’s what humans do.

Of course that very object-treatment is one of the primary sins in many of our corporations, where people become known as “human capital.” Churches are not so different when they refer to congregants as “giving units.” Hey—we even take cues from our cultural bosses and call ourselves “consumers.” Our language makes no attempt to mask this object-laden perspective.

But no so with interesting colleagues, because of our connection with them. Because of conversations you’ve had with them (some even soul-baring), because you’ve talked shop and lamented death and rejoiced in birth together, you get to know each other as fully-human. Trust and connection fit in here. And the ability to say anything.

The ability to say anything and still be heard and respected, that is the fullness of connection with another Thou.

May the “Thous” rise up to meet you today and this week.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

How to step into a conversation. And when to step out.

Can presence and distance live in peace?

The philosopher, the writer, the journalist—and many others—work at cultivating distance in relationship even as they stand in the present.

Why do that?

The work of analysis, of illustrating via story and reportage all require distance for the facts to sort themselves. Just like the passage of time has a way of revealing what was important ten, twenty and two hundred years ago. Just like the artist learns to imagine a two-dimensional plane to begin to make marks with/on their media.

Distance starts to open a way forward by helping us see differently. Presence demands attention—that’s the human piece of empathy and mercy. Sometimes we need to slip from present to distant and back again. All the while avoiding absence.

My conversation with the hospice chaplain reminded me of the help a bit of distance brings to sufferers and those in grief. The person slightly distant brings a perspective the sufferer may need to hear, though that perspective may not be immediately welcome. Best if that slightly distant perspective comes wrapped in empathy and mercy.

But even at work we can cultivate a bit of distance for the sake of clarity. When the boss pontificates it doesn’t hurt to ask why she does so and what rhetorical goals her sermon serves.

And even at home we can mingle distance and presence: staying present with family (versus attaching to whatever screen or podcast holds our attention) is the first order of business. But we bring perspective when we step back.

We need presence and distance to move forward.

Absence rarely aids progress.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

3 Lessons I Learned Hanging With 70 Artists

See. Do. Share.

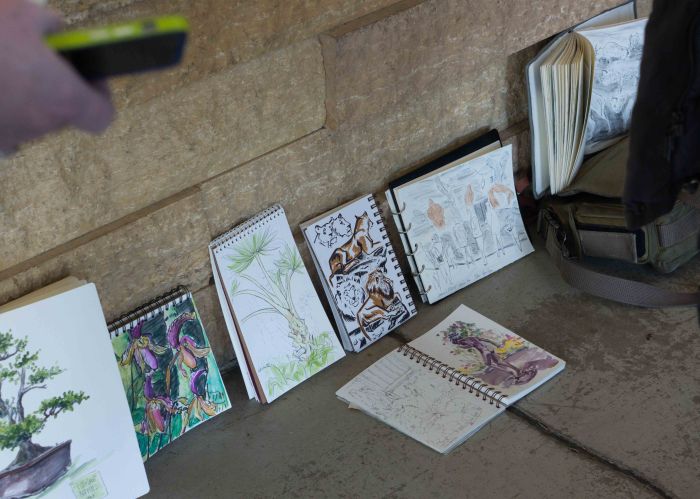

A group of artists in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area gathers monthly to sketch. They call themselves MetroSketchers. These are talented people with facility for capturing life on a page. Yesterday I showed up to sketch alongside them at the Como Zoo in Saint Paul.

- Look To See. It’s easy to spot these sketchers in the crowds at Como. They are the ones balancing a sketchbook, and possibly watercolors or an arsenal of color pencils. They are the ones looking up and down and up and down at the very scene I dismissed with a quick glance. It’s the lingering look with an intent on capturing what they saw that was meaningful to me. Sketchers linger far longer than the causal passer-by. They must.

- Do It. Right now. That’s it—just get it on paper. Whatever you can. This is a lesson that carries over for me from writing. Do it badly, but just get one good stroke on the paper. One good mark among many bad marks. My great contribution to the day’s artistry was the Polar Bear Butt (the only animal who insisted on posing). Bad as it is, it is still a move toward representation.

- Share It. These uniformly talented people were also great encouragers. To a person they were all about what you saw and the marks you made in response. They found good stuff to say even when good stuff was pretty well hidden behind lots of not-good stuff. They also loved to talk about paper weight, the best inks to use, how small they can pack a watercolor kit and, “…here, let’s just walk through my sketchbook together.”

I spoke with many during the sketching and they were more than happy to show what they were doing, to describe how they were seeing and to talk about the difficulties in representation.

More than one sketcher expressed delight in what they were seeing—and if that is not a perfect reward for the interaction between drawing and seeing, then I don’t know what is.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

We’re Bigger Than This

Helping Colleagues See the Larger Story

Bad manners and ill-treatment make headlines in personal conversations at most of the companies I’ve worked for. Just like in our newspaper or aggregated news sources online. People often say they wish the newspaper published good news, but they would not read it if it did. Good news—things going right for a change—few have time or interest for that.

Naturally this is so: stories of the people around us always take top billing in our conversations. Family, colleagues, neighbors, we love hearing what each other did and we love to relate a story about someone else, especially if funny or it has some emotional content that will get a reaction. It is the emotional content, whether funny, sad or repugnant that we really want to get across to each other.

It is our way of connecting: we want to stir a reaction.

It takes a concerted effort not to talk about the people who are not there. Leaders see personal interactions as an opportunity to steer interest toward something larger. But that larger thing is not the mission statement produced by the top brass or Human Resource, which is typically a lifeless bit of plastic. The real stories, the ones that make leaders out of ordinary citizens, are those stories where something of the corporate or group mission has made its way into and through an ordinary life.

One boss related a conversation she had with a far-away department. The department director praised specific people on the team and told of specific details that helped their group move forward. When our boss told this to the team in casual conversation, people blossomed.

We need more connection with larger mission—even if it seems hoky at the time. And we need less stories about how bad/abnormal/demonic are the people not present.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

To Flee Corporate Dysfunction or Not?

Where will you run?

My friend just quit her corporate job. She does not have another job.

“Too much dysfunction,” she said. “Why spend my days in a cube, following through on poor choices our leaders made under the guise of collaboration? There’s got to be a better way.”

“I hope you are honest in the exit interview,” several people said to her. Other top talent had quit as well and those remaining cherished a hope of productive work.

Every company has these bouts of employee-flight. Maybe the department director is a megalomaniac. Maybe the boss simply doesn’t know what to do next and is not open to advice. Maybe the department trolls rule the roost. Every so often dysfunction catches up with a department or company and talented people throw up their hands and march to the exit. It is more common when the economy is on the rise, but even in a down economy, talented people choose flight over fight, even with no job on the horizon.

So it is with my friend.

She had had enough and hoped to parlay her high-end employee history into a freelance life. I often talk with people considering this move. What I liked about this conversation was that my friend could identify a few key skills and passions that she wanted to pursue. And she had already begun to push on these passions. She knew what she wanted to build next. So her “I quit!” was less about fleeing and more about “now is when I do this thing I love.”

Because, the truth is, you can never be entirely rid of dysfunction.

“Why is that?” you may ask. (I can hear you.)

It is because you bring it with you. Disagreeing and disagreeable. Seeing issues from your personal, rigid perspective. Combative. Megalomania. These seeds are planted in every one of us. Sometimes it doesn’t take much to cause them to flower. A good conversation harnesses different potentials in those seeds and helps us move forward. A dysfunctional environment feeds the bad seed and strife rises to the surface.

Such is the human condition.

But moving forward toward our passion, finding time to do those things we love—the things we are meant to do, even if no one else cares—that feeds the productive functional seeds in us.

Is there a way to do the things you were meant to do today—right now—even as you wade through the current dysfunction?

That is the question.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Josephine Humphreys: When writing from the center of things

The world keeps aligning with what I just wrote.

Interviewer: When you’re writing, is it that you notice things more acutely?

Humphreys: Yes. You notice everything, and everything seems to be full of meaning and directly centered on the thing you’re writing about. I heard E.L. Doctorow say something like that—that when you’re writing, all experience seems to organize itself around your themes, which can give you some really strange feelings of coincidence and ESP. You start to think you’re onto the secrets of life.

–Josephine Humphreys, quote by Dannye Romine Powell, Parting the Curtains: Interviews with Southern Writers (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 1994) 192

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

The Lamp Repair Man and the Factory Owner

How do business and passion mix?

