Archive for the ‘Collaborate’ Category

Beware the Information Hoarders in Your Office

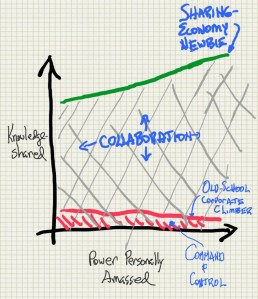

Collaboration opens as the sharing economy pushes back into your organization

Old-School Corporate Climbers held information and doled it out on a need-to-know basis. Knowing secrets was their key to moving up and sometimes they purposely withheld information so you might fail/they might succeed.

Maybe you know someone like this.

But as we watch the sharing economy slip free of social media venues and push back into organizations (simultaneously raising the expectation of being heard), I expect we’ll see another kind of corporate operative: the sharer. Maybe I’ll call that person the Sharing-Economy Newbie. In this new world of sharing information, the Sharing-Economy Newbie shares information freely and in a way that allows others to collaborate. The power the surrounds them will not be command-and-control power, it will be the power that invites participation.

Then again, human nature being what it is, there will always be information hoarders. Old-School Corporate Climbers will always find their way. But if we intentionally build cultures that reward information sharing and collaboration, the organization, its mission, and humanity are the big winners.

Maybe there are some who prefer a command-and-control culture of being told what to do at every turn, but there will be fewer and fewer every year.

###

Dumb sketch credit: Kirk Livingston

Clothe Your Team with Inspiring Briefs

Creatives are natural problem-solvers. Start them with a tantalizing puzzle to solve.

In stark contrast to the meeting where the boss wanted creatives morphed into analysts, Adrian Goldthorpe (Lothar Böhm London) has such faith in the creative process he thinks creatives are proper problem solvers. All they need is the right question, which turns out to be a really good puzzle to solve.

One Artist’s Solution: 262 Studios, St. Paul Art Crawl

The creative brief (as you know) provides a quick take on a new assignment. All too often the brief is prepared and presented as a sleepy, non-essential document. But for copywriters and art directors, that brief can and should be a vital link to starting with the right focus.

Goldthorpe laments the mindless filling of briefs and checking of boxes, which is how many creative projects begin. Instead, at a meeting in Moscow earlier this year, he recommended short, informative briefs that facilitate (versus block) creative solutions. The brief should succinctly answer five questions:

- What should the creative do?

- What do we want to achieve?

- Who is the audience?

- What is the brand proposition and how is that supported?

- What is the tone of the voice?

Of course there is more to say in a brief and we all experiment with different ways to communicate this information. But I like Goldthorpe’s succinct, concrete statement of the problem. It is enough information to provide a frame to begin the creative process.

Naturally the creative process is not just for “creatives” at an ad agency. Presenting our problem or opportunity for others to consider and collaborate with is something authors deal with, and parents and professors and bosses. And coworkers.

It behooves any of us to consider how we succinctly introduce a topic to others, especially if we want help.

###

Via POPSOP

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Why Medical Device Twitter Feeds are Boring

It’s because monologue can be enforced. Dialogue cannot.

Twitter is all about the quick, personality-laden human voice. Twitter carries truncated thoughts by design—more like a human talk—one thought at a time.

Official medical device Twitter feeds are boring because the communicators behind those feeds are trussed and bound by legal and regulatory protocols. The feeds are boring because competing lawyers have police scanner-like attention for claims that fall outside of the FDA-vetted matrix. And those feeds are also boring because many of us are not in chronic pain, or worried about going through airport security with a defibrillator or insulin pump or mechanical heart valve. If we were, we might get those medical device tweets instantly on our smartphones and find them very interesting indeed.

I’m glad those tweets are boring. I hope they continue to bore many of us because we don’t need the product.

How could medical device tweets be more interesting? Clearly the human voice must be involved. When Omar Ishrak tweets (@MedtronicCEO), the tweets are at times more personal, like when his daughter runs a marathon:

But generally medical device tweets lack the sound of the human voice. They tend to sound like monologue-rich press releases:

https://twitter.com/MDT_Cardiac/status/518422795077042177

Some companies don’t even try:

Ok: SJM does tweet over here: https://twitter.com/SJM_Media

Granted, medical device firms will never sass it up like DiGiorno pizza

But surely as we move forward into deepening inter-connections between professionals and regular humans, every company must find a way to sound human or risk not being heard.

Maybe that means special release from the legal/regulatory straightjackets for certain chatty employee/storytellers. Let them tell their stories in ways that are unique to them while continually repeating “My Opinion Only.” Can medical device firms institute official unofficial-storytellers? People who claim nothing but that they work at the place and this is what they see?

That might result in fun tweets that gather an audience and endear a company to a larger public.

The era of siloed communication is fading quickly in the rear-view mirror.

###

Ditch Your Job to Woo Collaboration

Sure it’s a mess. But it’s a glorious mess.

Focused, nose-to-grindstone is certainly simpler. Get it done so you can go home on time and watch TV.

Bring another person into your process and suddenly things get messy. You find yourself explaining rather than doing. And explanation is a time-sink—just like small-talk. Plus collaboration is not guaranteed: will you have to redo everything your collaborator attempted?

This is why students groan audibly when I introduce a group project in a writing class. Especially when their grade depends on successful interaction. They hate it hate it hate it.

And that is too bad. I’ve often wondered why we don’t teach collaboration alongside math and biology and writing and literature in grade school. But it seems collaboration is a thing you are primed for later in life, when you start to see you don’t have all the answers. It is a bent that takes root after we have an experience or two of utter delight at someone else’s contribution.

Wooing collaboration starts with shop talk: where you step out of your job’s established tracks and ask others about their experience. How do they do what they do? What do they delight in? Where does meaning enter into their work? Those answers play into our daily conversations. This is where we learn the eccentricities of our colleagues and see how they bring their diverse knowledge and experience to bear on the work. This is where we learn what it means to be alongside someone.

Just doing your job is isolating—especially when you think you have mastered it and have nothing left to learn. Inviting others into the thinking behind the job is incorporating. Yes it takes time and can be a mess, but in the end it is our connections that pull us forward.

How do you incorporate others into your work?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Bill Moyers: Serving “News” like the Butler Serves Tea on Downton Abbey

Do Not: Do Not Disturb the Master Class

All of us can stand a bit of disruption from time to time.

David Uberti wrote recently in the Columbia Journalism Review about PBS pulling ads from Harper’s Magazine as retribution for an article critical of PBS. PBS exists as a non-commercial, educational media channel. But the critical Harper’s article by Eugenia Williamson pointed out

And so, a fit of ad-pulling ensued. But it was this candid, PBS-critical quote from the patron saint of public broadcasting that caught my ear:

Wherever you land in your organization, there is some grand narrative at work that guides all involved. That grand narrative is often a good thing and useful. It is often laden with meaning that helps us do our jobs. But it is not a perfect narrative—never is—and parts call out to be challenged by practitioners.

After all, it is the disruptive conversations that lodge in our brain pans. Those conversations we cannot forget sometimes actually open our clam shell brains to something new. And that is the way of both innovation and truth-telling.

Many of us—especially the people-pleasers among us—are careful to assemble conversations that do not disturb the people around us. I am guilty of this. But truth-telling must necessarily veer from the party line.

If only because sometimes the party line veers from truth.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston