Posts Tagged ‘collaborate’

Beware the Information Hoarders in Your Office

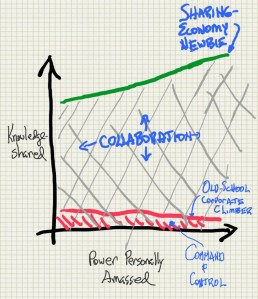

Collaboration opens as the sharing economy pushes back into your organization

Old-School Corporate Climbers held information and doled it out on a need-to-know basis. Knowing secrets was their key to moving up and sometimes they purposely withheld information so you might fail/they might succeed.

Maybe you know someone like this.

But as we watch the sharing economy slip free of social media venues and push back into organizations (simultaneously raising the expectation of being heard), I expect we’ll see another kind of corporate operative: the sharer. Maybe I’ll call that person the Sharing-Economy Newbie. In this new world of sharing information, the Sharing-Economy Newbie shares information freely and in a way that allows others to collaborate. The power the surrounds them will not be command-and-control power, it will be the power that invites participation.

Then again, human nature being what it is, there will always be information hoarders. Old-School Corporate Climbers will always find their way. But if we intentionally build cultures that reward information sharing and collaboration, the organization, its mission, and humanity are the big winners.

Maybe there are some who prefer a command-and-control culture of being told what to do at every turn, but there will be fewer and fewer every year.

###

Dumb sketch credit: Kirk Livingston

Clothe Your Team with Inspiring Briefs

Creatives are natural problem-solvers. Start them with a tantalizing puzzle to solve.

In stark contrast to the meeting where the boss wanted creatives morphed into analysts, Adrian Goldthorpe (Lothar Böhm London) has such faith in the creative process he thinks creatives are proper problem solvers. All they need is the right question, which turns out to be a really good puzzle to solve.

One Artist’s Solution: 262 Studios, St. Paul Art Crawl

The creative brief (as you know) provides a quick take on a new assignment. All too often the brief is prepared and presented as a sleepy, non-essential document. But for copywriters and art directors, that brief can and should be a vital link to starting with the right focus.

Goldthorpe laments the mindless filling of briefs and checking of boxes, which is how many creative projects begin. Instead, at a meeting in Moscow earlier this year, he recommended short, informative briefs that facilitate (versus block) creative solutions. The brief should succinctly answer five questions:

- What should the creative do?

- What do we want to achieve?

- Who is the audience?

- What is the brand proposition and how is that supported?

- What is the tone of the voice?

Of course there is more to say in a brief and we all experiment with different ways to communicate this information. But I like Goldthorpe’s succinct, concrete statement of the problem. It is enough information to provide a frame to begin the creative process.

Naturally the creative process is not just for “creatives” at an ad agency. Presenting our problem or opportunity for others to consider and collaborate with is something authors deal with, and parents and professors and bosses. And coworkers.

It behooves any of us to consider how we succinctly introduce a topic to others, especially if we want help.

###

Via POPSOP

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Ditch Your Job to Woo Collaboration

Sure it’s a mess. But it’s a glorious mess.

Focused, nose-to-grindstone is certainly simpler. Get it done so you can go home on time and watch TV.

Bring another person into your process and suddenly things get messy. You find yourself explaining rather than doing. And explanation is a time-sink—just like small-talk. Plus collaboration is not guaranteed: will you have to redo everything your collaborator attempted?

This is why students groan audibly when I introduce a group project in a writing class. Especially when their grade depends on successful interaction. They hate it hate it hate it.

And that is too bad. I’ve often wondered why we don’t teach collaboration alongside math and biology and writing and literature in grade school. But it seems collaboration is a thing you are primed for later in life, when you start to see you don’t have all the answers. It is a bent that takes root after we have an experience or two of utter delight at someone else’s contribution.

Wooing collaboration starts with shop talk: where you step out of your job’s established tracks and ask others about their experience. How do they do what they do? What do they delight in? Where does meaning enter into their work? Those answers play into our daily conversations. This is where we learn the eccentricities of our colleagues and see how they bring their diverse knowledge and experience to bear on the work. This is where we learn what it means to be alongside someone.

Just doing your job is isolating—especially when you think you have mastered it and have nothing left to learn. Inviting others into the thinking behind the job is incorporating. Yes it takes time and can be a mess, but in the end it is our connections that pull us forward.

How do you incorporate others into your work?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Your Office Needs More “Yes, and…” Men and Women

How to Grow Collaborators 1-2-3

- Share your first thoughts as if they were dumb sketches.

- Wait for—look for—and welcome reactions.

- Then say “Yes, and ….”

- Rinse & repeat.

You model commitment to collaboration by sharing your first thoughts. This dumb sketch approach to life makes you vulnerable and open to criticism. And there will be criticism. But vulnerability + time creates serious ballast around the notion of getting full engagement from all those around.

Your “Yes, and…” is the other shoe that drops to indicate you are also taking your colleagues seriously. It doesn’t matter whether your colleagues are bosses or employees, “Yes, and…” works up and down the corporate food chain. “Yes, and…” is your go-to reaction to ideas. People will gradually come to understand you think the world needs more ideas with legs and feet, ideas that accomplish stuff.

As kids we taunted each other with how sticks and stones break bones but words, well…you know. But it turns out words have a more complicated existence. In many respects, words have far more power than we ever guessed. And in this growing of collaborators, our words can make stuff happen out in the world (a “speech-act,” one might say). It only takes one committed collaborant (I think I just made up a word or re-purposed a French word) to begin to clear a safe space for collaboration. That space will invite collaborators, who become a nucleus to change a team, a group, an organization—and more.

How will you encourage collaboration today?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Do your best ideas come in two stages?

Maybe that’s where collaboration fits: between.

A story: In second grade we all had to talk about what we did over the summer. I wrote a story that included lots of driving to far-away parts of the U.S. I wrote about camping and swimming and mountains and lakes and trees.

When finished, I read it to myself and thought, “This is boring.”

So I went back at it and remembered mishaps along the way. Flat tires and people falling into lakes and instances of poor judgment from my brothers. Especially instances of poor judgment from my brothers. Then I started inserting instances of poor judgment all over the story and it got very, very interesting.

When I gave my speech to my second grade class, the instances of poor judgment got the biggest laughs.

Today I write stuff for a living, so I think in terms of drafts: There’s the rough draft, with all its heartache, hollering and hoopla just to wrestle a topic onto my screen. There’s the review with a stakeholder/client/colleague. Then there is the excellent revision. The goal is the excellent revision. But few people can begin with the good stuff that came out of the revision.

But you need not write stuff to realize that first ideas can often be improved by a clear-eyed, objective second glance. And often that clear-eyed glance, especially from someone hearing it for the first time, can tell you a lot about where the idea needs to go next. What your reviewer sees or doesn’t see, what causes them to pause, what causes them to guffaw, what causes them to restate or reread—all this is grist for the revision. And revisions are potent parts of the process.

With my clients I am very up front about wanting them to review a draft on the way to the final. And that is how I present it—I’ll write this thing and then you’ll look at it and give me your scathing criticism. And together we’ll move toward what we wanted all along. And the final will be that much better.

That’s what collaboration looks like to me: at least a two-stage process.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Year Without Pants: What’s Your Conversation Prompt?

Must Hierarchy Always Trump Collaboration?

In the excellent Year Without Pants (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013), Scott Berkun detailed his efforts to direct a team of programmers working for Automattic/Wordpress. This team was distributed around the world and gathered only occasionally. Most of their collaboration was mediated through computer screens and telephone lines. Curiously, email was not a major player. Instead, in-house blogs contained most of the collaborative communication (~75%), along with IRC (Internet Relay Chat), Skype and then e-mail (~1%). Blogs had the advantage of being entirely public (to the other players) and displaying the entire conversation. So potential collaborators could get up to speed as needed by simply reading/re-reading what had been said. And others could ignore the whole thing (which is the way of blogs).

Berkun found the prompt at the top of the collaborative blog was largely ignored—so common it was invisible (much like Twitter’s “What’s happening?”). It started with,

What’s on your mind?

and then

How can Team Social help you?

migrating eventually to:

Hi Scott: Do you know where your pants are?

That changing prompt became a way to wake up the conversation. It also demonstrated the playful nature of the team—a key factor in all Automattic/Wordpress collaborations. The prompt also turned into a good book title.

Berkun’s conversation prompt gives me hope that hierarchy need not trump collaboration. In my most collaborative projects, there was always a sense of fun/playful/silly/ridiculous that settled like a bubble over team meetings. In contrast, my more onerous jobs and projects carried a sense of duty and chain-gang attention to a boss hammering out a beat.

Creating that collaborative environment requires a light touch, a willingness to explore liminal spaces, record results and allow others access to the longer conversation. Creating collaboration also involves attention to conversation that results in replies, rather than monologue that begets numb pseudo-attention.

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston

Let’s Get Liminal: How to be a Co–Laborer/Co-Thinker/Co-Contributor

Show up to explore the space between

My friend helps researchers at his Midwestern university organize their thoughts for publication. He also helps them apply for grants to fund their research—a function many universities are increasingly focused on.

To do this work, my friend has found ways to walk alongside new professors as they form their research interests. By staying beside them over time (years, even), he is able to help identify places where the work can go forward and also begin to locate potential funding sources. That’s when the hard work begins of explaining the research to a funding committee.

This space between—where the research shows particular promise but is still unformed—this is where a conversation can bear fruit. Maybe even the goal itself is starting to take shape, along with possible routes to that desired end. Sometimes it is the conversations surrounding the goal and routes to the goal that open it for exploration.

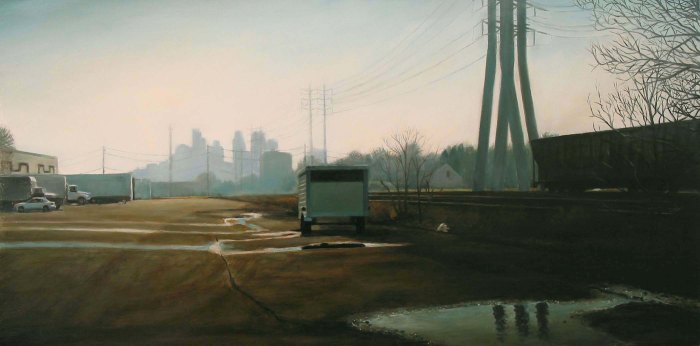

Michael Banning is an observer and painter of liminal spaces—those spaces and places that we typically don’t even see:

I am interested in the liminal spaces found at the edges of the inner city. Amid the trucks, weeds and railroad tracks of those often post-industrial surroundings, one can find compelling views of the distant skyline as well as a sense of peace and quiet uncommon in the urban experience.

–“Parking Lot near Train Tracks,” by Michael Banning, label from James J. Hill House Gallery

See Michael Banning’s work here.

When we are lucky enough to find ourselves talking about these liminal spaces with each other, we might be collaborating in a particularly effective way. Typically we don’t have a clue when we’ve entered such a verbal space. Years later we might identify a conversation that was a turning point. Perhaps the best we can do is to remain open to entertaining each other’s unformed thoughts.

Who knows what might result?

###

Image credit: Kirk Livingston