A man had a small business repairing oil lamps. He repaired wicks or refilled lamps with oil—whatever was needed. He took his cart to different neighborhoods and called out for business: “Lamp repair” and “Fix your lamp.”

When people brought their lamps to the man, they would watch him trim or replace the wick, refill the oil and polish the glass. The man had a quick rhythm to his method: he sang a song softly that guided him through his process of checking each lamp. The man was unfailingly kind and full of joy and neighborhood kids loved to watch him as he worked. He would often say providing light was what he was meant to do.

One day a factory owner was home for the morning. He was feeling a bit unwell from celebrating late into the night after successfully negotiating deep concessions with the largest union at his factory. When he heard “Lamp repair” shouted outside and remembered his children exclaiming over the charms of the lamp repair man, he stood and picked up the lamp he had been reading by and made his way outside.

The lamp repairman took the lamp and quickly sang his song to himself as he checked it over. Then he trimmed the wick, polished the glass and handed it back to the factory owner since it was nearly full of oil.

“What do I owe you, Mr. Lamp Repairman?” asked the factory owner.

“Oh, nothing,” said the man. “That took no time.”

The factory owner would not have it.

“But surely your time is worth something,” he said. “Surely you have some small fee for checking and trimming and polishing. I own a factory and I must pay for every bit of my employees’ attention.”

“Well,” said the man. “I’ve found that I am most interested in how light works and what it provides. I love a well-lit page when I read and I am eager for good lighting for others. So it actually rewards me when I can get someone’s lamp working well.”

“But can you live on good feelings?” asked the factory owner. “Do your good feelings buy potatoes or flour? Can you pay your landlord with good feelings?”

“True,” said the man. “Good feelings don’t buy much in the open market. But good intentions find their way back. I have found that helping those along my regular route helps build my business. People return when there lamp needs repair because they know I’ll be fair and they know I’ll do my best to get their cherished lamp working. You give a little, you get a little.”

“I see,” said the factory owner. “Give a bit away free and then get rewarded with loyal customers. Good strategy.”

“Yes,” said the man. “It was a good strategy for many years. But today I am actually well-provided for. I’m not rich, but my wife and children and I have enough. I actually charge only rarely because I don’t need to and because I am interested in the lives of these customers who have become friends over the years. Children and grandchildren of long-time customers bring out their lamps. I am eager that they have enough light for the many books they read and drawings they make and conversations they have.”

The factory owner took his lamp and walked back to his home, thinking back to the work he did that started his own factory.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Pat Conroy: How to tell when the story has started

Sometimes Mr. Subconscious arrives at the work site before Mr. Conscious

I think dreams are very important. I think dream journals are important. Extremely important. I have dreamed the ends of books. When I start dreaming about the book, I know it’s now starting.

–Pat Conroy, quoted by Dannye Romine Powell, Parting the Curtains: Interviews with Southern Writers (Winston-Salem, NC: John F. Blair, 1994) 51

I can’t vouch for dreams, but I cannot help but notice how Mr. Conroy’s stories seem to start without him. Writing is hard work, but there’s no denying these bits where the subconscious fills in gaps at the work site before you even arrive.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

How to Anticipate a Thaw

Sometimes life mirrors fiction

My client needs a strategy for their online presence.

They know their presence appears text-heavy and pedantic, making them less attractive to the new audience they seek. My client’s online presence must quickly inform the querying audience why they should care, but this message needs to be packaged with a color palette and intuitive organization that say “Come in!” long before the audience gets to the headlines, let alone body copy.

All sorts of off-the-shelf tools can make that happen these days. WordPress has a number of themes that can invigorate tired old websites.

But what I’m interested in is the engagement-promises my client can make that are deeply true. The organization itself is on the cusp of change and their online presence is a first new thing to present a refreshed vision. As such, their presence needs to be aspirational (“Here’s who we want to be”) but also rooted in long-held values. Their new presence needs to reflect the hard-won, chiseled facets they have come to love—facets that may just present new ways forward.

When I get stuck writing a piece of fiction, I go back and see what my characters have already been saying and doing. And then I retrace their steps along a new trajectory. And that is exactly what my client needs.

This is a team effort situated in real life. And this team effort will retrace and map and begin to outline a new trajectory. This team hopes to generate a conversation that precipitates a thaw after a long winter. We hope this conversation will pull in those who have long been hibernating.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston